By Matthew Ward | –

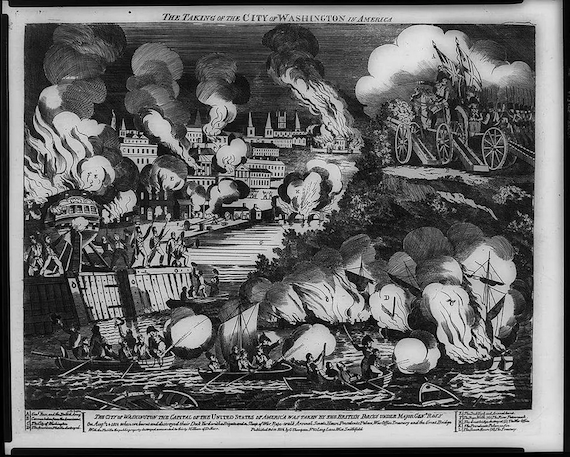

As rioters forced their way into the US Capitol Building on January 6, astounded CNN presenters noted that this was the first time something like this had happened for more than 200 years. And that on the occasion it was the British, an enemy power, which was responsible.

This was in August 1814 when British troops led by General Robert Ross occupied Washington DC for two days and set about methodically destroying the city’s public buildings, including the Capitol and the White House.

The War of 1812 had been underway for two years. It was a war the British had not sought. For the British its roots lay in debates over maritime rights, which had been conceded on the eve of the conflict, but news of these concessions only arrived across the Atlantic after the United States had declared war.

American politicians expected to win quickly, and many hoped that they could also conquer British Canada. The Americans burned several Canadian towns including the upper Canadian capital of York, now Toronto, but the war remained a stalemate.

By the spring of 1814, the Napoleonic Wars in Europe had ended. On March 30, the Russians had entered Paris and Napoleon had gone into exile. At last, the British felt that they could turn their attention to the war with the United States.

It would take time to send troops from Europe, but in the summer of 1814 the British possessed naval superiority. They used this to devastating effect in the Chesapeake Bay, raiding tobacco plantations and encouraging the enslaved population to join the struggle. So great was the fear of a potential slave uprising that many of the militia who might have been protecting the capital were posted nearer their homes.

In August 1814, a British naval force commanded by Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cockburn sailed up the Patuxent River in the northern Chesapeake Bay and landed 4,500 men near the village of Benedict in Maryland.

It was not initially clear where the British intended to attack. Washington was only 30 miles away, but it was not strategically important, and little had been done to erect defences. American forces made a dismal attempt to halt the advance at Bladensburg, where the British had to cross the eastern branch of the Potomac River. So many American militiamen fled the field of battle that British troops called the affair the Bladensburg Races, and from that point they met only scattered resistance.

There was now widespread panic in Washington. The president’s wife, Dolly Madison, hastily organised the evacuation of the most important items in the President’s House, not yet called the White House. So hasty was the evacuation that when British troops arrived, they found dinner waiting.

Terrible spectacle

As British troops advanced into Capitol Square, they met scattered sniper fire. Firing several rounds into the Capitol building to discourage the snipers, they forced their way inside with little difficulty. The men were impressed by the grandeur of the interior. It was not what they expected but was of imposing proportions with high ceilings and classical columns, Americanised with carvings of ears of corn decorating the capitals, while the well-proportioned rooms were filled with fine furnishings.

It also proved more difficult to burn than they expected – the roof was iron and the floors and walls were stone. The troops busied themselves piling up all the furniture, books and papers and eventually started a blaze which lit the night sky over the city.

Upon seeing the flames, the French minister to the US, Louis Sérurier observed: “I have never beheld a spectacle more terrible and at the same time more magnificent.” Most of the interior was completely gutted. The heat was so intense that in places the stone columns and floor were turned to lime, and the roof collapsed.

George Munger/US Library of Congress

Not content with destroying the Capitol, the British burned the President’s House. (Despite the legend it is not called the White House because it was painted white to hide the scorch marks.)

The most infamous act was probably the destruction of the Library of Congress and all of its papers and books. British commanders ordered their men to target only public buildings and spare private buildings and the US Patent Office and many Washington residents later commended their restraint.

But at the printing office of the National Intelligencer newspaper, in an episode not dissimilar from turning off a Twitter account, Admiral Cockburn ordered his men to destroy all the letter C’s so the newspaper could no longer print what he saw as their lies about him.

Pyrrhic victory

After two days, the British force withdrew. The burning of Washington was symbolic rather than strategic for it had a population of only 8,000 and the long-term disruption to the government was minimal. Perhaps the most significant strategic loss for the United States was the destruction of the Washington Navy Yard and several ships under construction. This was not done by British troops, however, but by American forces on the Navy secretary’s orders to prevent the enemy from capturing important supplies.

William Thornton/Library of Congress

In many ways, the burning of Washington backfired on the British as it created much sympathy for the American cause in Europe. The burning of the public buildings also achieved little in the long-term.

The Capitol survived. Its design was extremely resilient, and the structure remained intact. After only five years of reconstruction, Congress was again able to hold its meetings there.

Matthew Ward, Senior Lecturer in History, University of Dundee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image: The taking of the city of Washington in America, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved