Eau Claire, WI (Special to Informed Comment) – On July 11, the New York Times reported on the Iran-China new economic and security partnership, detailed in an 18-page proposed agreement, that would clear the way for billions of dollars of Chinese investments in energy and other sectors. The proposed 25-year roadmap between Iran and China is titled “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the I.R. Iran and P.R. China” and in its opening statement says: “Two ancient Asian cultures, two partners in the sectors of trade, economy, politics, culture, and security with a similar outlook and many mutual bilateral and multilateral interests will consider one another strategic partners.”

The partnership would vastly expand Chinese presence in banking, telecommunications, ports, railways, and dozens of other projects. In exchange, China would receive a regular and discounted supply of Iranian oil over the next 25 years. The document also describes deepening military cooperation, potentially giving China a foothold in a region through joint training and exercises, joint research and weapons development, and intelligence sharing. All this would then undercut the Trump administration’s efforts to isolate the Iranian government because of its nuclear and military aspirations. It has been argued that “even the partial implementation of a Chinese-Iranian strategic partnership would signal a major escalation in the U.S. strategic competition with China and blow a hole in the administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran at the same time.”

The reaction to the deal from inside Iran and the outside have been varied, pending on the ideological and political foundations of such opposition. The Iranian groups and individuals opposing the Islamic Republic establishment have been swift to label the deal as one of the sell-outs to the Chinese at the expense of Iran’s national interest but to the benefit of the ruling regime. The U.S. State Department for its part referred to the planned agreement as a “second

The Iranian leadership is accused of being afraid to share the details of the pact because “no part of it is beneficial to the Iranian people.” Inside Iran, former President Mahmud Ahmadinejad warned in a speech in late June that a 25-year agreement with “a foreign country” was being discussed “away from the eyes of the Iranian nation,” and former conservative lawmaker Ali Motahari, suggested on Twitter that before signing the pact Iran should elevate the fate of Muslims who are reportedly being persecuted in China. There are also hundreds of touted commentaries and video-clips on social media platforms, harshly condemning Iran’s political leadership of treason for ‘leasing and surrendering its sovereignty’ over the Persian Gulf Kish Island.

The details of the deal are yet to be published and the Iranian Parliament must debate and vote on the matter. President Hassan Rouhani’s chief of staff, Mahmud Vaezi, has reiterated that the framework of the agreement has been defined, adding that the negotiations are likely to be finalized by March 2021. Vaezi has also said the agreement does not include foreign control over any Iranian islands or the deployment of Chinese military forces in the country.

The debate inside Iran over the effect of US sanctions only exposes the divergent interests of the ‘pro-west’ and the ‘pro-east’ camps. The structure, organization and the future direction of Iran’s economy have been vehemently debated since the advent of the revolution. The debate is largely between ‘the private-marketeers’ and those favoring a more ‘state-dominated’ economy. Successive Iranian governments have followed domestic and foreign policies, always coming under attack as being either ‘pro-market’ and ‘pro-west,’ e.g., President Rafsanjani’s tenure, or as dominated by populist ideas and policies conceived as detrimental to sound political economy, e.g., President Ahmadinejad’s tenure. These camps regard themselves as either ‘conservative’ or ‘reformist’ but without clear delineations over policy choices and recommendations in tackling development challenges and social ills.

Embed from Getty Images

BEIJING, CHINA – DECEMBER 31: China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi shakes hands with Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during a meeting at the Diaoyutai state guest house on December 31, 2019 in Beijing, China. (Photo by Noel Celis – Pool/Getty Images).

In recent years, this polarization surrounds the debate over whether Iran should, after years of internal debate, sign into the

The absence of political parties in Iranian political scene has been a major contributor to the confusion over policy debates and options. The presence of powerful individuals, factions, and power elites have led to political squabbling and finger-pointing and unaccountability in a system that permits genuine political debate over policy options to degenerate into personal attacks and name-calling for policy failures. The failure to systematically implement economic privatization, that is protected in the constitution and supported by the top political leadership, or personal attacks on foreign minister Javad Zarif and his cohorts who negotiated the JCPOA for three years on behalf of the country, are two recent examples of political and ideological pandemonium due to the absence of delineated and structured political parties and platforms. Such political wrangling and uncertainties only diminish the significance and the potential benefits that the new Strategic Partnership with China can create. The new deal is an opportunity for Iran to break through its isolation but it should not mean the end of Iran’s ties with Europe and even the United States, as Iran’s geostrategic location has been and will continue as a bridge between the East and the West.

Iran’s Political Economy of Sanctions

Iran has since the revolution in 1979 experienced widespread economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure and has been portrayed as a pariah state in search of a nuclear bomb, part of an ‘axis of evil,’ a state sponsoring terrorism, and responsible for ‘proxy wars’ in the region and all that ills the region, including disarray in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, and perpetuation of war in Yemen! Iran in 2020 is the most severely sanctioned country in the world. As any keen observer would note, the United States’ primary difficulties are with Iran’s foreign policy doctrine and practice, and not so much its nuclear program. For Iran, the China deal is the result of more than forty years of the implacable US and its allies’ hostility toward the Islamic Republic.

Sanctions are injurious and hinder good governance. Sanctions affect the supply and demand and prices in an economy, causing inflationary pressure, particularly a rentier economy with heavy reliance on imports of manufactured products and the technology associated with it. Sanctions also contribute to misappropriation of resources and increased corruption, rentierism (rant khary), inflation, income and wealth gap, popular discontent, and even social unrest.

Sanctions have disadvantaged American and Western companies of a lucrative market in Iran. Western companies like Peugeot, Renault, Volkswagen, Total, ENI, Samsung, among many others, have, fearing US legal and financial reprisal, abandoned Iran’s mark. The auto industry is a key driver of Iran’s economy, the operation, and prosperity of which keeps more than 60 other industries moving. The industry “is only second to its energy sector, accounting for some 10 percent of the gross domestic product and 4 percent of employment.” Foreign companies that made cars in Iran decided to leave after US President Donald Trump revealed new sanctions on the Islamic Republic. Renewed sanctions led to delays in car deliveries and a shortage of parts and by June 2018, a month after sanctions were renewed, “car production dropped by 29 percent contrasted with the same month a year earlier.”

The dollar has progressively been weaponized to undermine governments opposing US views on global relations, as in Iran, Venezuela, Cuba, Russia, and a host of other countries. Without access to the SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications system), Iran is practically robbed of almost all international transactions, including receiving money for its oil exports. The US Institute of Peace reported in 2012 that Iran was using more than 60 tankers—roughly two-thirds of its tanker fleet–to store up to 40 million barrels of crude oil at sea while it located buyers.

AsBloomberg reported on April 26, 2020, “Denied services by the solitary bank that had been used by Chinese authorities to defy U.S. secondary sanctions for over a decade, Iranian executives have been forced to turn to what they call chamedooni (suitcase) trade, referring to payments made in cash and transported across borders in hand luggage…by using front companies and payments routed through third countries or paid in cash, Iranian firms and their most loyal Chinese partners should be able to ensure that bilateral trade doesn’t hit zero. But the inefficient and opaque methods now required to facilitate payments will put an inherent limit on how much trade can take place.” The International Monetary Fund for its part has given lip service to Iran’s legitimate request for assistance to stave off the coronavirus in defiance of their proclaimed ‘neutral stand’ in the management of international monetary exchanges and development assistance and guidance!

The oil sector exports fell from around 70% of the total export ($68.5 billion) in 2017 to nearly 50% in 2019 ($59.3 billion). By July 2019, Iran’s total oil exports fell to as low as 100,000 bpd, down from around 400,000 bpd in June. Even China changed its buying patterns. It doubled its oil imports from Saudi Arabia from the previous year. Beijing imported 1.8 million bpd from the kingdom in July, up from 921,811 bpd in August 2018.

Iran “was exporting 2.7 million barrels per day—775,000 bpd to China or 29 percent of total sales. By September 2018, the Islamic Republic’s total exports plummeted to 1.3 million bpd.” Eventually, Iran resorted in January 2019, to offer discounts to Asian buyers. It “cut the price of Iranian light crude by $1 per barrel, approximately 30 cents a barrel lower than Saudi Arabia’s light crude. It was the largest discount Iran had offered against Saudi prices in more than a decade.”

The Central Bank of Iran (CBI) monetary policy is also considerably challenged and swayed by the US sanctions. For example, the ongoing volatile currency market in summer 2020 that has seen the further depreciation in Iran’s rial is, separate from domestic wild speculation in the currency and gold markets, partly a result of increased liquidity in the market, itself due to vast government borrowing to finance social welfare and economic policies in the age of COVID-19 pandemic.

President Rouhani’s government has borrowed a vast amount of rial through issuing bonds against the hard-earned foreign currencies in the possession of Central bank for national development projects. Indicating budgetary pressure on the government to fulfill all its obligation, CBI announced on August 5 that domestic bonds issuance that began in early June had earned the government more than $2.1 billion in new resources. These bonds were offered in maturities of one to four years with yields between 16.7 to 19 percent. Given Iran’s complex and polarizing politics and sanctions pressure, the CBI remains helpless in its command over foreign currency holdings and independent monetary policy and thus a supervisory and controlling role over the value of the rial.

The overall damaging impact of sanctions cannot be overlooked, notwithstanding some may argue that sanctions are a blessing as it has compelled the country to become self-reliant in certain sectors of the economy as in the defense and nuclear programs. To Iran’s credit, the country has slowly moved away from a rentier economy over the past forty years toward a ‘welfare state’ with increased reliance on food production, non-crude, petrochemical commodity export, and tax collection revenues.

The Iranian economy has reduced its dependence on the export of crude oil, although the oil sector remains central in the country’s earned foreign currency. The Rouhani government’s proposed 1399 (2020-21) annual budget (570, 000 Billion Tomans) projected an unparalleled 30.7% collection from taxes (175,000 Billion Tomas) and only about 8.4% (48,000 Billion Tomans) from the oil sector while the share of government cash handouts and subsidies set is 23.5% (134,000 Billion Tomans). (These numbers are calculated by this author based on a reported recent interview with Mr. Muhammad B. Nobakht, Head of Iran’s Budget Organization.)

A Deal or A Partnership?

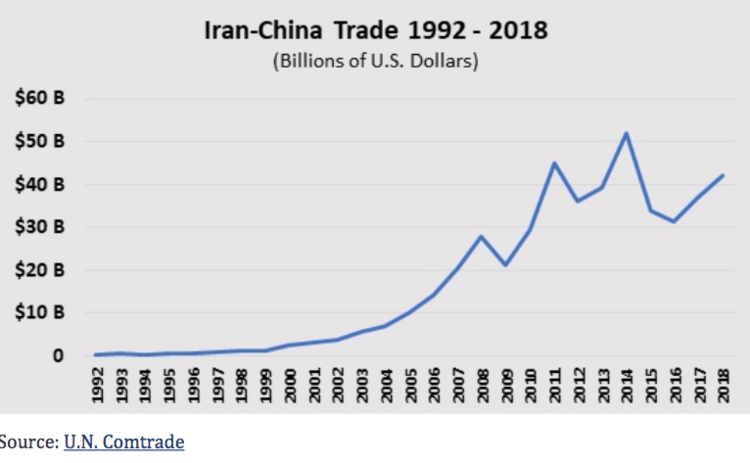

Iran is the most populous, geopolitically positioned, and developed country in West Asia, and it is only natural to seek a long-term trading partnership with the second (and soon to be the first) economy in the world. Iran also is in dire need of foreign investment in its energy and infrastructure projects, estimated at $250 and $150 billion in the coming years. Such projects necessitate long-term foreign direct investment (FDI) and commitment. China today is Iran’s biggest trading partner. Bilateral trade between the two countries rose from almost nothing in the early 1990s to more than $50 billion in 2014; it considerably increased from $400 million in 1990 to $1 billion in 1997, largely due to expanded energy trade. Between 2000 and 2012, China hovered between 9 percent and 14 percent of its oil imports from Iran.

Source: U.N. Comtrade

The discussions over the current strategic partnership proposal go back to President Xi Jinping’s visit to Tehran in 2016. According to Iranian officials, the deal would vastly expand Chinese investments in banking, telecommunications, ports, railways, and dozens of other projects in exchange for Tehran supplying Beijing with discounted oil for the next 25 years. The deal would also possibly include joint military training, exercises, counter-terrorism cooperation, intelligence sharing, and arms transfers to Iran. Iran-China relations is geared to set a roadmap for a multi-faceted strategic partnership.

China and Iran have suffered occupation and humiliation in the hands of the West, are believers in national self-reliance, and hold a ‘non-interference’ view in other countries’ national sovereignty issues. Both countries are chastised for their pursuit of national integrity and sovereignty and fending off Western interference, the roots of which date back to the cold war years, e.g., Taiwan, Tibet, and the Sino-India relations, the 1953 coup d’état and the support of the authoritarian rule in Iran, and sanctions and the overall animosity directed at the Islamic Revolution. Both countries are geostrategically located and can benefit from complementarity in resource possession, potential production capacities, and trade and security.

Iran’s geopolitical realities necessitate playing its role as a vital economic crossroad between the East and the West. The meaning of the deal remains: Persian Gulf can become the next borderline dividing the security and strategic interests of a rising China within an emerging ‘new cold war’ from the historical US interest in support of the conservative Arab States, Israel, and access to energy resources. Iran’s ‘bridging role’ success depends a great deal on the post-Trumpian American foreign policy position towards China in whole and US interest in the Persian Gulf and the greater Middle East in specific. At this juncture, a US return to the Iran nuclear deal agreement, JCPOA, is a must, and so is the acknowledgment that Iran is a pivotal state in the Persian Gulf, suggesting its participation in the regional peace and stability is essential. Otherwise, the option for a US political and diplomatic rapprochement with Iran is precipitously vanishing, to the likely detriment of Persian Gulf socio-economic development and security. As New Times reported on July 11, Iran and China were closing on a partnership deal in defiance of the US and that the investment and security pact would greatly extend China’s influence in the Middle East, throwing Iran an economic lifeline and creating new crossroads with the United States.

In security and military matters, “because Iran, like China, seeks to avoid import dependence, Beijing is a desired partner—willing to transfer knowledge and expertise as well as critical subsystems.” This has enabled Iran to produce its modifications of Chinese cruise and ballistic missile systems. Iran has also over the years “purchased advanced submarines, fighter aircraft, tanks, and surface-to-air missiles from Russia, but after 1995, when Russia pledged that it would not make further arms contracts with Iran, Iran resume looking to China for conventional arms.” Beijing also “recognizes that preventing Iran from improving its military is a U.S. priority, and it may exploit U.S. sensitivity on this issue to attempt to influence U.S. policies in other areas.

For example, after the United States announced it was selling F-16s to Taiwan, China revived a proposed transfer of M-11 missiles to Iran, which had earlier been canceled because of U.S. pressure. Ties to Iran thus provide Beijing with additional leverage in negotiations with the United States.” Similarly, Beijing has played a major role in Pakistan’s nuclear program to counter India and US pressure. In the 1980s, China apparently provided Pakistan with proven nuclear weapon design and enough highly enriched uranium for two weapons…China has also played an active role in Pakistan’s missile program. Furthermore, China, “with its UN seat and desire to reduce U.S. hegemony, was one of the few major powers willing to maintain strong and cordial relations with Tehran during the more radical days of the revolutionary regime.”

The Iranian-Sino partnership entails both a pull and push factor. Iran badly needs foreign investments and China can extend its reach into the Middle East via Iran while achieving its share of the one-road-one-built (BRI) initiative. The BRI that would connect China via land and sea with the rest of the world may be construed as China’s ambition at becoming a global player, but would this be to the disadvantage of countries involved in the project? The answer is a resounding no, given the historical Western colonialism of much of Asia, Africa, and South America that also included victimization of China (recall, a Western colonial expansion that began in the late 1400s, lasted until the end of World War I, resurrected through imperial ambitions, left a trail of plundering of resources, manipulation, slavery, genocide, racism, and even eugenics! The Western colonial and imperial involvement in China itself translated into more than 100 years (1800-1949) of foreign occupation, humiliation, territorial losses, mass starvations, and civil wars.

This is not to argue that China does not have ambitions to project power and influence beyond its region. China’s model of investment in the BRI project shows its investment in accessing minerals, raw materials, and infrastructural projects through leasing and control of resources. China’s investments involve mostly on resource extraction and infrastructural projects and less on the development of human capital in the targeted countries. Still, China is doing what no other private financial sector is willing to do: to invest hundreds of billions of dollars on projects that others dare not to invest, e.g., the Karakoram Highway project in Pakistan, with only the pledge of a return in the future through operational leases and control of ports and facilities for a defined-time-period, e.g., Vietnam, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Pakistan.

The Karakoram Highway project will cut China’s import of oil from the Middle East by two-third from 9000km via sea to 3000km. This will seriously augment China’s access to the oil-rich Middle East but will potentially improve Pakistan’s long-term national development that for decades has experienced poverty and significant income gap, political instability, terrorism, and military rule, factors easily dispiriting to any investors. Pakistan-China trade stood at only $6.2 billion in 2016 but is expected to grow exponentially. The Kashgar to Gwadar Port is part of the BRI project and involves projects in rail, port, energy, and construction development. It is projected to improve Pakistan’s GDP by 2-3% point in the next 15 years. The project is further creating an estimated 500-700 thousand jobs with a projected $3 trillion turnaround in trade and commerce. China in return has a 40-year lease of the Gwadar port.

China is doing what the World Bank has failed to do since the 1950s: to provide a sizable amount of state capital at a lower interest rate for development projects in the developing ‘third world.’ The IBRD has only delivered about $500 billion in loans to alleviate poverty around the world since 1946, with most of its funds collected in the world’s financial private markets with its shareholder governments paying merely about $14 billion in capital. China, on the other hand, relies on its own earned dollars and other hard currencies to finance the BRI projects with an estimated 1-2 trillion dollars over the years to come. This will extend China’s sway beyond Asia and into Africa, Europe, and South America. China is the first non-Western country in modern times challenging the Western path to development and hegemony, and that is an disconcerting proposition to many.

China is a regional power and its power will only grow in the coming years. The repercussions for US-Sino relations and global power politics of a rising China are paramount. China has greatly gained from the liberal international political economy since the 1980s, but it has always been hasty to presume that China will ultimately embrace the Western democratic political system, propagated by neoliberals in the United States and Europe. China may in the future accept a more competitive political system but recall that the path to (liberal) political democracy is grueling and takes decades, indeed centuries before it develops and matures. One only needs to study the experience with democracy and its development in the West. Yet, China is rising.

Conclusion

The signing of the Iran-China Strategic Partnership is only the natural outcome of a rational, calculated approach to foreign policy in the promotion of two country’s respective national interests. Indeed, there are always ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in any such agreement—and any human interactions–as different players within each country may wish to boost their own professed individual, group, elite, political class, and/or national interest. This produces confusion and disputes over what constitutes the national interest of a country in any matter! The state in China and Iran remain the central player in the economy, the polity, and society and the triangular State-business-labor relations.

Ultimately, the responsibility for the long-term national development of any national project lies with the host country. As stated above, there are always winners and losers in any human ventures, notwithstanding the wins and losses are, like anything else in life, relative. As such, major winners in the Iran-China Partnership are the national organizations and businesses associated with the state like the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and its affiliated companies and entities and various state-affiliated foundations. Iran is endowed with vast natural resources but, more importantly, it has an impressive human capital. Should the deal decisively end Iran’s Western-imposed isolation, the country can, if ensued with a sound approach to matters of governance, rapidly become a major economic, trade, and commerce powerhouse in West Asia. (It is noteworthy to mention discrepancies in views of government foundations and their role in the Iranian economy, like Bonyade Mostazafan, the Astane Qodse Razavi, or Setade Ejraye Farmane Imam: while the US Treasury claims foundations under the Iranian leadership has tens of billions of dollars in the country’s budget scheme, Iran authorities have always repudiated this. In a recent interview, an Iranian economist claims the foundations’ share of the national (not government’s) budget is 5.4% or under 3% of the country’s economy. This is in sharp contrast with Mostafa Kavakebian, a former parliamentarian and the head of Hizbe Mardomsalari or peoples’ party’s claim that foundations’ budgets are several times larger than that of the government!)

The Iran-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership deal is not one of a choice between the East or the West. Iran’s ‘pivot to Asia’ is not necessarily a pivot away from the West as much as it is a push away by the West. As Majid Reza Hariri, Chairman of Iran-China Chamber of Commerce has asserted, “it is others who refuse to cooperate with us. If we have no economic ties with the US following the 1979 embassy hostage-taking, it was the Americans who cut ties with us. Those who claim that Iran is being colonized by China can come and we will offer to sign similar agreements with them.” As for Europe, Paolo Magri, in Annalisa Perteghella, ed. Iran Looking East: An Alternative to the EU? comments: “the Iranian case powerfully demonstrates; it is the weakening of the transatlantic bond and the EU’s inability to play a leading role in safeguarding engagement with Tehran that ultimately made Tehran look east for alternatives.”

It is only through dialogue that the US and Europe can reach a compromise in their corresponding geostrategic and military/security calculations and priorities. For now, the view from Tehran is that no matter what Iran does, the United States will not stop its antagonism and pressure for regime change. The United States can and must recognize the legitimate role of Iran as a regional power with regional interest. This demands the acknowledgment that along with the rise of China the geostrategic realities in the Persian Gulf, and the wider Middle East, is changing.

—–

Bonus video added by Informed Comment:

Caspian Report: “China and Iran draft a $400 billion pact”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved