Ann Arbor (Special to Informed Comment) –

Donald Trump initially threatened to deploy federal agents in the city to clamp down on protests, though later tried to switch reasons in the hope that we already forgot. This is not aimed at rural voters, though—it is aimed at suburbs. Trump has long realized that by raising the spectre of integration between the city and its suburbs, he can sway suburban voters to his cause while also demonstrating that he is able to “restore order” to a city that has an undeserved reputation for violence.

The Detroit mayor is having none of it—he issued a joint statement with the Chief of Police saying that Detroit has “no need” for federal intervention. Rashida Tlaib, true to fantastic form, said that federal agents had “messed with the wrong district.” But none of these people can speak for the suburbs.

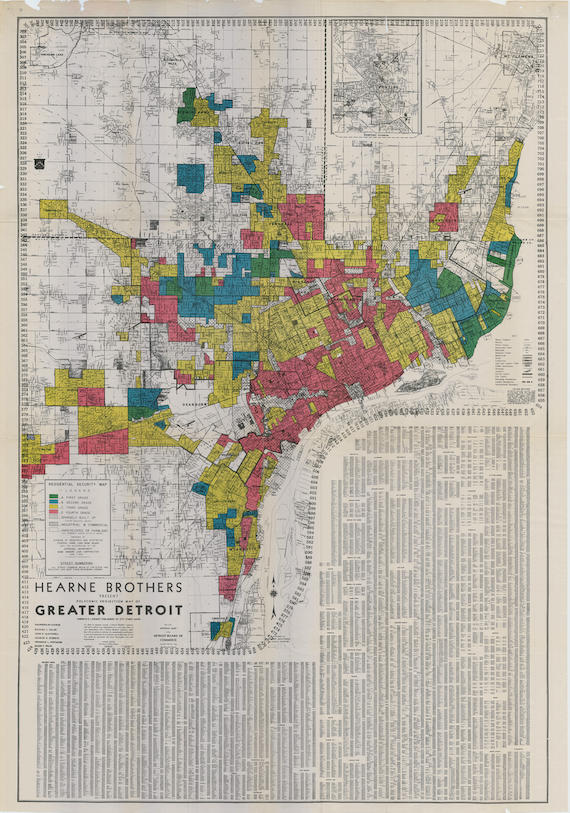

Courtesy of Detroitography.

The causes for the rise of suburbs in Detroit is charted in detail by historians such as Thomas Sugrue, Heather Ann Thompson, and Richard Rothstein, as well as innumerable urban and labor sociologists: the Great Migration, the return of Second World War veterans, Reuther’s “Treaty of Detroit,” cheap home construction, forced segregation of public housing, redlining, blockbusting (when realtors deliberately scared white city residents into selling their homes at a discount, then inflated prices for incoming Black residents), and more. Deindustrialization hit the city hard, and as layoffs roiled the region, unions began playing defensively, generating tension between conservative American and militant Canadian auto union locals. Meanwhile, since the 1967 riots and the subsequent unrest, as well as the 2013 bankruptcy, Detroit has become almost synonymous in the North American imagination with decline, decay, and mismanagement.

The trend is perhaps clearest when race is explicitly considered. Between 1910 and 2010, whites in the city of Detroit dropped from 98.7% of 466,000 people to around 10% of 750,000 people. Two-thirds of Black residents of Metro Detroit live within the city itself, kept there by the lingering aftereffects of real estate inequity. Metro Detroit remains one of the country’s most highly segregated zones. Eight Mile Road continues to serve as “the tracks”—beginning in the 1930s, a literal wall was built on a stretch of Eight Mile dividing Black neighborhoods from whites-only housing developments near Eight-Mile, with whites later fleeing north of it,* and even during the coronavirus pandemic, the street serves as a poignant and often deadly reminder of segregation.

Despite this, the population of Metro Detroit has always been mostly white, and surprisingly to many, the population of Metro Detroit has not declined too much—it has simply moved around and become ever more segregated. Educational and banking institutions, suburban municipalities, road networks, and blunter tools such as prisons continue to reinforce and deepen racial inequity throughout the metro region.

This story in general is well-known in Southeast Michigan, even if the statistics are not often given. It is a common story throughout the United States. I grew up mostly in Cleveland’s suburbs, which saw many of the same trends.

Courtesy Truman Library.

When Trump deploys federal agents to Detroit, he is not concerned with crime per se. He is concerned with Crime as a rhetorical tool. He knows where the population and power reside in Michigan’s densely populated southeast, and he believes that using law-and-order language will subconsciously rally the decisive bloc of suburban voters to his side. The feds do not need to do anything; in fact, as Portland showed, the less they do, the better. Their televised presence will calm the nerves of suburban Michiganders who have been trained for decades to view Detroit as a locus of crime and destitution in need of order.

We will soon see whether the strategy works or not. It is a clever trick, unoriginal yet time-tested. But there are a few solutions, both short- and long-term.

For starters, we must recognize that Detroit’s failings are primarily due to real estate, industrial, and banking interests hijacking a city’s municipal machinery to suit their own ends. (The same goes for many other cities across the region, including Flint and Cleveland.) When Americans vote in November, we can strike a blow against these interests, particularly in down-ballot races but also in the presidential vote, which will in turn affect bodies such as the National Labor Relations Board and the Department for Housing and Urban Development.

I recognize that voting is meaningless when not backed by community and workplace organized action. Strong unions are difficult but not impossible to organize in right-to-work states, and tenant rights groups have seen moderate success during the pandemic.

The long-term solution may be more difficult to swallow, but it is vital in the long term and has worked in the past: Detroit’s suburbs need to be integrated, certainly through pooling of resources and probably through eventual annexation. Currently, affluent suburban residents are taking advantage of their proximity to a major economic and border hub while funding segregated schools and utilities only for themselves—something that they were explicitly allowed to do by the Burger Supreme Court in Milliken v. Bradley. This privilege, hard-won by affluent suburbs, is also vociferously defended.

But there are success stories in amalgamation; Indianapolis, Indiana and Sudbury, Ontario both annexed surrounding suburbs and are in the process of deepening integration between the central and peripheral regions. It is not something that can be done haphazardly. But in the long term, I am not sure another choice exists.

~

* A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Eight-Mile Wall ran east-west, parallel to Eight-Mile Road, rather than north-south to segregate a whites-only housing development from Black neighborhoods. The author apologizes for the error and wishes to thank Jeremy Barth for the correction.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved