By Milan Czerny | –

(GlobalVoices.org ) – For Russian soldiers, posting from the battleground was strictly forbidden. Then all of a sudden, it wasn’t

“Yesterday they were here, today it’s us.”

On October 15, the Russian conflict journalist Oleg Blokhin published several videos on social media of himself visiting the former US military base at Manbij, in northern Syria, following the departure of American soldiers. Photos taken by Russian soldiers in similar facilities then began to surface across Russian social media and Telegram channels. Russian TV channels and military-themed pages on VKontakte, a popular Russian social network, quickly relayed the soldiers’ posts in celebration, gloating at the GIs who left Syria in such a hurry.

These scenes stood in sharp contrast to the Russian military’s recent efforts to limit its soldiers’ online activities. Earlier this year, President Vladimir Putin signed a new law prohibiting Russian soldiers from using smartphones and posting photos while on duty. Soldiers are now banned from possessing devices that take pictures and have access to the internet. At the time the law was adopted, the independent media outlet Meduza reported that “large numbers”of soldiers had been jailed and punished for infringing the new regulations. Some of them even faced retroactive charges: Yegor Kruglov spent 15 days behind bars for sending photos of himself to his girlfriend using social media months before the law entered force.

The bill’s authors stressed that it was adopted because “military servicemen are of special interest to the security services of several states, to terrorist and extremist organisations.” However, many believe that the real impetus for the law were revelations by investigative journalists and researchers, such as Bellingcat or the Conflict Intelligence Team, which rely on open-source data, particularly from social media networks. These investigators were able to prove the Russian military’s involvement in Syria thanks to its soldiers’ social media posts and GPS localisation before the Kremlin even officially acknowledged military intervention in the country. Similarly, VICE News’ Simon Ostrovky and researchers from Forensic Architecture were able to gather evidence of the Russian military’s involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine, which Moscow firmly denies. Ostrovsky and his colleagues were also aided by selfies and YouTube videos uploaded by active servicemen.

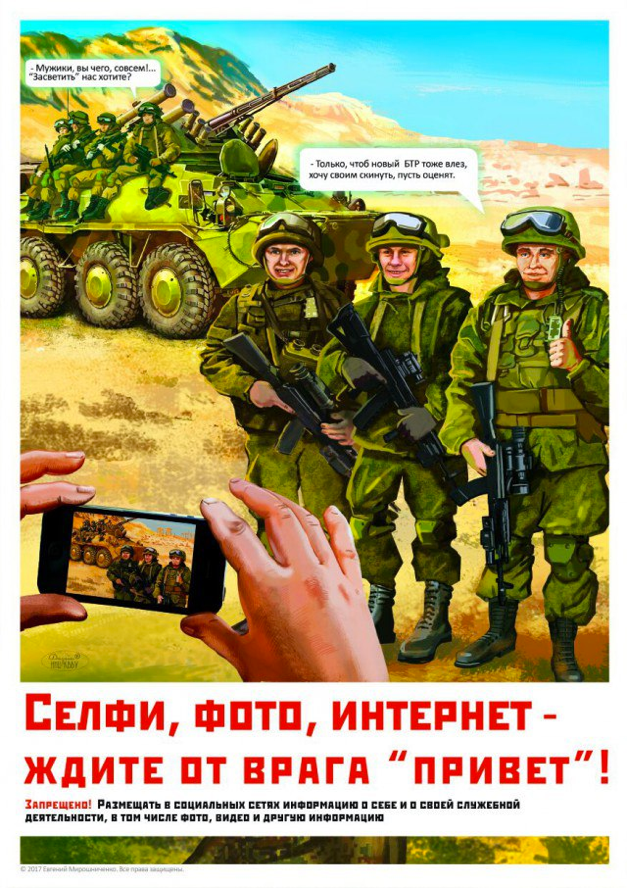

“Selfie, photo, internet: expect a hello from the enemy!” reads this poster. Source: VKontakte/DKulbin (the user’s page has since been closed to the public.)

Despite denials, these revelations clearly irritated Russia’s military leadership. In fact, photos of what appears to be a series of educational posters reminiscent of the Cold War have even appeared online. The posters, which allegedly hang in military facilities, aspire to teach servicemen how to behave online. One poster urges soldiers not to share information on social networking sites. A second poster warns soldiers against using devices which can provide geolocations, which could then be discovered by NATO troops.

Although the authenticity of these posters has not been verified, they appear to be in keeping with a broader push by the Russian military to restrain its soldiers’ social media activity.

This was recently exemplified by a declaration by a former analyst from the Russian Presidential Affairs Department’s Scientific Research Computing Center (GRCC), an agency which produces tools for high-precision online research for sale to state and private actors: “We said there aren’t any Russian soldiers in Syria or the Donbas, but they are there. And so we’re in a race against Bellingcat to geolocate all the posts where some idiot Russian soldier is taking selfies in a trench, posing with his rifle,” one anonymous former GRCC employee told Meduza.

This struggle was toned down when US troops left northern Syria. Empty American bases presented a unique opportunity for a huge symbolic victory. Indeed, the last “deliberate withdrawal” of US troops occurred in 2011 in Iraq; the last time that Russian soldiers set foot in an American base was probably in the aftermath of WWII. Soldiers filmed themselves going through GIs’ personal belongings and diaries, visiting dormitories, checking cans of Coke left behind and responding to messages left on whiteboards.

This reporting appeared to take place in various stages: first, Russian soldiers posted pictures of the bases, and VKontakte accounts reposted videos of Russian vehicles entering Manbij, welcomed by locals waving Syrian flags in the aftermath of the American withdrawal. Simultaneously, journalists following Russian mercenaries, such as Oleg Blokhin or the Abkhazian news agency Anna-News — which claims to “fight the western brainwashing machine” — staged their own visits to the US bases in a more elaborate manner, so as to channel the information in the desired way. Finally, larger Russian TV channels such RT filmed their own visitsto the abandoned facilities.

Social media allowed the Russian government to instantly and forcefully communicate its presence and “success” in Syria. The erosion of the American role in the Middle East was staged live, and despite new information security measures, the Russian military is willing to weaponise its soldiers’ social media posts when it is convenient to do so.

In the short term, it seems that the rapid dissemination of these posts advanced Russia’s interests. VKontakte videos found their way to a Western audience on Twitter, polarising discussions and fuelling heated criticism of Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw US troops from northern Syria and give Turkey and Russia a green light to extend their territorial reach. Moreover, these posts probably harmed the morale of Western troops, as the live broadcast of the base’s “takeover” was a cheap way for the Russian government to portray itself as the only superpower left in the region.

However, in the long term, the widespread use of such social media posts, whether by active servicemen or by mercenaries, might be detrimental to Russia’s interests, undermining the spirit of the legislation passed to ban the use of social media on the battlefield. It appears as though Russian soldiers have had a hard time restraining themselves from boasting in front of tanks or posing in full military gear despite the implementation of the law. It could now be difficult to close this Pandora’s Box in the coming months.

Finally, the strategy of mocking Western states by staging videos around sensitive information has recently backfired. In September 2018, the Kremlin-sponsored RT television channel held an interview with two men belonging to the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU), the Russian military’s overseas intelligence agency, who had been accused of poisoning Sergey Skripal in Salisbury, Great Britain, earlier that year. In response to British allegations that they had carried out an assassination attempt ordered by Moscow, the two men claimed that they were sports nutritionists on holiday in the UK. The footage proved to be very valuable to Bellingcat’s attempts to establish the real identity of the two men; as a result, photos were discovered of the two men attending the wedding of the daughter of Major General Andrey Averyanov, a GRU commander.

This shows that, for any military, playing with sensitive information for easy PR points can be a dangerous game. Although American troops may have felt humiliated by Russian soldiers’ posts of their former base at Manbij, it is likely that, in the long run, open-source investigations team will have plenty more data to analyse.

Milan Czerny is a student of International Relations at King’s College London. I focus on Russia’s relations with the Middle-East, notably with Israel, and on regulations of the Runet.

Via GlobalVoices.org

——

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

CBS News: “Russian troops take command of U.S. airbase in northern Syria”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved