Southwest Harbor, Maine (Special to Informed Comment) – The United States is engaged in forever hot wars. The war in Afghanistan now nears the end of its second decade. Why US history is so saturated -— some would say polluted -— by war has recently become an object of both academic and activist interest.

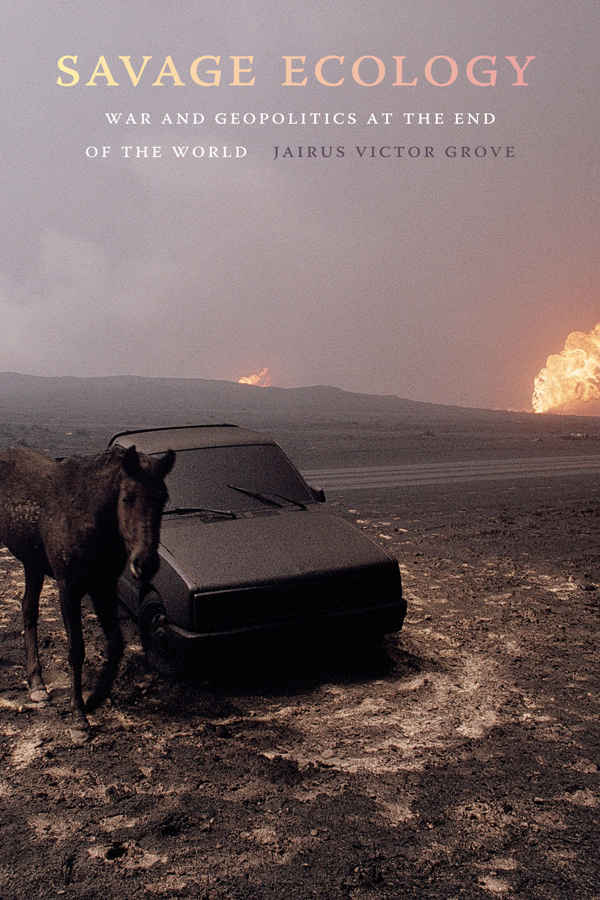

University of Hawaii at Manoa International Relations theorist Jairus Victor Grove poses this question in his

Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World.

He asks why US citizens are not waging another possible war, global climate change.

If humanity faces so grave a crisis– now almost universally recognized–why does the citizenry not unite in defense of survival?

The problem is that there is no we as such. Those who pollute or poison the most are seldom the victims of this degradation while those who contribute the least suffer the most damage but are too powerless to protest effectively. These asymmetries prevail on both a domestic and international levels . As does denial of this inequality I can’t count the number of times since the beginning of the pandemic I have heard: ”We are all in this together.”.

Both domestic and international arenas fall far short of the equality celebrated by Rousseau, communities where none are too impoverished or powerless to participate in common decisions and none are too wealthy to escape needs for common resources.

Far from a community or polity in a classic sense this is an era of geopolitics. This is a form of life” that pursues a savage ecology radically antagonistic to survival as a collective rather than discriminatory goal.”

Geopolitics is not an overriding cause that can explain all the major developments of our era in the way some Marxists attribute unitary causality to the means of production . Geopolitics is ‘a means that has been elevated and refined into a virtue. Because it is a virtue it succeeds and fails without much consideration as to whether it should be abandoned.”

What would it mean to consider warfare as a form of life, an ordinary practice for most people rather than characterizing war as an anomalous event carried on by a narrow subset of the population? Warfare in this view is something other and more than conflict between or among bounded and delineated or preformed states. What if the normal workings of daily life are a state of war? In this context Grove is using state of war in the same way a chemist would employ states of matter.

Imagine a block of ice. That block is in solid state but nonetheless contains some molecules that are liquid and even gaseous. Though the block contains heterogeneous components, all are affected by the general state of solidity. Grove argues that the state of war intensifies the field of relations that make the world what it is today. “The practices and organizations—from resource extraction, enclosure, carbon liberalization, racialization, mass incarceration, primitive accumulation by dispossession, targeted trikes to all out combat are relations of war rather than opportunities for a war metaphor.”

These relations can be seen as resonating with each other and intensifying and being energized by the state of war. War does not replace other grand theories or explanation of ecological crisis but is interrelated with and most importantly seni-autonomous. Grove correctly argues given the level of violence needed to create the current order it is not a stretch to “call war part of the constitutive practices of planetary relations” and one often issuing in phase shifts such as the conversion of intense racial prejudice to all out race wars.

Grove’s provocative discussion of the state of war is an instance of the ecological perspective informing and sustained by the entire work : Human and nonhuman entities coevolve in complex and often unpredictable ways that belie ideals of a predictable, causal social and even natural science..

Grove further explicates his thesis by presenting the role that genocide has played in state formation and the centrality of war to the industrial revolution.

Grove maintains that war as an intensive difference filters into and revises other categories and oppositions.

To his examples I would only add international trade as a field once thought to be a guarantor of peace but now a growing recipient and intensifier of ethnic, national and class antagonisms. Workers are bounded by heavily policed boundaries even as capital is free to migrate. In a geopolitical climate this is a recipe for xenophobia or worse, as both the Americas and the Eurozone amply demonstrate today.

The 500-year geopolitical enterprise since the age of Columbus, from settler colonialism to the IMF and the Washington consensus has brought with it a homogenization or attempt thereof for the whole globe.

Will this savage ecology take us with it? Grove emphasizes a side of the story given little emphasis by most of the climate crisis radicals.

- “Irreversible catastrophic changes are certain but extinction is unlikely. What we stand to lose as a species in this current apocalypse of homogenization is unimaginable , not because of the loss of life but because of the loss of difference. Who and what will be left on Earth to inspire and ally with us in our creative advance is uncertain. If the future is dominated by those who seek to establish the survival of the human species at all costs through technological mastery then whatever “we” manages to persist will likely live on or near a mean and lonely planet.”(209)

Rejecting the ugly blend of geopolitics and neoliberalism is not enough. From the basis of a geopolitical world and a savage ecology —- a world that does not care about us -— he constructs suggestions for the practice of International Relations Theory (IR) and a broader ethic for the political activists. The former would challenge social science’s futile quest for laws and predictions in favor of broadening how much of the world we could experience and be a part of. Toward this end he advances an ethics that “is defined as a means to intervene in the vitality of becoming, not to steer its course as captains of our destiny but as attempts to drag our feet in the water in hopes of going productively off course.” (232)

Tragedy is inevitable, but also paradoxically it is the basis of our freedom. A world governed by law or inner purpose is a world without the precondition of freedom for humans or other creatures. An apocalypse is more and less than an extinction. Whole evolutionary lines may be destroyed, but other new emergents often follow. Grove welcomes artificial intelligence and robots. Human beings can hardly object, given all the harm they have done.

In an oddly provocative manner Jairus Victor Grove has provided an eloquent and impassioned tribute to war and its savage ecology. This book is a twofer, a thoughtful intervention in current policy debate and a scorching critique of mainstream IR theory, with its arrogant pretensions and its plenitude of crucial failures and catastrophic consequences. It will be tragic if activists and the discipline’s leading practitioners fail to read it.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved