By Chris Myant

The targeting of Muslim food as a danger to public order was actually the first of the measures outlined in the president’s speech on 2 October.

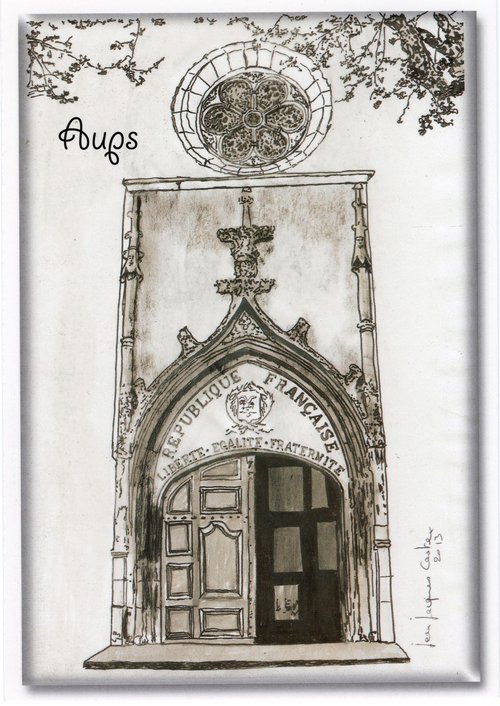

( OpenDemocracy.net) – In the small Provençal town of Aups, where the local Catholic church declares République française: Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité [The French Republic: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity], above its main entrance, there is a plain and nondescript monument put up in 1881. Its plaque announces that it is there: A la memoire des citoyens morts en 1851 pour la défense des loi et de la République – In memory of those citizens who died in the 1851 defence of law and the Republic.

Why think of that when watching Emmanuel Macron nail his colours to the mast of Islamophobia and announce that, if he gets his way, Muslim pupils in French schools will have days when they will eat the pork served up on their lunch plates or go hungry?

Aups was the scene of the final battle between a ragged force of locals who had taken up arms to oppose the coup d’état of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte and the troops of the local Prefect. The latter were party to Napoleon’s plot to remove the democracy installed after the 1848 Revolution toppled the monarchy established on the back of his uncle’s final defeat at Waterloo.

Louis-Napoleon’s supporters struck quickly at this one real attempt to block his coup of 2 December 1851. After their defeat at Aups on 10 December, a number of those thought to be the ringleaders were disposed of by firing squad. Many of the rest were sent off to forced labour in the new French colony of Algeria.

The Catholic church at Aups in the Var. | Some rights reserved.

There is just one mistake in the explanatory panel that the local council added a few years back to the monument. It talks of how “men from all over the Haut Var” converged on Aups. In fact, there were many women among the insurgents. Their names are there listed on the rolls of those hustled off to Toulon before the ships took them to Algeria. They are there in the columns of the regional press. The Toulonnais on 15 December reported that, two days after the battle, “Two women, armed with pistols and dressed in red, acting as cooks for the insurgents, have been arrested.” If you intend only to cook, you do not carry pistols.

These women were not just “seditious” and red, they were the purveyors of “the most odious passions” according to Hippolyte Maquan, a local royalist lawyer, who was the editor of a newspaper that effectively became the official journal for the Prefect during the weeks of resistance to the coup.

“One thought one was in the Kabyle (a region of Algeria, CM),” he wrote in a memoire a year later. “It was the smala of some Abd-el-Kader of the peasants’ cottages (the smala was the retinue of an Algerian leader, one of the last of whom to surrender to the French had been Abd-el-Kader, CM) . . . Why doubt that the Chapel of Mary, the Tower of David, the Boulevard of Christianity in the Middle Ages, dominating this countryside and delivered in the past from savage Saracen incursions, are today appealing to be purged, consoled and saved from the socialist invasion, this heresy with a bloody sensuality that would take us back to Muslim barbarity?”

The Haussmanian revolution

Oof! The author of these words did not hang about long in the area. The provincial lawyer and editor got promotion to Paris along with a Prefect he had been helping turn an elected President into an authoritarian Emperor. And who was this Prefect he had been assisting, this representative of the central government power, executing the orders decided on in Paris? None other than Le Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the Haussmann credited with creating the centre of Paris as we know it today.

One of the latest histories of those two hectic decades in which much of old Paris was knocked down and replaced with grand “Haussmannian” blocks of flats along spacious boulevards explains that the purpose was “the reconquest of the city centre by the well-off . . . the Haussmannian renovation undoubtedly significantly reinforced segregation” across the city.

The Prefect himself said he wanted to “open great strategic arteries going from the centre of Paris to the circumference, which will bit by bit drive the workers out to the exterior where they can be distributed and which will also help to keep an eye on them and contain them there as required.” He wrote that just after a visit to Paris by the Prussian general von Moltke who himself said of all this: “The workers are seeing themselves pushed out to the suburbs. But one can easily see why. This has a positive influence on the maintenance of order and public security.”

This is the way that Paris still is. Only what Haussman, Maquan and von Moltke would find different is that the workers pushed to the exterior are Black and Muslim as much as they are white. They inhabit the dense housing of departments like Seine-Saint-Denis to the north of the capital. Those who live in the Haussmannian centre of the city cross their tracks when they take certain Métro lines running north, pass the checkout in their supermarket, dodge the guys steering the giant rubbish bins to the dustcarts, tut-tut over the noise of the pneumatic drills recasting the pavement or slum it by taking a cheap Uber taxi to the Opèra.

Seine-Saint-Denis

Seine-Saint-Denis was a department that got an early mention in Macron’s speech.

There would be a “Republican awakening”, he explained, with a new law to be tabled in December. “The first axis of this awakening, of this republican patriotism, is a group of measures on public order and the neutrality of public services which form an immediate, firm response to circumstances reported and known, that are contrary to our principles. Local councillors, sometimes under pressure from groups or communities, have considered and can consider today imposing religious menus (the term he used in French was menus confessionnels) in the canteen. We have cases of this in Departments such as Seine-Saint-Denis but also in Normandy.”

This would be banned in future by law in the interest of “protecting the neutrality of public services and also the maintenance of public order. And this will in certain situations protect our local representatives in the face of such pressure.” If councillors did go so far as to vote in such menus, the Prefect would step in and reverse the decision.

All this is very slippery language. Notice that he did not say such menus had been introduced, only that they had been considered. And a menu confessionnel: is it the same thing as a menu de substitution, making available an alternative when pork is on the school meal menu, for instance?

So it is a complete non-question, a problem that does not exist? To think that would be a great mistake. Like so much else in Macron’s oratory, do not look at the immediate meaning of the words but at the public sentiments he is trying to play upon. The exercise is one of astonishing cynicism.

Like so much else in Macron’s oratory, do not look at the immediate meaning of the words but at the public sentiments he is trying to play upon.

In what possible way is it a danger for the stability of the world’s fourth nuclear power to let a child of nine ask the staff in their school canteen: “Could I have an omelette? I don’t eat pork.”

And why the child? When an Emir or a Sheikh from an oil-rich Middle Eastern state, let alone a Saudi prince, comes visiting the Elysée, does Macron command that the welcoming feast be based entirely on food a Muslim is expected not to eat? Of course we know it would not be like that. A menu confessionnel would be prepared with the greatest of care. But MBS has a bit more power than a kid called Mohammed in Seine Saint Denis.

At the same time

Hard to believe, yet this targeting of Muslim food as a danger to public order was actually the first of the measures outlined in his speech on 2 October, long heralded as the moment when he would reveal his action plan to deal with “separatisms” which became instead a drive against “Islamist separatism” dressed in language that opened a door to wider prejudices.

Macron did say – because there is with him always the careful “at the same time” so he can claim to be balanced and unprejudiced – that France had allowed the creation of ghettos but now had “to act so that the Republic can enter back into the reality of people’s lives” and “ensure a republican presence before every tower block”.

Equality of opportunity was a must, but his solution was a combination of tinkering with the crisis of schooling in the deprived suburbs like Seine-Saint-Denis – and the ineffective programme of “actor testing” to reveal discrimination in jobs and housing.

Back in 2003 a commission appointed by President Chirac reported on the same issues picked up by Macron. It plumped in favour of banning the hijab in schools but it said that measures such as that would not be understood or accepted by those against whom they were targeted unless something else was done as well.

“Secularism is not a familiar notion for many of our citizens. If it is necessary to promote secularism, that will only be seen as legitimate if the public authorities and the whole of society campaign against discriminatory practices and in favour of equality of opportunity.”

France got the ban on the hijab but not the campaign. Seventeen years on, the situation is worse, as Macron implicitly recognised. But the problem for official France is that dealing effectively with discrimination would show that the real issue is not Mohammed from Seine-Saint-Denis asking for an omelette let alone a chicken tagine with apricots and almonds, it is the structures of disadvantage and discrimination that the French state continues to protect.

Structures of disadvantage and discrimination

Like for instance that Catholic church in Aups with its secular, republican declaration over its entrance. When the law making France a secular state was voted in 1905, all such buildings became public property, their maintenance a public charge. Religious buildings built after that date, such as mosques, remain private property, their maintenance at the charge of the believers and no one else. Far from the biggest issue, but an illustration of the complex web that Macron exploits to his political advantage while refusing to mount that “campaign against discriminatory practices”.

Instead, France continues to drift into deeper social separation and ever more dangerous political waters. The day after the knife attack at the old offices of Charlie Hebdo, a morning presenter on FranceInfo, one of the main public news stations in French radio, had a little slip of the tongue. They spoke of terrorisme islamique [Islamic terrorism] rather than terrorisme islamiste [fundamentalist terrorism]. Neither they, nor anyone else on the programme, corrected the “mistake”. Why would they? The Interior Minister, Gérald Darmanin, himself did the same, alternating between the two formulas when speaking about the event later that very day.

They spoke of terrorisme islamique rather than terrorisme islamiste.

Back sometime around the turn of the millennium, the Met ran a series of advertising hoardings around London showing a Black guy in ordinary clothes running through a street. The idea was to see if the stereotype prompted in your mind was of a “mugger” rather than what the text then explained was supposedly the case, a detective chasing a suspect.

Not sure how many Black staff there actually were then in the Met’s CID units, but, in the minutes immediately after the Paris attack, a certain Youssef got a quick lesson about the stereotypes that plague the minds of police in Paris.

He tried to catch the assailant who slashed and hacked at two random journalists thinking he was attacking the Satan of Charlie Hebdo. He was there on CCTV running after him and was promptly given ten hours interrogation in a commissariat as the reward for his bravery, doing his time even as politicians and commentators were queuing up on the airwaves to intone against “l’amalgame”, the stereotype that all who are islamique [Muslim] are actually islamiste [devotees of political Islam]. The police had found their video evidence on his attempted citizen’s arrest “troubling”. The only trouble was in their own perverted minds.

La Haine, 1995. | Screenshot:YouTube.

Maquan in his descriptions of the lower orders who gave their lives in defence of democracy was obsessed with the way the women behaved and dressed. They had to be constrained and controlled those women in red, pistols at their belts, supposedly hard at work in the field canteen at Aups in December 1851.

And that Maquan of today, Gérald Darmanin? One had barely finished contemplating Macron’s speech before he was there in the National Assembly denouncing a left Deputy who had dared to suggest that the President was tilting at a non-existent windmill in order to avoid the real economic, social and viral crisis facing France:

“The situation is extremely grave and I cannot explain how a party like yours, which has for so long denounced the opium of the people, is linked to an Islamo-Leftism which is destroying the Republic.”

Chris Myant started as a journalist in 1968 working for the Morning Star and then 7Days. He later worked for the Commission for Racial Equality and Equality and Human Rights Commission. For the last decade he has lived in Paris where he is active in the National Union of Journalists.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved