Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Lebanon may have survived its bubbles and wars decades ago, but the combination of economic crisis and the coronavirus may have put it in a serious position once again. During the pandemic, Lebanon’s once-vibrant tourist industry is moribund (some two million visited the country of four million in 2019), and coronavirus lockdowns have devastates workers and local industries.

Embed from Getty Images

BEIRUT, LEBANON – JUNE 11: People gather to protest against dire economic conditions and depreciation in the value of the Lebanese pound against the dollar due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the Lebanese capital Beirut on June 11, 2020. (Photo by Houssam Shbaro/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Lebanon has all the hallmarks of a failed state. It has lost control over its monetary policy (the currency, pegged to the dollar specifically to prevent this from happening, has lost 70% of its value since October), and its attempts to exert control over its fiscal policy with absurd taxation measures have resulted in plummeting support. Its central and private banks are despised. Its educational institutions, once second to none in the region, are abysmally run and now sliding into irrelevance. Its infrastructure—including basic indicators of development like water, electricity, and sanitation networks— barely functions, being paralyzed by entrenched elites.

Even its famed hospitals are underfunded and have been approaching the coronavirus with a worryingly laissez-faire attitude, to the concern of the head of the Hariri University Hospital.

Embed from Getty Images

Protesters chant slogans as they gather for a demonstration against dire economic conditions in the Lebanese capital Beirut’s southern suburb late on June 11, 2020. – The Lebanese pound sank to a record low on the black market on June 11 despite the authorities’ attempts to halt the plunge of the crisis-hit country’s currency, money changers said. Lebanon is in the grips of its worst economic turmoil in decades, and holding talks with the International Monetary Fund towards securing billions in aid to help overcome it. (Photo by ANWAR AMRO/AFP via Getty Images)

Demonstrations, already common since late last year, have been growing rapidly since Lebanon defaulted on its international debts earlier this year.

The currency is in freefall. The once powerful Banque du Liban (BDL) is reviled; protesters in Tripoli burned its local offices last week. Riad Salameh, the longtime BDL governor, has dug in, igniting a feud with the premier and arguing that claims about the currency exchange rate are “untrue.” Banks keep closing and reopening.

During the period of French rule over the country a hundred years ago—legally supposed to be temporary, although the French had no intention of leaving—the nationalist politician Yusif al-Sawda pessimistically commented that “little Lebanon spells economic death; union with Syria, political death.”

It didn’t always look like he would be right, and he was hardly a prophet. For a few decades after Lebanese independence, Beirut — the glitzy financial capital of the eastern Mediterranean— seemed to demonstrate that “little Lebanon,” the geographically smallest country in mainland Asia, with sparse natural resources, a high rate of emigration going back decades before independence, a rugged topography, and constant conflicts with its neighbors to the south and east, was managing to pull itself into economic modernity. Despite constant political rumblings, it looked like little Lebanon was a success story.

When most people today think of Lebanon, they think of the fifteen-year-long civil war. Occasionally they think of the 2005 expulsion of Syrian troops from the country, or the 2006 war with Israel. Sometimes, real history nerds will think of 1958, when the US Marines and Lebanese right briefly fought with Arabists in the Lebanese government. It’s always seen as about the wars, though.

It is important to underline that Lebanon has seen economic troughs and banks collapsing before, and has somehow survived. Another Yusif, Yusif Baydas, opened Intra Bank in 1951. By 1966, due in part to Baydas’s politicking, the bank had problematic control over the Lebanese economy and the Lebanese currency market. Although his mother was from Beirut, he had been born in Palestine and had been granted Palestinian citizenship in 1925 by the British Mandate. During 1948 War, he and his pregnant wife fled to Beirut, his mother’s city. As we have seen, he prospered beyond imagining and by the mid-1960s, as much as 17% of bank deposits in Lebanon, and nearly 40% of deposits at Lebanese banks, were with Intra. Intra also made Beirut look like a safe investment destination for international investors, taking advantage of their jitteriness at the path Nasserist Egypt was taking. Air Liban, the Casino, and Beirut Port were under Intra’s control.

In 1966, Intra suddenly collapsed. The causes were external; the US was forcing international currency markets to raise interest rates on the dollar. Baydas, who had put his eggs in the US dollar basket, was taken by surprise and found his bank had limited liquid assets. When worried depositors retrieved their money, Intra was left with nothing. The new Banque du Liban (BDL) had the power to prevent Intra’s collapse. But Baydas had antagonized many in the government with his relatively stringent policies on personal loans, and his ancestry was of concern to the deeply anti-Palestinian political establishment. His rivals, the Eddé brothers, were aligned with the elite. In the two years between Intra’s collapse and Baydas’s death, Baydas was convinced that the government prevented the BDL from rescuing him.

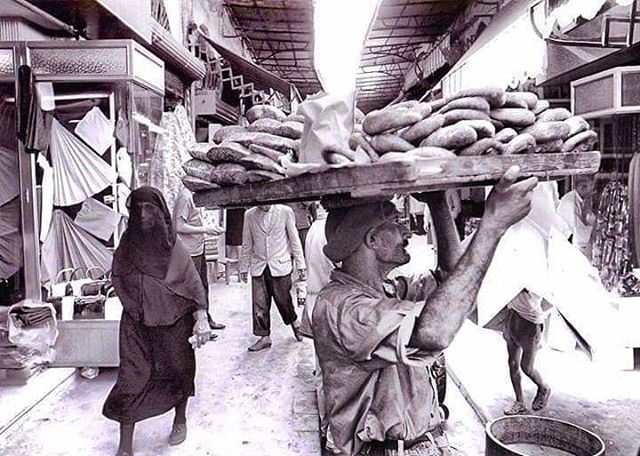

Photo of Souk Ayass, Beirut, in 1966 by Mounir Diab. H/t Wikimedia.

The damage was done, and investors had lost interest in Lebanon. The country’s economy, heavily dependent on finance, was left to stagnate after the shock caused by Intra’s collapse had dissipated.

Flash forward to June, 2020. Today, the Association of Lebanese Banks has joined alongside Banque du Liban head Riad Salameh in turning on the government. The BDL is trying to stabilize the exchange rate by throwing US dollars into the country. This time, though, the combination of the novel coronavirus and collapse means that little Lebanon may be facing a dire test. And without a strong public infrastructure, it certainly cannot handle a pandemic. The question is whether it can come back from catastrophe, as it did after 1966 and again after the Civil War in the 1990s. If so, recovery will depend heavily on the working class and the poor. Most Lebanese I know with means to leave the country have done so, moving to France, Armenia, Belgium, and the US.

——

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

Al Jazeera English: “Protests rock Lebanon as currency collapses”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved