By Brian Glyn Williams and Javed Rezayee | –

Williams, Boston/Bamiyan. On November 13th yet another suicide bombing shredded the lives of people across the globe in a land whose seemingly endless conflict has once again been forgotten by many, if not most Americans. But, as devastating as that blast that took the lives of twelve people and wounded twenty others in Kabul was, it pales in comparison to a far worse atrocity that took place three months earlier. Even by Afghan standards the August 17th slaughter of 80 people by an ISIS suicide bomber targeting Hazara Mongol “apostates” who were celebrating a wedding was sickening. The infiltrator detonated his powerful bomb in the middle of a packed wedding hall in front of the band and, in a horrible instant, turned a scene of joyful celebration into a bloodbath. In a tragic reversal of the maxim that art imitates life, the bloodshed surpassed the butchering of Stark bannermen in the “Red Wedding” episode in the popular Game of Thrones series in its wanton cruelty.

The relentless ISIS targeting of Hazara Shiites by suicide bombers reminded me of my encounters I had with this ethnic group while doing counter-terrorism work for the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Center in Afghanistan in 2007. I had been tasked with tracking the movement of suicide bombers, like the one who infiltrated the wedding, in the southeastern lands of the ethnic Afghans (often known as Pashtuns, the country’s dominant, Indo-European Aryan group who also make up the bulk of Taliban fighters) when I first encountered Hazara highlanders. The Hazaras, a minority that claims descent from Genghis Khan’s world-conquering horsemen who live primarily in the remote fastness of Afghanistan’s central Hindu Kush mountains, played an outsized role in the Afghan National Army and US military operations for good reason. As long-repressed members of the Shiite sect, who have seen their villages torched and people massacred by the Taliban from the dominant Sunni sect, they were fighting an enemy that considered them to be “Godless heretics” worthy only of butchering.

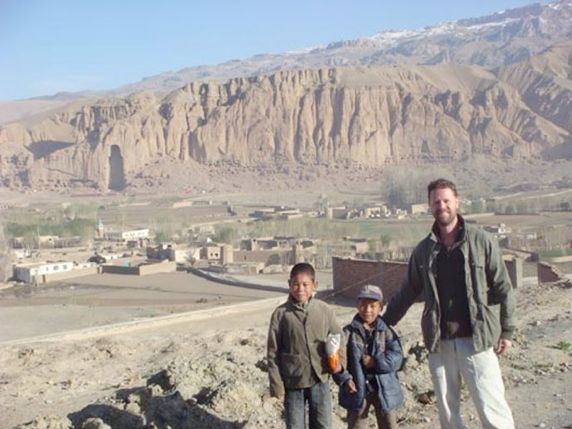

During the course of my extensive fieldwork in the Taliban-infested Pashtun lands, where I came to admire the courage of the Hazara soldiers serving alongside US troops, I became overwhelmed by the mindless and often random horror of the war. After arriving at the scene of particularly gruesome suicide bombing of civilian men, women, and children in the eastern town of Gardez, I got permission to leave the killing behind for a while and decompress in the sheltering peaks of the Hindu Kush. There, in the snowy mountain-ringed Hazara capital of Bamiyan, I found panagah, sanctuary, and a welcoming people governed by Afghanistan’s only female governor. In those terraced, clay-walled mountain villages clinging to the side of steep, misty valleys, I also found widespread gratitude to the Americans for their role in liberating the Hazaras’ lands. Theirs was a relatively peaceful world that was so far removed from the war ravaging the hot Pashtun lowlands to the southeast that I imagined it to be an Afghan Shangri La. While there were signs of the Taliban’s cruel rule over this people, such as the crumbled ruins of the magnificent 6th century Buddhas of Bamiyan that had been blown up by the Taliban iconoclasts as “heathen idols” in 2000, this mountainous realm was relatively peaceful, welcoming and safe.

Williams in the Hazaras’ legendary Bamiyan Vale with the niche carved in the mountain behind him where one of the ancient 5th century Buddha carvings stood before being blown up by the Taliban as “heathen idols.”

My fondest memories are of a class of Hazara school children who came out of their simple school to sing for me (including one girl who proudly showed me a cherished item that could have gotten her killed in the Taliban-dominated southern plains where women are denied the right to write and read, her first pencil) and of singing women working in the fields wearing bright red headscarves, instead of the burqa head and body-covering veil that was enforced in the more conservative Pashtun lowlands. Other sights that were seared in my conscious included those of young men riding proudly on their shaggy steppe ponies with hunting hawks on their arms, men lined up for prayer in the fields at sunset facing Mecca, and laughing children following me everywhere trying to see what the American in their lands was up to. I also recall the horse-mounted Hazaras’ rough and tumble version of polo known as buzkashi and evenings spent with my hosts dining on mouthwatering Kabuli rice and kabobs and listening to ancient epics.

Afghan school girls photographed by Williams on his journeys in the mountains.

The August wedding slaughter of so many of this welcoming people who have faced centuries of conquest, slavery, slaughter, and repression at the hands of the ruling Afghan-Pashtuns brought back painful memories of my fieldwork as well as warm memories of the mountain refuge I found among the Hazaras of Afghanistan. I wanted my fellow countrymen to care more about this people’s suffering and wondered how Americans would react if 80 people were slaughtered in a wedding celebration here. As a Bostonian, who remembers the outpouring of grief across America following the killing of three people in the Boston Marathon bombing, the Hazara wedding massacre reminded me of the sympathy and support we received after that tragedy. I wanted the same concern and sympathy for this pro-American people who were suffering from savage attacks by the Taliban and a relentless bombing campaign by ISIS.

In this sentiment I was thankfully not alone for in Boston I was blessed to have a dear friend who knew the epic land of Afghanistan far better than me and was as frustrated by the widespread American disconnect from the Hazaras,’ and all Afghans,’ suffering as I was. He too was anguished by the images of grief, including unbearably sad photos of the slain sister of the bride in the Kabul bombing being buried in her beautiful Hazara silk wedding costume, that were circulated by grieving Hazaras on Facebook. Only, instead of finding an outlet for his frustration and sad war memories in writing about Islamic realms as I did as an author, he found a salve for his grief in the rich texture of his people’s handwoven carpets.

Rezayee, Kabul/Boston. For me, as an immigrant to the remarkable panagah or sanctuary that is America from the Afghan capital Kabul, the Hazaras are not ‘Afghanis’ (the term for Afghanistan’s currency) or mere blurring abstracts from yet another mind-numbing story of death in a warzone that is so remote it might as well be on the moon; they are my friends, cousins, aunts, uncles, sisters, brothers, and most importantly, my wonderful, bright, precocious nieces—who are still there defying death at the hands of Taliban morality enforcers to get an education— and they are my qaum, my tribe. I had to force myself to breathe as I looked at the photos of the senseless wedding bloodshed on the internet from my safe home in Boston.

For me, the images of the devastated groom Mirwais and his inconsolable bride Raihana, who have said they would rather be dead and buried alongside the rest of their slain loved ones, are simply unbearable. The long history of massacre and mass murder of my people, displayed yet again, this time in the unprecedentedly demonic wedding bloodbath in western Kabul, has brought Hazaras in Afghanistan and abroad, where we have been scattered to the four winds, together like a family trapped in a basement from a tornado. It is a basement I have lived in since I was first arrested in a police sweep in Kabul and tortured via electrocution as a teenager. That dark memory is only one of many painful memories I have to live with day in and day out.

Rezayee in Kabul as a teenaged kite-flyer, a traditional Afghan hobby made famous in the West in Khaleed Hosseini’s bestseller The Kite Runner, with his kite tribute to American and Afghan friendship featuring both countries’ flags.

PTSD is a gloomy blanket that can enshroud one for life. An unexpected sound, smell, or scene, a random phone call, or especially a news report from faraway, like this recent story of families wailing for lost loved ones in a mass burial following the wedding massacre, can trigger it, sweeping me away 7,000 miles to the other side of the world to my birthplace. There are clinical ways to cope with PTSD, but I have chosen to deal with my pain by painting the red carpets of my people, like the very ones I and my refugee family wove to earn money to support ourselves in neighboring Pakistan after fleeing the war.

It is true that red is the color of the blood that was spilled in the August abomination that took place in what should have been a celebration of faith, family, hope, community, and the future, but it is also the color of my warmest memories from my watan, my childhood homeland. Red is the glorious color of gul-e-surkh, the wild lalah tulips that blanket the valleys of the Hazarajat, my people’s ancestral mountain homeland, in the spring during the Nowruz New Year celebration. But most importantly for me, red is the soothing pigment of the Hazara carpets whose deep, rich, red hue, known as royan, comes from the madder bush that is collected in mountain glades. It is the reddish choobi or vegetable dye made from walnuts, pomegranates, and the reseda plant that I used to prepare as young man to meticulously weave various shades of red into “Kazak” nomad-style carpets in the scorching heat of Pakistan among thousands of other Hazara refugees in the sprawling Haji Camp neighborhood of Peshawar.

Rezayee holding a “Kazak” carpet featuring ancient, nomadic anthropomorphic designs with his Boston ‘family’ including Williams to his right in Red Sox cap.

We Afghans have a saying, “You cannot wash away blood with blood.” But I paint life-size versions of my people’s red carpets to wash away the painful memories of bloodshed and to connect to my people’s craftwork. Our carpets are unmatched in their beauty and that has made Hazaras famous throughout Eurasia as weavers of anthropomorphic designs traceable to the primeval Hun, Mongol, and Kazak horsemen of the plains of Eurasia and the floral patterns of ancient Persia.

I often reflect on the journey to my new home Boston, a resilient, previously terrorist-targeted city filled with friends who I see as family, that is defined by its defiant, post-marathon bombing mantra that I admire so much, “Boston Strong.” As I look back on my flight from my former homeland to my new home Boston, I sometimes wrestle with the demons of survivor’s guilt. I am here, safe. They, the groom and bride, Mirwais and Raihana, my incredibly brave nieces, and so many of my people are still there, in that beautiful, but sad land I still love.

Even as I live here in a safe, vibrant city defined by its enlightened openness to outsiders like myself and enveloped in a blanket of safety that my embattled people in Afghanistan can only imagine, ISIS, the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and other demons of their ilk masquerading as men, are sharpening their knives in anticipation of the abandonment of our land that Trump has signaled with his recent troop drawdown announcement. My people live in dread of the post-American return of the Taliban tormentors to our rebuilt, bustling capital and to our Central Highlands of Hazarajat, and we believe one thing. The day the Americans leave, the Taliban will be back on our doorsteps to take their dark vengeance on us for our having sided with the Americans, just as the stalwart, pro-American Kurds of Syria were attacked by invading Turkish forces in October for daring to fight alongside the recently-withdrawn US troops against ISIS. This time when the dark enforcers come, we fear it will be worse than last time when the Taliban massacred thousands of our people in an attempted 1998 genocide in places known to us, like Dai Kundi and Mazar-i-Sharif, but known to few beyond the borders of our land.

Rezayee painting a “Kazak” nomadic carpet in his studio in Boston.

While most Americans are disconnected from the horrors in Afghanistan that have shattered the lives of so many young dreamers like Mirwais and Raihana, and many in America may even believe Trump’s hubristic brag that he “obliterated” or “wiped out” ISIS and that the remaining 13,000 US troops in Afghanistan can therefore come home, the burnt bodies of 80 Hazaras who were remorselessly killed by the far-from-beaten jihadist tormentors of my people are a silent testimonial to the terrorists’ enduring resilience. The dozens of coffins buried in a mass funeral by their grieving friends and family are also a mute rebuttal to the president’s false “Mission Accomplished”-style boast of victory over the fanatics that was made following the March 2019 Kurdish capture of ISIS’s last bastion in Syria.

I fear that the dark-hearted men of Afghanistan, who long to once again turn my land into a harsh, religious prison camp, and the increasing number of cold-hearted people here in America who do not feel that suffering people fleeing from lands plagued by horrors—like the one that took place in that wedding hall—are worthy of asylum, will prevail. Should my people, who have fought so bravely for freedom and democracy alongside US troops against the Al Qaeda 9/11 terrorists, their Taliban hosts, and ISIS beheaders of Americans, be soullessly abandoned the way Trump recently abandoned the anti-ISIS democratic Kurds of Syria, I know much blood will be spilled. When that blood is spilled and our villages are set aflame by the black-turbaned Taliban invaders, the red carpets I loved from my childhood will be but a memory. The magnificent handwoven carpets of my youth, whose weaving was forbidden when the cruel Taliban ruled our mountains, will be the fading echo of scream of torment from a once vibrant land; a distant, forgotten land that will be consumed by the raging fires of fanaticism that will surely send many more of my people fleeing abroad in my footsteps in search of panagah.

Should that dark day come, I pray that my American countrymen find it in their hearts to put aside blanket, broad-brushstroke bans on Muslim peoples like the pro-American Hazaras and equally pro-American Kurds, reject blind, xenophobic fear of others, and instead offer my people the same sanctuary I have found in this wonderful land I now proudly call my watan, my homeland.

Brian Glyn Williams is Professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth and author of Counter Jihad. The American Military Experience in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria and a book based upon his summers spent with the Uzbek Mongol anti-Taliban horsemen of northern Afghanistan The Last Warlord. The Life and Legend of Dostum, the Afghan Warrior who Led US Special Forces to Topple the Taliban Regime. He worked for the US Army’s Information Operations in Kabul and for the CIA’s Counter Terrorism Center in eastern Afghanistan. His website can be found at: brianglynwilliams.com

Javed Rezayee moved to the United States in 2006 after working with the United Nation’s DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration) program helping warlords and ex-combatants resume a civilian life in the war-torn Northeast. Rezayee earned his B.A. from Tufts University where he also taught storytelling. In New York, he worked for George Soros’s Open Society Foundation. In addition to eight years of working in the nonprofit and human rights fields, Rezayee has authored several short stories based on his childhood, including Black Kitty of Kabul. When not painting the beloved carpets of his youth, his preferred pastime is cooking his favorite Afghan dishes for friends and family and spending time with his baby niece.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved