Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was a worldwide publishing phenomenon from about 1880 until the 1970s, and is still beloved by many readers.

Rubaiyat is actually a plural, meaning “quatrains.” The singular would be ruba’i, with a long a and “a” long “i.” The word is from the Arabic root for “four,” because the poem consists in Persian of four hemistiches or half-lines.

A celebrated example of the FitzGerald ruba’i is his No. 11:

Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough,

A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse – and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness –

And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

I can’t tell you how many nervous 20th century suitors showed up to a first date with this poem clutched to their breasts.

One complaint I have about FitzGerald is that he used a high diction and some archaicisms (like “enow” for enough) to translate poetry that in the original is most often simple in its vocabulary and earthy in its sentiments. His 35 is an example:

I think the Vessel, that with fugitive

Articulation answer’d, once did live,

And merry-make; and the cold Lip I kiss’d

How many Kisses might it take – and give !

Order from

or Nicola’s Books in Ann Arbor, who will ship it to you

or Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, who will ship it to you

or Barnes and Noble, who will ship or do curbside delivery.

or Amazon

Reviews:

“’To read Juan Cole’s deft, plain-spoken translation of the Rubáiyát

is to find companionship, to rejoin a thousand-year human

conversation about how to endure, enjoy, and find a fleeting beauty

in everlastingly dire times. The lucid, cogent and mind-opening

Epilogue is a kind of grace, a gift freely given, from one of our

most astonishing and generous intellects.’”

– Michael Chabon, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of Moonglow (2017)

“’Omar Khayyam is a Persian treasure and Juan Cole’s new

translation brings him anew to Western audiences who

for centuries have been both delighted and educated by this

medieval sage! Reading The Rubáiyát is a thrill – you feel the

echoes of the 12th century seamlessly into our 21st, as this is

a holy book of wisdom and magic. In another perilous era for

Iranians, it’s wonderful to see this enchanting volume make

its way through the world yet again!’”

– Porochista Khakpour, novelist, essayist and author of Brown Album (2020)

Here is how I approach this poetry, though this one isn’t in the forthcoming book:

At dawn, a shout awoke us in that watering hole . . .

You crazed carousing drunk!

Get up and grab that bottle: Let’s finish what we started

before fate starts to finish us.

(- Whinfield No. 1).

In Persian literature, rubaiyat emerged in the 900s, two centuries after the Arab Muslim conquest of Zoroastrian, Persian-speaking Iran. In Persian, each ruba’i is a stand-alone poem, rather like the Japanese haiku. As with the haiku, the last line in a ruba’i often contains a twist or a surprise, which casts the previous lines in a different light.

FitzGerald himself attempted to link several four-line stanzas thematically, as did Robert Frost. But this is an English-language custom, perhaps an attempt to make the rubaiyat more like sonnets. There is no reason for English-language poets, however, to be obliged to link stanzas, especially since there is no such custom in the original Persian.

The Persian rhyme scheme for rubaiyat is most commonly aaba, which FitzGerald brought into the English (aaaa is also a possibility, and occurs in a few of the FitzGerald stanzas). FitzGerald used iambic pentameter as his meter rather than trying to imitate the Persian original.

FitzGerald’s form of the Rubaiyat had an immediate impact on other poets. The pre-Raphaelite Algernon Swinburne (1837-1909) composed his “Laus Veneris” (“In Praise of Venus”) after reading it. In that poem, published in 1866, he wrote of the love of a medieval knight, Tanhauser:

There is a feverish famine in my veins;

Below her bosom where a crushed grape stains

The white and blue, there my lips caught and clove

An hour since, and what mark of me remains?

O dare not touch her, lest the kiss

Leave my lips charred. Yea, Lord, a little bliss,

Brief bitter bliss, one hath for a great sin;

Nathless thou knowest how sweet a thing it is.

These stanzas are Rubaiyat with an aaba rhyme scheme, echoing the themes of passionate love often found in the Persian originals.

In my view, there is no intrinsic reason for which an English ruba’i should need to rhyme or have meter. A free verse or blank verse quatrain would do, as long as it treated Omarian themes.

Poet Lawrence Joseph wrote rubaiyat to interrogate the horrors of America’s post-9/11 forever wars:

- “Rubaiyat

The holes burned in the night.

Holes you can look through and see

the stump of a leg, a bloody

bandage, flies on the gauze; a pulled-up

satellite image of a major

military target, a 3-D journey

into a landscape of hills and valleys . . .

All of it from real-world data.”

Rubaiyat were produced on many subjects, including on Sufi mysticism and on themes of romantic love.

The Rubaiyat that were gathered under the name of the Seljukid astronomer Omar Khayyam by the Qara Qoyunlu scribe Mahmud Yerbudaki in 1460, however had a few distinct themes. They regretted that life is fleeting. They expressed skepticism about the afterlife and the surety of heaven and hell. Their response to this realization, that death is near and could well be final is to advise the reader to find someone to love, and to enjoy some good wine and to make music. There is an impatience with abstract philosophy and with astrology (those planets you think determine your fate are a thousand times more helpless than you are). There is also a delight in nature, and in its renewal at spring, and in the beauty of flowers, trees and birds, that is, again, reminiscent of the haiku. The poetry is not exactly libertine, since it advises readers against being hurtful to people.

FitzGerald more riffed on the originals than he translated them, but he was most often faithful to their spirit. His no. 7 is a good example:

Come, fill the Cup, and in the Fire of Spring

The Winter Garment of Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a little way

To fly – and Lo! the Bird is on the Wing.

This poem shares many of the typical themes of the Omarian rubaiyat. It advises filling a cup with wine and giving up on previous moments of repentance (drinking wine is frowned on in strict Muslim society). The reason given is that time is fleeting and life is nearing its end. The poetry does not advise drowning existential anxiety in a drunken stupor but rather the quest for secular transcendence, finding meaning in this life since there likely isn’t any other.

FitzGerald’s rendering of the Rubaiyat and its wild popularity led other poets to take up the form.

Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” is one celebrated example:

- “Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.”

Frost kept the Persian rhyme scheme of aaba, and cleverly linked the stanza by using the ‘b’ rhyme in one stanza as the ‘a’ rhyme in the next (this is called a “chain rhyme.”) The final stanza is aaaa. For meter, he used iambic tetrameter rather than FitzGerald’s iambic pentameter.

Thematically, Frost evokes the existential bleakness of the original. The traveler is caught “Between the woods and frozen lake/ The darkest evening of the year.” His advice of persistence is also faithful to the Persian originals, though his traveler does not seem to have a flask of whiskey with him to get through the snowy journey.

FitzGerald’s no. 14 had similar themes:

- “The Worldly Hope men set their Hearts upon

Turns Ashes – or it prospers; and anon,

Like Snow upon the Desert’s dusty Face

Lighting a little Hour or two – is gone.”

The celebrated translator of Rumi, Coleman Barks, has shown that the Persian Rubaiyat can also be rendered into powerful English poetry in free verse:

- “I would love to kiss you.

The price of kissing is your life.

Now my loving is running toward my life shouting,

What a bargain, let’s buy it.”

I would argue that Rubaiyat are defined more by substance than by form. As the examples by Joseph and Barks above show, English free verse quatrains can be a vivid vehicle for expressing the existential doubts and weariness, and the transcendence, found in the originals.

Rubaiyat are right-sized for Twitter, so if anyone wants to share one of their own with me, just tweet to @jricole

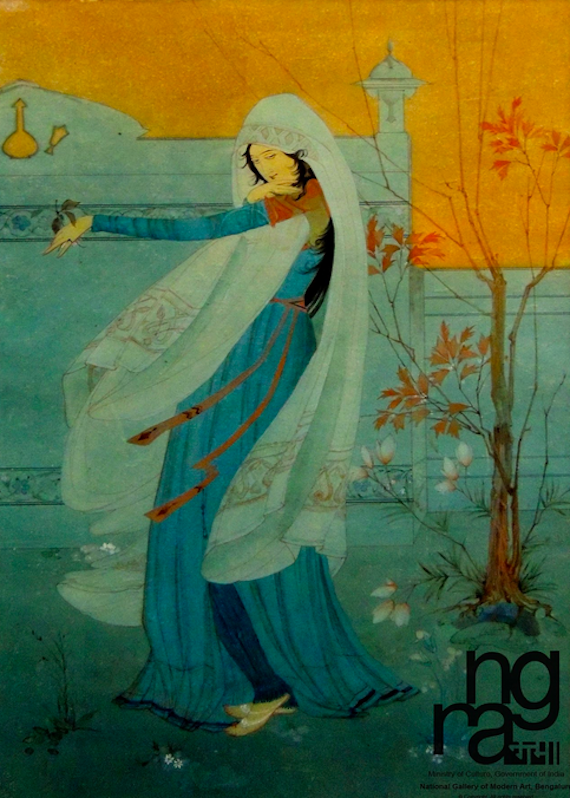

Featured Illustration: “Omar Khayyam,” by Abdur Rahman Chughtai, National Gallery of Modern Art, Bengaluru.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved