By Jordan Brasher | –

Confederate soldiers never reached the Capitol during the Civil War. But the Confederate battle flag was flown by rioters in the U.S. Capitol building for the first time ever on Jan. 6.

The flag’s prominence in the Capitol riot comes as no surprise to those who, like me, know its history: Since its debut during the Civil War, the Confederate battle flag has been flown regularly by white insurrectionists and reactionaries fighting against rising tides of newly won Black political power.

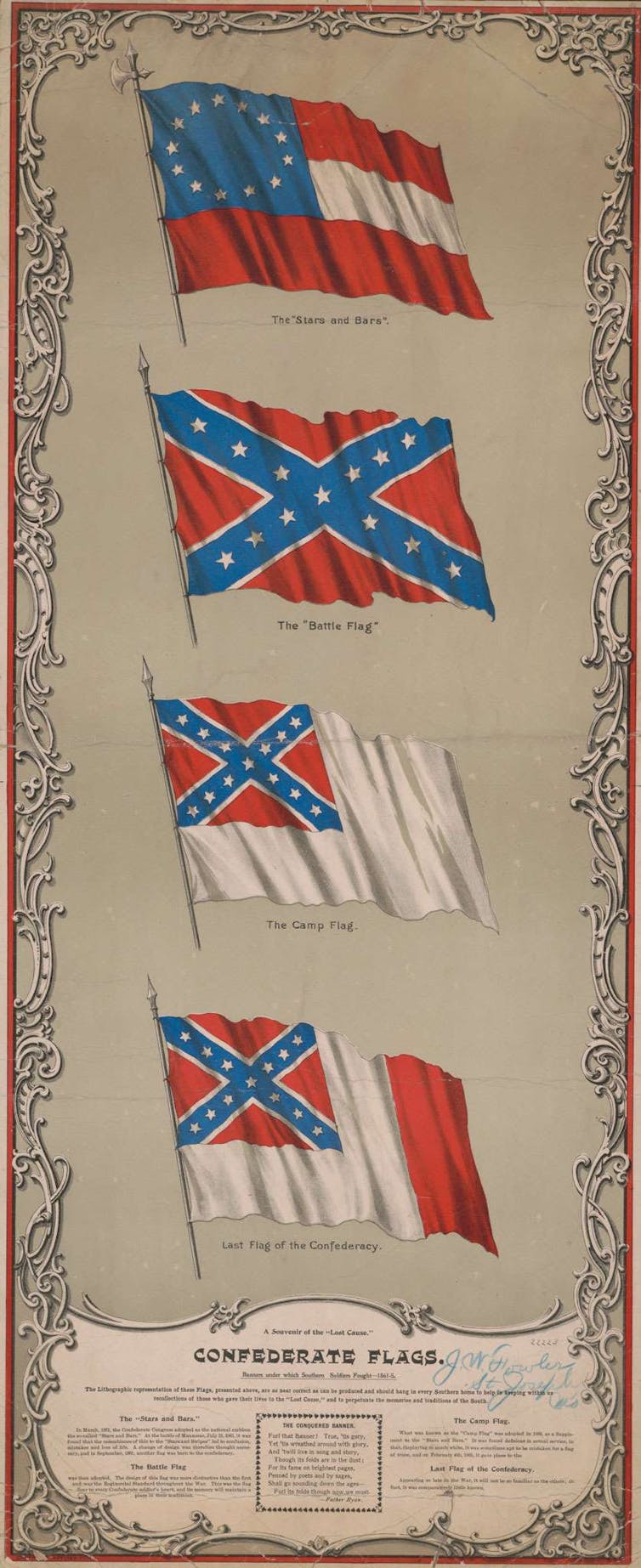

Library of Congress via National Geographic

The infamous diagonal blue cross with white stars on a red background was never the Confederacy’s official symbol. The Confederacy’s original “stars and bars” design was too similar to the U.S. flag, which led to confusion on the battlefields, where troop positions were marked by flags.

The official flag went through a series of changes in attempts to distinguish Confederate from Union troops. The Confederacy would ultimately adopt the “Southern Cross” as its battle flag – cementing it as a symbol of white insurrection. While it is technically the battle flag, it has been used the most, and therefore has become known more generally as the Confederate flag.

Kurz and Allison, restoration by Adam Cuerden, via Wikimedia Commons

The original emblem

Six decades before the Nazi swastika became an instantly recognizable symbol of white supremacists, the Confederate battle flag flew over the forces of the insurgent Confederate States of America – military troops organized in revolt against the idea that the federal government could outlaw slavery.

The founding documents of the Confederacy make its goals of white supremacy and preservation of slavery explicitly clear. In March 1861, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens declared of the Confederacy, “its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

The documents drafted by seceding states make this same point. Mississippi’s declaration, for instance, was very specific: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world.”

Backlash against racial integration

After the Civil War, Confederate veterans groups used the flag at their meetings to commemorate fallen soldiers, but otherwise the flag mostly disappeared from public life.

After World War II, though, the flag surfaced as part of a backlash against racial integration.

Black soldiers who fought discrimination abroad experienced discrimination when they came home. Racist violence against Black veterans who had returned from battle prompted President Harry Truman to issue an executive order desegregating the military and banning discrimination in federal hiring. Truman also asked Congress to pass a federal ban on lynching, one of nearly 200 unsuccessful attempts to do so.

In 1948, the retaliation for Truman’s integration efforts came, and the Confederate battle flag resurfaced as a symbol of white supremacist public intimidation.

That year, U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, a South Carolina Democrat, ran for president as the leader of a new political party of segregationist Southern Democrats, nicknamed the “Dixiecrats.” At their rallies and riots, they opposed Truman’s integration under the banner of the Confederate battle flag.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, white Southerners flew the Confederate battle flag at riots – including violent ones – to oppose racial integration, especially in schools. For example, in 1962, white students at the University of Mississippi hoisted it at a riot defying James Meredith’s enrollment as the university’s first Black student.

It took the deployment of 30,000 U.S. troops, federal marshals and National Guardsmen to get Meredith to class after the violent race riot left two dead. Historian William Doyle called the riot – which featured the Confederate battle flag at its center – an “American insurrection.”

Charleston, Charlottesville and the Capitol

More recently, the Black Lives Matter era has seen an increase in violent incidents involving the Confederate battle flag. It has now featured prominently in at least three recent major violent events carried out by people on the far right.

In 2015, a white supremacist who had posed with the Confederate battle flag online killed nine Black parishioners during a prayer meeting at their church.

In 2017, neo-Nazis and other white supremacists carried the battle flag when they marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, seeking to prevent the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. One white supremacist drove his car through a crowd of anti-racist counterprotestors, killing Heather Heyer.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

At the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, an image of an insurrectionist toting the Confederate battle flag inside the Capitol building arguably distills the siege’s dark historical context. In the background of the photo are the portraits of two Civil War-era U.S. senators – one an ardent proponent of slavery and the other an abolitionist once beaten unconscious for his views on the Senate floor.

The flag has always represented white resistance to increasing Black power. It may be a coincidence of exact timing, but certainly not of context, that the riot happened the day after Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff won U.S. Senate seats representing Georgia. Respectively, they are the first Black and first Jewish senators from the former Confederate state. Warnock will be only the second Black senator from below the Mason-Dixon Line since Reconstruction.

Their historic victories – and President-elect Joe Biden’s – in Georgia happened through large-scale organizing and turnout of people of color, especially Black people. Since 2014, nearly 2 million voters have been added to the rolls in Georgia, signaling a new bloc of Black voting power.

It should come as no surprise, then, that today’s white insurrectionists opposed to the shifting tides of power identify with the Confederate battle flag.

Jordan Brasher, Assistant Professor of Geography, Columbus State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

—–

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved