By Mieczysław P. Boduszyński | –

In all the hand-wringing that critics and commentators have done since President Donald Trump announced the withdrawal of U.S. troops from northern Syria, one of the common refrains emphasizes the breach of trust between Washington and its Kurdish militia partners.

Some scholars of international relations put little stock in trust. Countries are selfish, after all.

Others see trust in impersonal terms, embedded in the rules, norms, institutions and alliances that bind countries to each other.

It turns out, though, that trust does matter in international relations. And in the Middle East, trust is often seen in personal terms.

For the American personnel who worked, ate and lived with the Syrian Kurds, trust-building was also a deeply personal experience. Trust underpinned the crucial intelligence cooperation between the U.S. and its Kurdish partners. That cooperation helped plan and execute the raid that led to the capture killing of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

As one former American special operator has written, “Trust is a powerful commodity that has saved many lives in shadowy battlefields across the Middle East. But it takes a long time to build and can be gone in an instant.”

By contrast, mistrust, even if it is based on perception alone, can linger for decades, thwarting Washington’s foreign policy goals.

Defeating the Islamic State

I observed the long-term consequences of broken trust next door to Syria, in Iraq.

I served as a U.S. diplomat in the southern Iraqi city of Basrah during 2015 and 2016, the height of the war against the Islamic State group, also known as IS.

At the time, after years of sectarian strife, dishonest governments and their broken promises, Iraqis seemed united around the common purpose of defeating IS. The corrupt and sectarian regime of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki had been ousted. And the U.S. was leading an international coalition to help the Iraqi government in the fight against IS, providing hundreds of millions of dollars in humanitarian assistance.

You might think that a war that the U.S. was fighting on behalf of the Iraqi people, a war that was truly an existential one for the majority Iraqi Shia, would have produced at least some goodwill toward the United States.

Instead, when I arrived in Basrah in 2015, I discovered that many Iraqis, including the majority Shia Muslim population among whom I lived, believed that the United States was somehow in cahoots with the Islamic State.

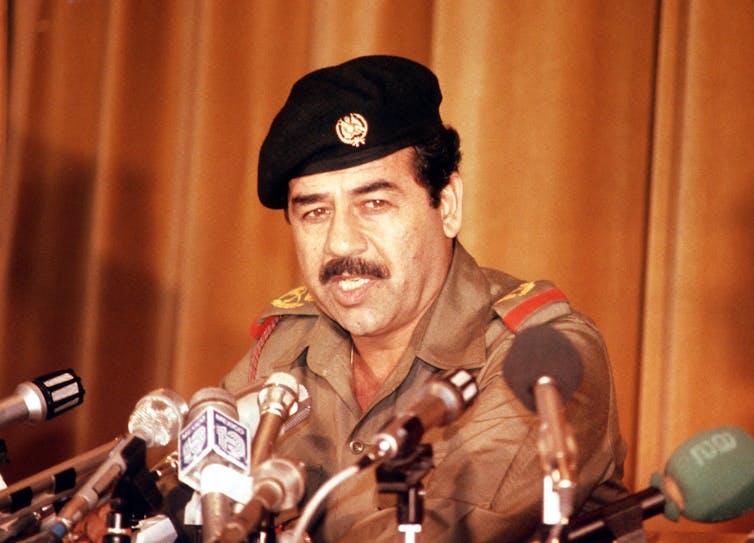

AP photo

Mistrust for decades

The Middle East is rife with conspiracy theories. But this one was particularly jarring given that the United States was then engaged in a costly and very public effort to defeat the Islamic State, a terrorist group which declared the Shia apostates and said they must be killed.

Over time, I began to understand the roots of these attitudes. Disinformation and propaganda, especially from Iran, fueled them to some extent.

But there were deeper issues at play.

“The United States defeated Saddam’s armies in a matter of weeks,” incredulous Iraqis I met would say to me. “So how is it that you can’t defeat a ragtag army of jihadists in two years?”

Iranian disinformation campaigns blaming the U.S. for the Islamic State were effective because of a deep gulf of mistrust between the U.S. and Iraqis, which led to widespread cynicism among ordinary Iraqis about U.S. motives.

The origins of this mistrust go back decades, from tacit U.S. support for Saddam Hussein in the 1980s, when Washington turned a blind eye to the dictatorship’s atrocities against Iraqi Kurds.

The lack of trust helps explain why the U.S. had such a hard time stabilizing Iraq after 2003, despite toppling a feared despot and despite investing billions of dollars in the country.

Roots in betrayal

Iraqi Shia are the largest Muslim sect in the country, but have less political power than Sunni Muslims. The Shia in particular have painful memories of an event that they see as a massive breach of trust between them and the U.S.

In 1991, encouraged by then-President George H.W. Bush, the Shia rose up against Saddam, only to be abandoned by the U.S.

Tens of thousands of Iraqi Shia were slaughtered.

I visited a memorial to the victims of Saddam’s suppression of the uprising, where I saw a leaflet displayed that was dropped by U.S. and coalition aircraft calling on Iraqi soldiers and civilians to “fill the streets and alleys and bring down Saddam Hussein and his aides.”

“We thought this meant that the Americans would help us,” my guide at the museum told me.

AP/Andrew Harnik

Many Iraqis I met also recalled the devastating 1990s sanctions on their country that were championed by the United States. Others talked of Washington’s failure to stabilize the country after 2003. Then there was the perception that the Obama administration came late to the war against the Islamic State.

Other Iraqis I met – young ones – told me of their resentment at U.S. support for a political class in Baghdad that is seen as deeply corrupt. Some of them are no doubt protesting in the streets and squares of Iraqi cities today.

I attended lots of meetings with Iraqi Sunni tribal leaders in the south. They saw the Obama administration’s 2011 withdrawal of U.S. troops and general disengagement from Iraq as a betrayal of trust. They saw it as handing over Iraq to Iranian influence, which they fear.

Ultimately, Iraqis did not see the U.S. as a credible, consistent or committed partner. Some turned to Iran for assistance, while turning against the United States. Perhaps it is no surprise that polls taken at the time I worked in Basrah showed that Iraqis saw Iran and Russia as more favorable security partners.

Can’t escape the past

Iraq is by no means a perfect analogy for the shattered trust between Washington and its Syrian Kurdish allies. Yet the the Iraqi experience shows that distrust of the United States has deep roots in past U.S. actions.

In Syria, too, the U.S. has left a legacy of mistrust since 2011, from Obama’s failure to follow through on his call for Assad to step down, to his failure to impose meaningful costs on the Syrian regime for its use of chemical weapons. Trump’s withdrawal is just one episode in a longer story.

Despite breaches of trust, Iraqis continued to need U.S. support. But that need paired with a lack of trust makes things difficult for American diplomats in Iraq. For me, it was often overwhelming to be at the receiving end of the immense disappointment, frustration and more rarely, hope, that the Iraqis have in the United States.

The Syrian Kurds, like the Iraqis, will still need the United States and continue to work with Washington. But the breach of trust will complicate cooperation, as it did in Iraq.

Not everything that Iraqis blame the United States for is fair. And it would be impossible for even the best-crafted U.S. policies to satisfy all of Iraq’s diverse people.

At times I tried to remind my unfailingly hospitable Iraqi interlocutors, especially those in the government, to be a bit more introspective about their own failings and responsibility for Iraq’s post-Saddam ills. I tried to remind them that the United States invested a lot in Iraq, with limited results.

In the end, the credibility of the message was undercut by a lack of trust in the messenger.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Mieczysław P. Boduszyński, Assistant Professor of Politics, Pomona College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

—-

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

The Straits Times: “Iraq protests see four more killed, scores wounded”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved