J.M. Opal | –

In the face of mass protests against anti-Black policing and racism in the United States, President Donald Trump first dialed the country back to 1967 by tweeting an old quote from the surly police chief of Miami, who made it known to the activists of that era that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Now, Trump looks to a much older way to threaten the protesters — the Insurrection Act of 1807, which empowers the president to use U.S. military forces on U.S. soil.

Where did this law come from? What can America’s situation in 1807 tell us about its crisis today?

The mysterious Mr. Burr

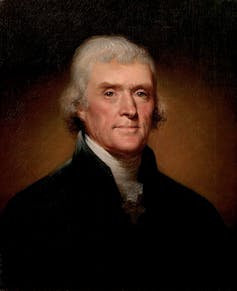

(Rembrandt Peale), CC BY

As he began his second term in office in 1805, President Thomas Jefferson had to cope with a secessionist plot led by his former vice-president, Aaron Burr. After killing Alexander Hamilton in an 1804 duel, Burr — now the amoral villain in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical — moved west down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, looking for recruits with whom he could take over New Orleans and become Emperor of Mexico.

Or something like that. Burr was never very forthcoming about his plans.

Jefferson got wind of the scheme in late 1806 and wondered how to shut it down. The Constitution gave the president clear permission to call up state militias in cases of imminent threat, but there was no reliable militia along the western frontiers.

So Jefferson’s majority party, the Democratic-Republicans or simply “Republicans,” passed the Insurrection Act in March 1807.

That’s the short story. To understand this law, however, we must look beyond Burr’s malfeasance and think about the extreme insecurity of the United States in 1807.

Uncertain Union

The early United States did not have effective control of anything west of the Appalachian Mountains, even though the Treaty of Paris of 1783 had given the new country paper title all the way to the Mississippi River. Jefferson’s purchase of Louisiana in 1803 made this insecurity worse.

In those vast western regions, Indigenous nations such as the Cherokees, Creeks and Sioux competed for power and resources, avoiding white Americans when possible and fighting them when necessary.

Those white settlers had little regard for the government in Washington; many of them preferred Spanish territory west of the Mississippi, where the laws were more forgiving of debtors. A good number were wanted for crimes back east, just like Burr.

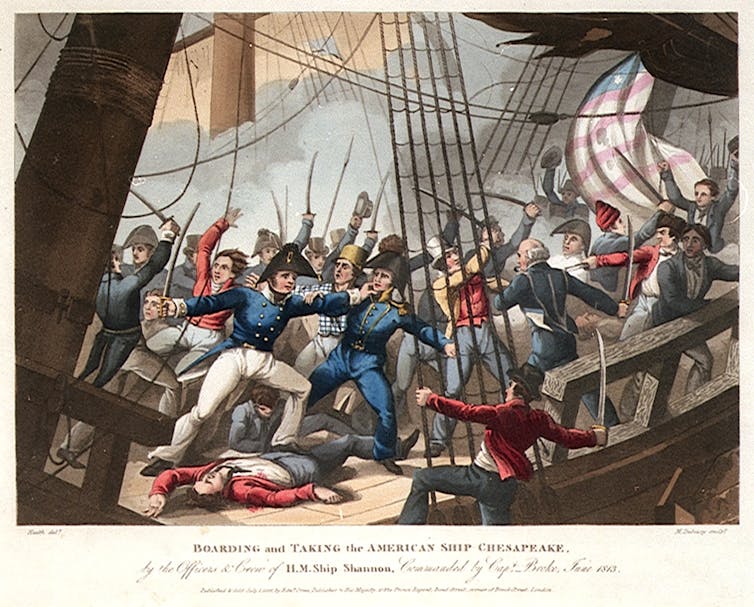

(William Dubourg Heath/National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London), CC BY-NC-SA

While dealing with the former vice-president’s scheming, Jefferson also had to worry about the mighty British. Fully expecting the United States to split up or collapse, the British government kept troops and ships along the Great Lakes to the north and the Gulf Coast to the south.

In 1805, the British also began to stop American ships along the East Coast and then, to “impress” any Irish-born sailors they found on board, compelling those sailors to serve in the Royal Navy for the great war with Napoleon. In the summer of 1807, a British warship even took sailors off a U.S. navy ship near the Virginia coast.

In short, Jefferson’s America was vulnerable to attack from all directions. Even worse were the enemies within.

The rival Federalists, once the party of Founding Fathers like Washington and Hamilton, were increasingly pro-British. Based in New England, they tried to block Jefferson and the Republicans at every turn, all but paralyzing the fragile Union.

In his first inaugural address in 1801, Jefferson had famously said, “we are all republicans: we are all federalists.” But 10 years later, as war with Britain approached, he could only conclude: “the republicans are the nation,” whereas the Federalists were something else — an alien group whose ideas of America threatened its survival.

From 1807 to 2020

Aside from their racism, Thomas Jefferson and Donald Trump have little in common. Jefferson’s “republicans” were the forerunners of today’s Democratic Party, not the GOP. For all his hypocrisy about slavery, Jefferson’s instincts were more democratic than authoritarian.

And he was a serious student of the Constitution and the wider world, whereas Trump couldn’t care less.

And yet, there is a troubling parallel between the state of the union in 1807 and 2020: due to the extreme partisanship of the past 50 years, America’s national concept is again fractured, its body politic broken and bleeding.

Once more, Americans feel dangerously insecure, besieged not by the hostile designs of other nations but rather by their incompatible views of each other.

This time, Americans are led not by a president who reluctantly faced the profound divisions of his day, but rather by one who relishes any chance to injure and insult the clear majority of people who don’t share his sense of greatness.

In Jefferson’s time, the crisis passed because the Federalists disappeared after the War of 1812. Having opposed America’s second war of independence, they quickly faded. Their ideas of the country were discredited and rejected. Today, we can only hope that a bigger, more generous view of American nationhood can emerge peacefully and decisively.

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved