By Robert Speel | –

No matter the outcome of the presidential election, it seems likely that Democrats and Republicans will end up in court.

President Trump has said he’s going to contest the election results – going so far as to say that he believes the election will ultimately be decided by the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has a team of lawyers lined up for a legal battle.

Unprecedented changes in voting procedures due to the coronavirus pandemic have created openings for candidates to cry foul. Republicans have argued that extending deadlines to receive and count ballots will lead to confusion and fraud, while Democrats believe Republicans are actively working to disenfranchise voters.

Should either candidate refuse to concede, it wouldn’t be the first time turmoil and claims of fraud dominated the days and weeks after the elections.

The elections of 1876, 1888, 1960 and 2000 were among the most contentious in American history. In each case, the losing candidate and party dealt with the disputed results differently.

1876: A compromise that came at a price

By 1876 – 11 years after the end of the Civil War – all the Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and Reconstruction was in full swing. The Republicans were strongest in the pro-Union areas of the North and African-American regions of the South, while Democratic support coalesced around southern whites and northern areas that had been less supportive of the Civil War. That year, Republicans nominated Ohio Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes, and Democrats chose New York Gov. Samuel Tilden.

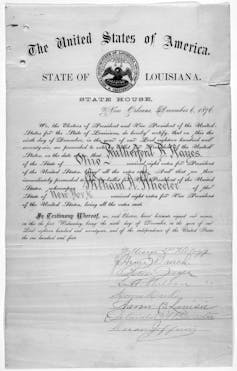

But on Election Day, there was widespread voter intimidation against African-American Republican voters throughout the South. Three of those Southern states – Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina – had Republican-dominated election boards. In those three states, some initial results seemed to indicate Tilden victories. But due to widespread allegations of intimidation and fraud, the election boards invalidated enough votes to give the states – and their electoral votes – to Hayes. With the electoral votes from all three states, Hayes would win a 185-184 majority in the Electoral College.

Wikimedia Commons

Competing sets of election returns and electoral votes were sent to Congress to be counted in January 1877, so Congress voted to create a bipartisan commission of 15 members of Congress and Supreme Court justices to determine how to allocate the electors from the three disputed states. Seven commissioners were to be Republican, seven were to be Democrats, and there would be one independent, Justice David Davis of Illinois.

But in a political scheme that backfired, Davis was chosen by Democrats in the Illinois state legislature to serve in the U.S. Senate. (Senators weren’t chosen by voters until 1913.) They’d hoped to win his support on the electoral commission. Instead, Davis resigned from the commission and was replaced by Republican Justice Joseph Bradley, who proceeded to join an 8-7 Republican majority that awarded all the disputed electoral votes to Hayes.

Democrats decided not to argue with that final result due to the “Compromise of 1877,” in which Republicans, in return for getting Hayes in the White House, agreed to an end to Reconstruction and military occupation of the South.

Hayes had an ineffective, one-term presidency, while the compromise ended up destroying any semblance of African-American political clout in the South. For the next century, southern legislatures, free from northern supervision, would implement laws discriminating against blacks and restricting their ability to vote.

1888: Bribing blocks of five

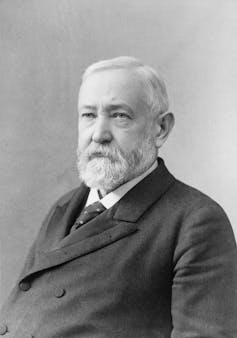

In 1888, Democratic President Grover Cleveland of New York ran for reelection against former Indiana U.S. Sen. Benjamin Harrison.

Back then, election ballots in most states were printed, distributed by political parties and cast publicly. Certain voters, known as “floaters,” were known to sell their votes to willing buyers.

Wikimedia Commons

Harrison had appointed an Indiana lawyer, William Wade Dudley, as treasurer of the Republican National Committee. Shortly before the election, Dudley sent a letter to Republican local leaders in Indiana with promised funds and instructions for how to divide receptive voters into “blocks of five” to receive bribes in exchange for voting the Republican ticket. The instructions outlined how each Republican activist would be responsible for five of these “floaters.”

Democrats got a copy of the letter and publicized it widely in the days leading up to the election. Harrison ended up winning Indiana by only about 2,000 votes but still would have won in the Electoral College without the state.

Cleveland actually won the national popular vote by almost 100,000 votes. But he lost his home state, New York, by about 1 percent of the vote, putting Harrison over the top in the Electoral College. Cleveland’s loss in New York may have also been related to vote-buying schemes.

Cleveland did not contest the Electoral College outcome and won a rematch against Harrison four years later, becoming the only president to serve nonconsecutive terms of office. Meanwhile, the blocks-of-five scandal led to the nationwide adoption of secret ballots for voting.

1960: Did the Daley machine deliver?

The 1960 election pitted Republican Vice President Richard Nixon against Democratic U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy.

The popular vote was the closest of the 20th century, with Kennedy defeating Nixon by only about 100,000 votes – a less than 0.2 percent difference.

Because of that national spread – and because Kennedy officially defeated Nixon by less than 1 percent in five states (Hawaii, Illinois, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico) and less than 2 percent in Texas – many Republicans cried foul. They fixated on two places in particular – southern Texas and Chicago, where a political machine led by Mayor Richard Daley allegedly churned out just enough votes to give Kennedy the state of Illinois. If Nixon had won Texas and Illinois, he would have had an Electoral College majority.

While Republican-leaning newspapers proceeded to investigate and conclude that voter fraud had occurred in both states, Nixon did not contest the results. Following the example of Cleveland in 1892, Nixon ran for president again in 1968 and won.

2000: The hanging chads

In 2000, many states were still using the punch card ballot, a voting system created in the 1960s. Even though these ballots had a long history of machine malfunctions and missed votes, no one seemed to know or care – until all Americans suddenly realized that the outdated technology had created a problem in Florida.

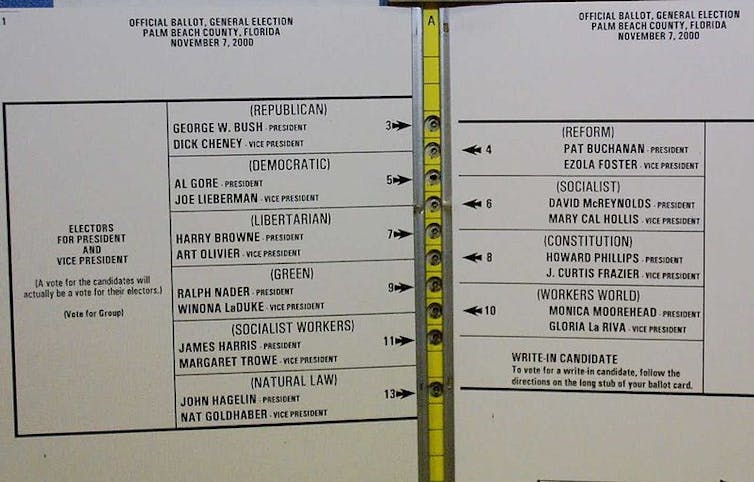

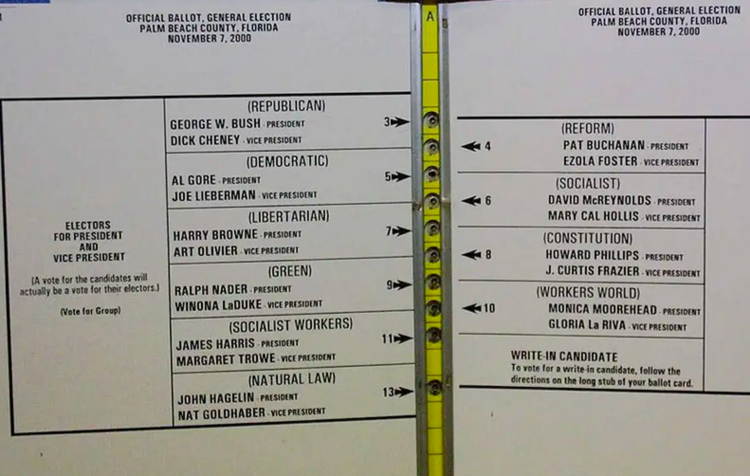

Then, on Election Day, the national media discovered that a “butterfly ballot,” a punch card ballot with a design that violated Florida state law, had confused thousands of voters in Palm Beach County.

Wikimedia Commons

Many who had thought they were voting for Gore unknowingly voted for another candidate or voted for two candidates. (For example, Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan received about 3,000 votes from voters who had probably intended to vote for Gore.) Gore ended up losing the state to Bush by 537 votes – and, in losing Florida, lost the election.

But ultimately, the month-long process to determine the winner of the presidential election came down to an issue of “hanging chads.”

Over 60,000 ballots in Florida, most of them on punch cards, had registered no vote for president on the punch card readers. But on many of the punch cards, the little pieces of paper that get punched out when someone votes – known as chads – were still hanging by one, two or three corners and had gone uncounted. Gore went to court to have those ballots counted by hand to try to determine voter intent, as allowed by state law. Bush fought Gore’s request in court. While Gore won in the Florida State Supreme Court, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled at 10 p.m. on Dec. 12 that Congress had set a deadline of that date for states to choose electors, so there was no more time to count votes.

Gore conceded the next day.

The national drama and trauma that followed Election Day in 1876 and 2000 could be repeated this year. Of course, a lot will depend on the margins and how the candidates react.

Most eyes will be on Trump, who hasn’t said whether or not he’ll accept the result if he loses.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Nov. 1, 2016.

Robert Speel, Associate Professor of Political Science, Erie campus, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved