From the American Revolution through the Global War on Terror, author Chris Lombardi tells the inspiring stories of people who refused to kill.

By Frida Berrigan | –

( Waging Nonviolence) – Everywhere I look, violence is the answer. Geopolitics and foreign policy, criminal justice and incarceration, education and housing policy, entertainment — especially entertainment. The guns are so seductive. The violence is so addictive, at least when it is in high-definition and packaged as entertainment. It goes down as easy as salty chips.

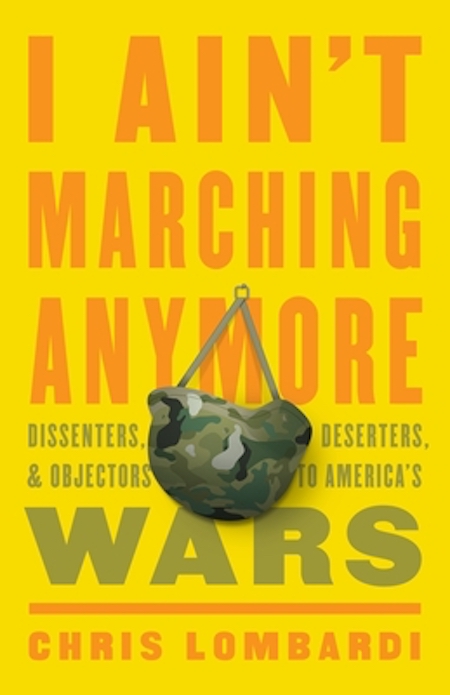

After reading Chris Lombardi’s epic new book “I Ain’t Marching Anymore: Dissenters, Deserters and Objectors to America’s Wars,” I felt compelled to count the deaths I witnessed on a nightly basis. My husband and I recently got stuck in “Altered Carbon” — a confusing but watchable future dystopian who-dunnit — and in one 40-minute episode, we saw more than 100 people die. Until I counted, I hadn’t really been conscious of the ways I had been enjoying the carnage. Then I felt sick and manipulated and pressed the pause button.

The real life characters in Lombardi’s book watch people die too, but they aren’t doing it for fun. They are stuck in the midst of real wars and forced to confront their own humanity and the visceral, undeniable humanity of those on the other side of the battlefield. What is striking and uplifting about this densely researched book is how often, and how naturally, people rediscover or unearth their humanity by refusing to kill and organizing against war. Thankfully, Lombardi’s granular, human-sized history of armed conflict — and the people who put their guns down — is truly satisfying food for the heart and soul in this difficult and frightening time.

Lombardi starts with the American revolution and moves chronologically through U.S. history, telling 260 years of stories of resisters, organizers and conscientious objectors from the American Revolution through the Global War on Terror. A cursory and superficial examination of U.S. war history might pause on the Quaker’s conscientious objection or Muhammed Ali heading off to prison instead of Vietnam, but Lombardi offers tightly embroidered instances of dissent, resistance and conscience in every war the United States has fought.

As I read, I kept trying to imagine the piles of papers on Lombardi’s desk. Her notes take up more than 30 pages and she references hundreds of first-hand accounts — diaries, letters, newspaper articles and unpublished memoirs in order to ensure that the stories of war and war resisters are told in their own words. What’s more, she shows how one act of resistance sparks additional acts — and how one generation inspires the next. This must be why we don’t learn these stories in school.

Lombardi’s book provokes the question: Who gets to be a hero? The victors and the war makers stand on every plinth and pedestal and glower from the town squares. Meanwhile, names like William Apess and Susan Schnall are barely known: These human beings trained as fighters who clung to their humanity, as well as the belief that the only way to survive is to ensure that no one else sees what they saw, smells what they smelled or perpetrates what they were forced to perpetrate.

Throughout “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” Lombardi weaves a tapestry of interconnection, mutual inspiration and motivation. She centers the voices and experiences of women, African Americans, Native Americans and recent immigrants. Again and again, these marginalized people experienced war — fought, suffered and cared for the wounded and buried the dead. They were forever changed by their harrowing experiences. And so, they resisted war and violence and worked to ensure that those conscripted to fight the nation’s wars were taken care of in the aftermath.

While reading the book, I kept highlighted every unfamiliar name. These are just a few that stood out:

- Jacob Ritter, a Revolutionary War soldier from a Lutheran family, did not fire his musket in the Battle of Brandywine. Instead he prayed that God deliver him “from shedding the blood of my fellow creatures that day, I would never fight again.” He kept his promise, fleeing the battle and hiding until he was arrested by the British and held in their prison in Philadelphia. He joined the Quakers after his prison ordeal and worked against war making for the rest of his life.

- William Apess, an African-American Pequot boy from Massachusetts, was plied with alcohol by military recruiters and illegally signed up for the Army despite his status as a minor and an indentured servant at just 15. Apess experienced the brutality of the War of 1812 and went on to serve the cause of Native American rights as a Methodist preacher, organizer and sought-after orator. He said, “Does it not appear that the cause of all wars was and is that the whites have always been the aggressors and the wars, cruelties and bloodshed is a job of their own making and not the Indians.”

- Jackie Robinson, who went on to integrate Major League Baseball, was courtmartialed as a young lieutenant when he refused to go to the back of an interstate bus in 1944.

- Clarence Adams, an 18-year-old African American, who wanted to be a boxer, enlisted in the Army in Memphis. He was sent to Korea, and all but 10 men from his unit were killed before he was captured by the North Koreans and marched North. Once he was freed three years later, he decided to stay in China rather than return to the Jim Crow south. Adams settled in China, went to university, started a family, hosted W.E.B. DuBois and worked for Radio Hanoi. In one broadcast, he reached out to Black troops, telling them, “You are supposedly fighting for freedom of the Vietnamese, but what kind of freedom do you have at home… Go home and fight for equality in America.” Adams lived in China for 14 years until the Cultural Revolution made life difficult, and he brought his family home to Memphis.

- Susan Schnall, a Navy Nurse, dropped anti-war posters all over the West Coast in a rented plane to advertise the first GI and Veterans March for Peace in October 1968 through San Francisco. Four hundred soldiers and 10,000 civilians marched behind Schnall and the friends she recruited with her airdropped posters. She was convicted of “conduct unbecoming an officer” and spent four months in the brig in Oakland.

I learned so much of my history — our history — reading Lombardi’s book and only missed one story that could have been included: World War I resister Ben Salmon. This Catholic farmer with an 8th grade education was sentenced to life in prison after refusing induction on the grounds of his faith. He spent three years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement, for refusing to work while in prison. Still there after the war ended, Salmon was committed to an insane asylum, where he wrote a 229-page justification for his refusal to participate in war-making. In it, he asserts, “Either Jesus was a liar or war is never necessary.”

He was one of four Catholic conscientious objectors to the Great War who all suffered disproportionately because of the Vatican’s blessing on “just wars.” Ben Salmon died at the age of 43, his health destroyed by his time in prison. But his memory lives on. Two of his three children entered religious life, and there is a movement to shed more light on his writings, his example and his lived faith.

Lombardi’s book begins with Jacob Ritter in a blood-soaked field at the Battle of Brandywine, not too far from Philadelphia. It ends with accounts of young people resisting militarism from within the military in the aftermath of Sept. 11. Jennifer Hoag, a National Guardswoman called to active duty after 9/11, recalled not feeling comfortable hugging or kissing her girlfriend goodbye. That discomfort led to more questions: “What freedom could we offer to the world if we treat it so restricted based on who a person falls in love with?” She felt moved to join anti-war actions in the early days of the Bush administration’s war in Iraq in 2003. “I knew that there was something not right about this unfolding appetite for destruction… I took a stand against the war in Iraq and it was not even 24 hours old.” The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq morphed into the Global War on Terror and nearly two decades later, they grind on still. The technology of war has developed and advanced in the last two and a half centuries as war planners attempt to circumvent and short circuit conscience. But military personnel are still gripped by conscience just as Jacob Ritter was 1777.

Reading Lombardi’s book has been a balm. Her story reconnects me to the strong spirit of dissent, resistance and organizing that has always run through our history (but is seldom found on TV or Netflix). Her book reminds me that the spirit that animated Ritter, Apess, Schnall and their more recent counterparts is still pulsing and robust. What a relief — because we need it now more than ever!

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved