By Pooyan Tamimi Arab and Ammar Maleki | –

Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution was a defining event that changed how we think about the relationship between religion and modernity. Ayatollah Khomeini’s mass mobilisation of Islam showed that modernisation by no means implies a linear process of religious decline.

Reliable large-scale data on Iranians’ post-revolutionary religious beliefs, however, has always been lacking. Over the years, research and waves of protests and crackdowns indicated massive disappointment among Iranians with their political system. This steadily turned into a deeply felt disillusionment with institutional religion.

In June 2020, our research institute, the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in IRAN (GAMAAN), conducted an online survey with the collaboration of Ladan Boroumand, co-founder of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran.

The results verify Iranian society’s unprecedented secularisation.

Reaching Iranians online

Iran’s census claims that 99.5% of the population are Muslim, a figure that hides the state’s active hostility toward irreligiosity, conversion and unrecognised religious minorities.

Iranians live with an ever-present fear of retribution for speaking against the state. In Iran, one cannot simply call people or knock on doors seeking answers to politically sensitive questions. That’s why the anonymity of digital surveys offers an opportunity to capture what Iranians really think about religion.

Since the revolution, literacy rates have risen sharply and the urban population has grown substantially. Levels of internet penetration in Iran are comparable to those in Italy, with around 60 million users and the number grows relentlessly: 70% of adults are members of at least one social media platform.

For our survey on religious belief in Iran, we targeted diverse digital channels after analysing which groups showed lower participation rates in our previous large-scale surveys. The link to the survey was shared by Kurdish, Arab, Sufi and other networks. And our research assistant successfully convinced Shia pro-regime channels to spread it among their followers, too. We reached mass audiences by sharing the survey on Instagram pages and Telegram channels, some of which had a few million followers.

After cleaning our data, we were left with a sample of almost 40,000 Iranians living in Iran. The sample was weighted and balanced to the target population of literate Iranians aged above 19, using five demographic variables and voting behaviour in the 2017 presidential elections.

A secular and diverse Iran

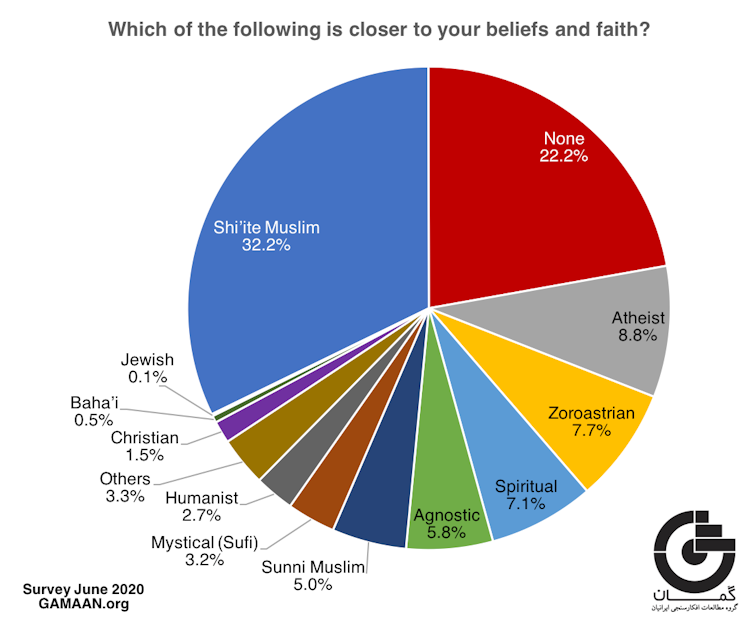

Our results reveal dramatic changes in Iranian religiosity, with an increase in secularisation and a diversity of faiths and beliefs. Compared with Iran’s 99.5% census figure, we found that only 40% identified as Muslim.

In contrast with state propaganda that portrays Iran as a Shia nation, only 32% explicitly identified as such, while 5% said they were Sunni Muslim and 3% Sufi Muslim. Another 9% said they were atheists, along with 7% who prefer the label of spirituality. Among the other selected religions, 8% said they were Zoroastrians – which we interpret as a reflection of Persian nationalism and a desire for an alternative to Islam, rather than strict adherence to the Zoroastrian faith – while 1.5% said they were Christian.

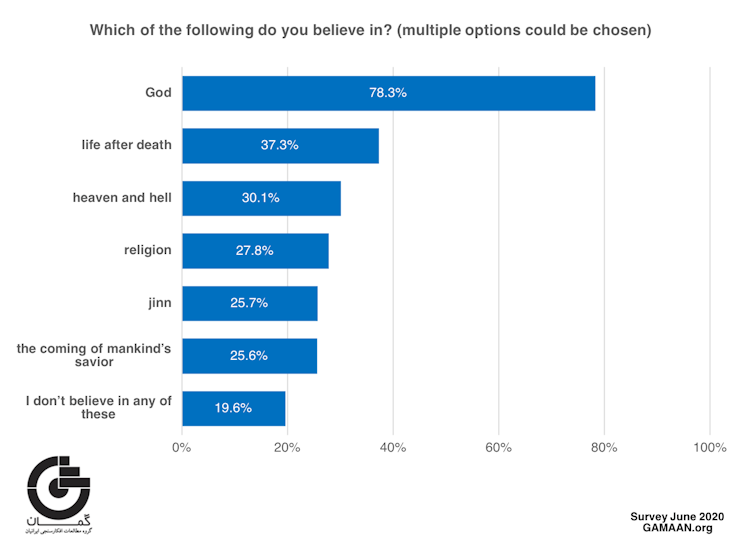

Most Iranians, 78%, believe in God, but only 37% believe in life after death and only 30% believe in heaven and hell. In line with other anthropological research, a quarter of our respondents said they believed in jinns or genies. Around 20% said they did not believe in any of the options, including God.

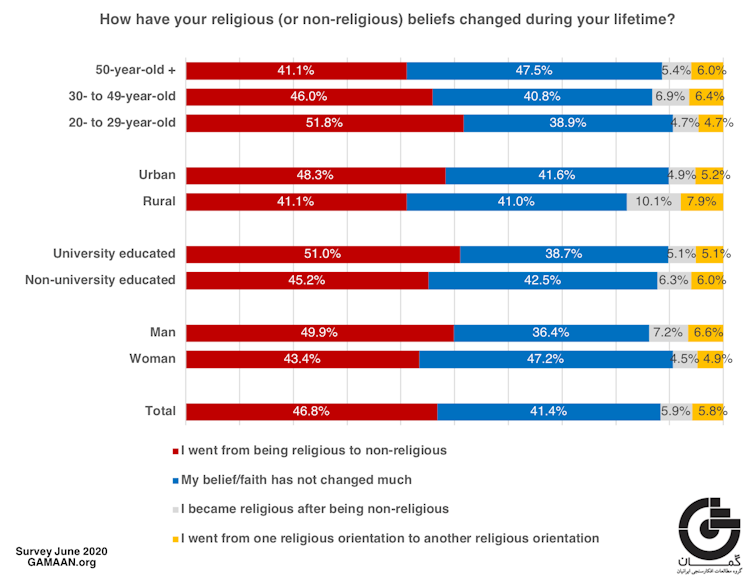

These numbers demonstrate that a general process of secularisation, known to encourage religious diversity, is taking place in Iran. An overwhelming majority, 90%, described themselves as hailing from believing or practising religious families. Yet 47% reported losing their religion in their lifetime, and 6% said they changed from one religious orientation to another. Younger people reported higher levels of irreligiosity and conversion to Christianity than older respondents.

A third said they occasionally drank alcohol in a country that legally enforces temperance. Over 60% said they did not perform the obligatory Muslim daily prayers, synchronous with a 2020 state-backed poll in which 60% reported not observing the fast during Ramadan (the majority due to being “sick”). In comparison, in a comprehensive survey conducted in 1975 before the Islamic Revolution, over 80% said they always prayed and observed the fast.

Religion and legislation

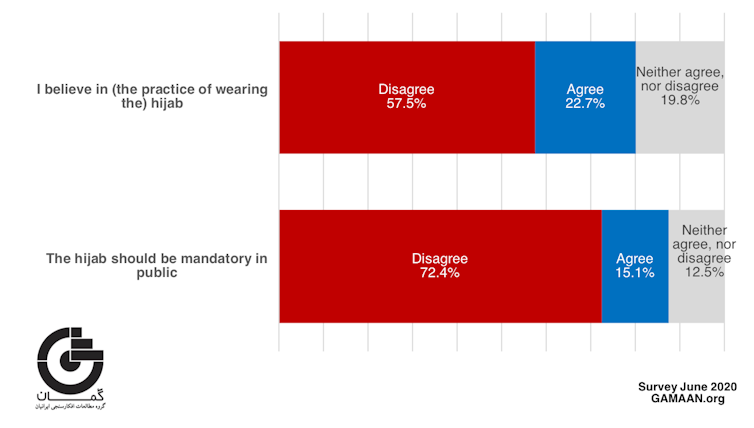

We found that societal secularisation was also linked to a critical view of the religious governance system: 68% agreed that religious prescriptions should be excluded from legislation, even if believers hold a parliamentary majority, and 72% opposed the law mandating all women wear the hijab, the Islamic veil.

Iranians also harbour illiberal secularist opinions regarding religious diversity: 43% said that no religions should have the right to proselytise in public. However, 41% believed that every religion should be able to manifest in public.

Four decades ago, the Islamic Revolution taught sociologists that European-style secularisation is not followed universally around the world. The subsequent secularisation of Iran confirmed by our survey demonstrates that Europe is not exceptional either, but rather part of complex, global interactions between religious and secular forces.

Other research on population growth, whose decline has been linked to higher levels of secularisation, also suggests a decline in religiosity in Iran. In 2020, Iran recorded its lowest population growth, below 1%.

Greater access to the world via the internet, but also through interactions with the global Iranian diaspora in the past 50 years, has generated new communities and forms of religious experience inside the country. A future disentangling of state power and religious authority would likely exacerbate these societal transformations. Iran as we think we know it is changing, in fundamental ways.

Pooyan Tamimi Arab, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Utrecht University and Ammar Maleki, Assistant Professor, Public Law and Governance, Tilburg University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured Photo: h/t Wikimedia Commons.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved