Eau Clare, Wi. (Special to Informed Comment) – Much has been speculated and written about the possibility, trajectory, and the likely consequences of a war between the United States and Iran. In case of a wider war that may threaten the survival of the Islamic Republic, Iranian leadership will inevitably push for an all-out war that will drag Saudi Arabia and Israel into the fore. In the worse scenario, Iran will fall into disarray and instability and with a possibility of military rule under the remnants of the Iranian military and the Revolutionary Guards Corps, the IRGC. The consequences of such a war will also impact Iran’s immediate and far neighbors, as far away as Israel, Lebanon, and Jordan.

With essentially weak and ineffective governments in Kabul, Tehran, Baghdad, and Damascus, terrorism will reign rampant and more violent than before, with inevitable spillover into Europe, and Northern America. Millions of new refugees will push their way Westward toward Europe, destabilizing Turkey along the way. The United States, in turn, will be bogged down in a state of hostility for years to come and with trillions of dollars wasted. The US presence in the region will be extremely costly, hastening its hegemonic decline. Moreover, the inevitable rise in the price of oil and natural gas will have a wider global impact: It will weaken European economies’ already fragile state and will slow down the economies of China and India as major importers of oil. In the long term, Iran will further distance itself from the West and will accelerate its nuclear program. The consensus, therefore, should be that such a war of choice must be inconceivable.

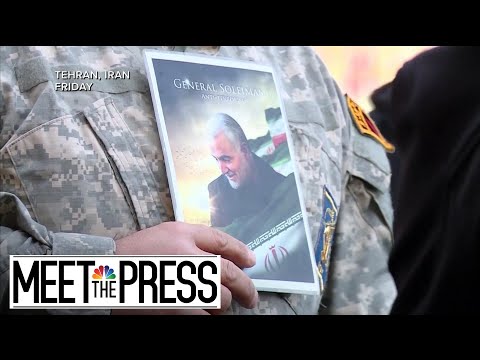

President Donald Trump so far remains the only president in recent memory to not have led the U.S. in an invasion of a foreign land under some pretext. President Trump’s preoccupation with domestic politics and a brazen confrontation with US economic partners, be it China, Canada, Mexico, or the European Union, leaves little incentives for yet another US military involvement in the Middle East. This is particularly true for a president whose rise to power and hopes for a second term owes something to the promise of ‘No Endless Wars.’ The question, therefore, remains as to how the U.S. should deal with Iran and its, so-called, ‘mischiefs?’ Iran has been accused of sponsoring terrorism, pursuing nuclear weapons, meddling into affairs of other countries, and suppressing its citizens in violation of basic human rights. Despite such highly exaggerated and misconstrued claims, the rise of Iran as a regional power is positive for the U.S. long term interest in the region. The hastened assassination of the second most powerful and popular man in Iran, the head of Iran’s revolutionary guard’s Quds force, Qassim Soleimani, and his Iraqi associates, can only telltale, at best, of a badly miscalculated advice or, at worst, an ideologically driven move colored with personal score boarding.

The rise in Iranian power can be funneled toward regional peace, stability, and cooperation; Iran’s wider regional participation can serve the cause of Persian Gulf security and reduce U.S. military presence in the region in line with a ‘Trumpian America First’ slogan. Given the increasing Russian footprint in the region and fast-paced regional development, a U.S.-Iranian rapprochement can be instrumental in serving the cause of peace and cooperation and prosperity in the Persian Gulf region and beyond. For a successful rapprochement between the United States and Iran, however, the United States needs to remain true to the fundamental principles of Realpolitik in dealing with Iran in pursuit of its longer-term national interest. Such an approach would require the U.S. reverting to its cold war policy of political realism that relied on regional

cooperation in countering threats to the region. The neoliberal and neoconservative driven U.S. Mideast policies have led to wars, instability, and uncertainties and at the expense of its national interest. To this end, several factors are vital to consider.

First, it is paramount for the United States to acknowledge Iran as a ‘pivotal state’ with legitimate interests in regional politics. Iran shares national characteristics with countries designated as ‘pivotal states;’ countries with important national characteristics, pivotal in the management of regional affairs, e.g. Mexico, Brazil, Algeria, Egypt, South Africa, Turkey, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Pivotal states share certain characteristics in common, including, large population, important geographical location, economic potential, and physical size, and their fate is vital to the United States’ overall global policy. What really defines a pivotal state is its capacity to affect regional and international stability. A pivotal state is so important regionally that its collapse would spell transboundary mayhem: migration, communal violence, pollution, disease, and so on. A pivotal state’s steady economic progress and stability, on the other hand, would bolster its region’s economic vitality and political soundness and benefit American trade and investment (p. 37).

Iran’s cultural heritage and history, human capital and natural resources and geostrategic location stand out in West Asia and as a corridor to Europe, the Persian Gulf, and Africa. Iran is a country of 83.75 million and has the longest shoreline in the Persian Gulf and the sea of Oman. It sits on 7% of world minerals, including copper, iron ore, uranium, gold, and zinc, and lead, and is ranked among 15 mineral-rich countries. Iran’s proven oil reserves are the 4th largest in the world and its natural gas’ rank second (perhaps even first after reports of some new discoveries) in the world, just behind Russia. Iran’s economy has been under strain since the revolution and yet it is ranked the 18th largest in the world, with a GDP (PPP) of more than $1,627 trillion dollars in 2019, and a per capita of $19,541, 1.14% of the world economy.

According to the United Nations, Iran’s Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2017 was 0.798— which put the country in the high human development category— positioning it at 60 out of 189 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2017, Iran’s HDI value increased from 0.577 to 0.798, an increase of 38.3 percent: Iran’s life expectancy at birth increased by 12.4 years, mean years of schooling increased by 5.6 years and expected years of schooling increased by 5.7 years, and its GNI per capita increased by about 67.5 percent between 1990 and 2017. Iran has slowly moved away from a rentier state, dependent on the export of crude oil into a welfare state with a diversified economy. Iran’s military also is ranked 14 in the world in 2019 by Global firepower or as the 13th most powerful military in 2018 by the

Second, the United States must accept that Iran has legitimate national concerns over its domestic and regional security and developmental issues, and not be viewed simply as a pariah state. Iran shares a long border with Afghanistan and is vulnerable to the presence of ‘hostile’ US and NATO troops so close to its border. It has also lost thousands of its border guards and soldiers in countering narcotrafficking, terrorism, human trafficking, and smuggling. While Iran had nothing to do with the events that inspired the September 11, 2001 attacks on America, it was labeled as a member of the ‘axis of evil’ by the neoconservative-dominated administration of President G W. Bush and it has paid dearly for the U.S. declared war on terrorism.

Iran has experienced the sociopolitical and economic turmoil of the 1978-79 revolution, terrorism and insurgency since the1980s, a devastating and costly war with the invading Iraqi army, two major U.S. invasions of its neighboring Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) with consequent instability and flood of refugees into its territory, forty years of uninterrupted UN and/or US and European economic sanctions and political pressure, and the hostility of much of the Arab world, spearheaded by Saudi Arabia. This is while the government has since the revolution tried building the foundations of a Shi’a-based Islamic Republic by a process of ‘trial and error,’ resulting in ideological and political factionalism, mismanagement of the economy, and political corruption. Iran’s experimentation with Islamic Republicanism has raised many questions and concerns about the nature of the state-society relations. The future shape and nature of democracy in modern Iran must be determined by the country’s historical, cultural, and modern indigenous sociopolitical and economic experiences.

Whether the experimentation with Islamic Republicanism can succeed or not, it is a matter for the Iranian populace to decide. Regardless, Iran has gone through drastic national changes, making it a much more dynamic and exuberant country with tremendous potential for national development. Structural changes in Iran since the revolution has led to a dynamic and inquisitive population and society who has proven persistent in its quest for more social freedoms and good governance. The population of the country is relatively young, very educated and technologically savvy. More importantly, the populace and civil society in Iran today gravitate towards the West in intellectualism and societal needs and expectations. The United States’ conflict with the government’s foreign policy orientation must not isolate and punish its populace. In the end, whether Iran’s future embraces an ‘Islami constitutionalism’ or liberal constitutionalism, or a different political makeup, the post-revolution generation has embraced causes of national development and peace and regional cooperation and integration. A policy of engagement with Iran is much more efficient and promising in the long run. Iran’s potential for rapid growth and development is very bright, should its economy and polity be integrated into the regional political economy.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II coined in 2004 the phrase ‘Shia crescent’ that supposedly implied a ‘Shi’a unity’ that went from Damascus to Tehran, passing through Baghdad. The Shia crescent tag was an unfortunate statement, presuming the root of anxieties, worries, and conflicts in the region is sectarian and not political. As Ian Black of BBC commented, the narrative simply was simplistic, “smoothing over local factors of ethnicity and nationalism to provide a single, overarching explanation. In a region where political discourse is often coded, it was highly unusual to hear such blunt language.” Iran’s support for its ‘proxy’ allies is a calculated policy to empower forces beyond its borders that are ideologically and/or politically are potential allies. Iran does not control or direct its ‘proxy’ forces: Tehran has never been interested in cultivating a network of completely dependent proxies. Instead, it has tried to help these groups become more self-sufficient by allowing them to integrate into their countries’ political processes and economic activities and helping them build their own defense industries—including by giving them the capability to build weapons and military equipment in their own countries rather than rely on Iran supplying them. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/16/irans-proxies-hezbollah-houthis-trump-maximum-pressure/ Lebanon’s Hezbollah (Party of God) and Iraq’s Hash al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilization Forces, PMF) are primary examples of such groups.

Iranian leadership believes the US-back attempt at regime change in Syria was a prelude to the downgrading and the destruction of Lebanese Hezbollah and military action against Iran itself. That is, regime change in Iraq, Libya, and then in Syria would sniff out Iran’s regional influence, making it a much softer military target. The United States is thus viewed as hostile and interventionist, with intention to topple the regime, proven by not only its historical role in the 1953 coup d’état of the legal Iranian government of Muhammad Mosaddeq, but by the vehement rejection of the Islamic Revolution, disregard for Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq War, the 1988 shooting down of its passenger plane, the imposition of decades-long sanctions, freezing of Iranian financial assets, rejection of Iranian civilian nuclear progress for clean energy, withdrawal from the UNSC sponsored nuclear agreement, JCPOA, repeated threats to attack Iran, and now the assassination of the head of Iran’s revolutionary guard’s Quds force, Qassim Soleimani. Iran has for most of the past forty years has been a subject of repeated US and Israeli threats of military attack and regime change, with even hints of Israeli nuclear strike against Tehran!

Third, U.S. Mideast policy since the advent of September 11, 2001, terrorist attack has been dominated by the hawkish neoconservative ideologues of the GW Bush years (2001-08); the interventionist neoliberalism of the Clinton (1992-2000) and the Obama (2008-2016) years, and now the haphazard policy of ‘neomercantilism’ of Donald Trump presidency. In spite of its declared policy of a ‘war on terror,’ U.S. actions have contributed to the spread of terrorism across the region and onto Europe, the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, or the Daesh), continuing support of Arab authoritarian rulers despite their horrendous human rights records, and emboldening Israeli political rights to avoid any serious attempt at resolving, not merely managing, the Palestinian issue. Billions of dollars have been spent in the US invasion of Afghanistan (war of necessity) and Iraq (war of choice). The Arab Spring movements also prompted US-led NATO operation in Libya (another war of choice but under the guise of neoliberal idealism of ‘Responsibility to Protect’) and in Syria (another war of choice instigated by U.S. allies’ proponents of regime change in Syria, namely Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Israel). The United States’ support for the Saudi Arabia-led supposed coalition to intervene in Yemen’s civil war since 2015 has meant the perpetuation of Yemeni conflict and unimaginable sufferings for its people.

The changing dynamics of regional politics demands a more pragmatic U.S. policy. Instead, U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq opened the way for increased Iranian influence in both countries. Iran has used its Shi’a doctrine’s soft power to recruit Afghan and Iraqi fighters to join the Syrian forces fighting radical foreign-supported militants. Furthermore, the US and its regional allies’ intervention in Syria only incited Iran’s fear of a US-backed attempt at regime change after Syria. The power vacuum created by the US and its Arab allies’ policy of regime change compelled the Assad regime to ask for a more entrenched Iranian participation. Iran’s involvement in Syria would have remained limited to military and economic cooperation, short of its current (and future) military presence and foreign-fighters recruitment and sponsorship. Iran, however, is not the only external military force in Syria, as foreign fighters from Europe, Africa, Central Asia, and the Arab world have been fighting on opposite sides in the Syrian war theatre.

Some observers consider the Islamic Republic’s regional policies as diametrically opposed to the United States’. There are, however, some shared regional issues that are of mutual interest requiring Iran’s cooperation to secure the Persian Gulf and a more ‘tranquil’ U.S. presence in the region. Among other issues of mutual concerns are drug and human trafficking, combating terrorism, stability and national integrity of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, and the end of the war in Yemen. The U.S. can help strengthen ties among regional actors, including Iran, in settling their differences in the service of peace, prosperity, and shared interest, while taking confidence-building measures to ease tensions with Iran. The United States’ return to the nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA, can lead to further negotiations over Iran’s role as an instigator of regional cooperation and development. A policy of engagement is far more fruitful than the current policy of mistrust, punishment, and isolation.

The assassination of Qassim Soleimani has seriously undermined the voice of reason on both sides, with threats and counter-threats coming out of Tehran and Washington. President Trump’s administration almost certainly consulted the Israeli government before the strike on Soleimani and his Iraqi associates, and without any Iraqi input into the matter. Such hasten actions defy thoughtful and strategic principles of realpolitik and only serve voices of radicalism in both administrations in Tehran and Washington.

Conclusion

Iran’s foreign policy doctrine and behavior is fundamentally defensive in nature, reflecting its lesser military capabilities and the state insecurity in the face of persistent external hostility and threats at regime change. Iran utilizes anti-Americanism and Islamic revolutionary rhetoric as ‘soft power’ to mobilize transnational popular support and militia groups in the neighboring countries, where the U.S. and Israel are perceived as enemies and the source of instability and discord. The Islamic Republic remains steadfast in its ‘Neither East, Nor West’ slogan, instigating national self-reliance and development while maintaining an independent foreign policy. Iran’s closer ties with China and Russia is as much a strategy of necessity as it is a strategic choice, given the U.S.-led hostility of the West. Iran has had a long historical tie with Europe and still can benefit from Western technical and technological expertise. A policy of isolation is only bound to further push Iran into the bosom of Russia and China, with long term economic and political consequences for the Persian Gulf and wider regional security and commercial activities.

Iran’s involvement in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen is defensive against serious threats from radical Salafi militants and aims to extend its strategic depth to further (along with the help of Hezbollah in Lebanon) deter them and to counter an American or Israeli preemptive attacks on its nuclear and strategic assets without fear of reprisal. Iran has legitimate national and regional interests. The removal of serious external threats can leave wider room for diplomacy and rapprochement with the West and the United States. The inclusion of Iran in any Persian Gulf security arrangement is indispensable and that itself is contingent upon recognizing Iran as a pivotal state whose regional role can be instrumental in peace and security that can also safeguard a better, more balanced U.S. Mideastern policy.

—–

Related video added by Informed Comment:

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved