( Tomdispatch.com ) – How can you tell when your empire is crumbling? Some signs are actually visible from my own front window here in San Francisco.

Directly across the street, I can see a collection of tarps and poles (along with one of my own garbage cans) that were used to construct a makeshift home on the sidewalk. Beside that edifice stands a wooden cross decorated with a string of white Christmas lights and a red ribbon — a memorial to the woman who built that structure and died inside it earlier this week. We don’t know — and probably never will — what killed her: the pandemic raging across California? A heart attack? An overdose of heroin or fentanyl?

Behind her home and similar ones is a chain-link fence surrounding the empty playground of the Horace Mann/Buena Vista elementary and middle school. Like that home, the school, too, is now empty, closed because of the pandemic. I don’t know where the families of the 20 children who attended that school and lived in one of its gyms as an alternative to the streets have gone. They used to eat breakfast and dinner there every day, served on the same sidewalk by a pair of older Latina women who apparently had a contract from the school district to cook for the families using that school-cum-shelter. I don’t know, either, what any of them are now doing for money or food.

Just down the block, I can see the line of people that has formed every weekday since early December. Masked and socially distanced, they wait patiently to cross the street, one at a time, for a Covid test at a center run by the San Francisco Department of Health. My little street seems an odd choice for such a service, since — especially now that the school has closed — it gets little foot traffic. Indeed, a representative of the Latino Task Force, an organization created to inform the city’s Latinx population about Covid resources told our neighborhood paper Mission Local that

“Small public health clinics such as this one ‘will say they want to do more outreach, but I actually think they don’t want to.’ He believes they chose a low-trafficked street like Bartlett to stay under the radar. ‘They don’t want to blow the spot up, because it does not have a large capacity.’”

What do any of these very local sights have to do with a crumbling empire? They’re signs that some of the same factors that fractured the Roman empire back in 476 CE (and others since) are distinctly present in this country today — even in California, one of its richest states. I’m talking about phenomena like gross economic inequality; over-spending on military expansion; political corruption; deep cultural and political fissures; and, oh yes, the barbarians at the gates. I’ll turn to those factors in a moment, but first let me offer a brief defense of the very suggestion that U.S. imperialism and an American empire actually exist.

Imperialism? What’s That Supposed to Mean?

What better source for a definition of imperialism than the Encyclopedia Britannica, that compendium of knowledge first printed in 1768 in the country that became the great empire of the nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries? According to the Encyclopedia, “imperialism” denotes “state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas.” Furthermore, imperialism “always involves the use of power, whether military or economic or some subtler form.” In other words, the word indicates a country’s attempts to control and reap economic benefit from lands outside its borders.

In that context, “imperialism” is an accurate description of the trajectory of U.S. history, starting with the country’s expansion across North America, stealing territory and resources from Indian nations and decimating their populations. The newly independent United States would quickly expand, beginning with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase from France. That deal, which effectively doubled its territory, included most of what would become the state of Louisiana, together with some or all of the present-day states of New Mexico, Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, Montana, and even small parts of what are today the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Of course, France didn’t actually control most of that land, apart from the port city of New Orleans and its immediate environs. What Washington bought was the “right” to take the rest of that vast area from the native peoples who lived there, whether by treaty, population transfers, or wars of conquest and extermination. The first objective of that deal was to settle land on which to expand the already hugely lucrative cotton business, that economic engine of early American history fueled, of course, by slave labor. It then supplied raw materials to the rapidly industrializing textile industry of England, which drove that country’s own imperial expansion.

U.S. territorial expansion continued as, in 1819, Florida was acquired from Spain and, in 1845, Texas was forcibly annexed from Mexico (as well as various parts of California a year later). All of those acquisitions accorded with what newspaper editor John O’Sullivan would soon call the country’s manifest — that is, clear and obvious — destiny to control the entire continent.

Eventually, such expansionism escaped even those continental borders, as the country went on to gobble up the Philippines, Hawaii, the Panama Canal Zone, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the Mariana Islands, the last five of which remain U.S. territories to this day. (Inhabitants of the nation’s capital, where I grew up, were only partly right when we used to refer to Washington, D.C., as “the last colony.”)

American Doctrines from Monroe to Truman to (G.W.) Bush

U.S. economic, military, and political influence has long extended far beyond those internationally recognized possessions and various presidents have enunciated a series of “doctrines” to legitimate such an imperial reach.

Monroe: The first of these was the Monroe Doctrine, introduced in 1823 in President James Monroe’s penultimate State of the Union address. He warned the nations of Europe that, while the United States recognized existing colonial possessions in the Americas, it would not permit the establishment of any new ones.

President Teddy Roosevelt would later add a corollary to Monroe’s doctrine by establishing Washington’s right to intercede in any country in the Americas that, in the view of its leaders, was not being properly run. “Chronic wrongdoing,” he said in a 1904 message to Congress, “may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation.” The United States, he suggested, might find itself forced, “however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.” In the first quarter of the twentieth century, that Roosevelt Corollary would be used to justify U.S. occupations of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Nicaragua.

Truman: Teddy’s cousin, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, publicly renounced the Monroe Doctrine and promised a hands-off attitude towards Latin America, which came to be known as the Good Neighbor Policy. It didn’t last long, however. In a 1947 address to Congress, the next president, Harry S. Truman, laid out what came to be known as the Truman Doctrine, which would underlie the country’s foreign policy at least until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. It held that U.S. national security interests required the “containment” of existing Communist states and the prevention of the further spread of Communism anywhere on Earth.

It almost immediately led to interventions in the internal struggles of Greece and Turkey and would eventually underpin Washington’s support for dictators and repressive regimes from El Salvador to Indonesia. It would justify U.S.-backed coups in places like Iran, Guatemala, and Chile. It would lead this country into a futile war in Korea and a disastrous defeat in Vietnam.

That post-World War II turn to anticommunism would be accompanied by a new kind of colonialism. Rather than directly annexing territories to extract cheap labor and cheaper natural resources, under this new “neocolonial” model, the United States — and soon the great multilateral institutions of the post-war era, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund — would gain control over the economies of poor nations. In return for aid — or loans often pocketed by local elites and repaid by the poor — those nations would accede to demands for the “structural adjustment” of their economic systems: the privatization of public services like water and utilities and the defunding of human services like health and education, usually by American or multinational corporations. Such “adjustments,” in turn, allowed the recipients to service the loans, extracting scarce hard currency from already deeply impoverished nations.

Bush: You might have thought that the fall of the Soviet empire and the end of the Cold War would have provided Washington with an opportunity to step away from resource extraction and the seemingly endless military and CIA interventions that accompanied it. You might have imagined that the country then being referred to as the “last superpower” would finally consider establishing new and different relationships with the other countries on this little planet of ours. However, just in time to prevent even the faint possibility of any such conversion came the terrorist attacks of 9/11, which gave President George W. Bush the chance to promote his very own doctrine.

In a break from postwar multilateralism, the Bush Doctrine outlined the neoconservative belief that, as the only superpower in a now supposedly “unipolar” world, the United States had the right to take unilateral military action any time it believed it faced external threat of any imaginable sort. The result: almost 20 years of disastrous “forever wars” and a military-industrial complex deeply embedded in our national economy. Although Donald Trump’s foreign policy occasionally feinted in the direction of isolationism in its rejection of international treaties, protocols, and organizational responsibilities, it still proved itself a direct descendant of the Bush Doctrine. After all, it was Bush who first took the United States out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and rejected the Kyoto Protocol to fight climate change.

His doctrine instantly set the stage for the disastrous invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, the even more disastrous Iraq War, and the present-day over-expansion of the U.S. military presence, overt and covert, in practically every corner of the world. And now, to fulfill Donald Trump’s Star Trek fantasies, even in outer space.

An Empire in Decay

If you need proof that the last superpower, our very own empire, is indeed crumbling, consider the year we’ve just lived through, not to mention the first few weeks of 2021. I mentioned above some of the factors that contributed to the collapse of the famed Roman empire in the fifth century. It’s fair to say that some of those same things are now evident in twenty-first-century America. Here are four obvious candidates:

Grotesque Economic Inequality: Ever since President Ronald Reagan began the Republican Party’s long war on unions and working people, economic inequality has steadily increased in this country, punctuated by terrible shocks like the Great Recession of 2007-2008 and, of course, by the Covid-19 disaster. We’ve seen 40 years of tax reductions for the wealthy, stagnant wages for the rest of us (including a federal minimum wage that hasn’t changed since 2009), and attacks on programs like TANF (welfare) and SNAP (food stamps) that literally keep poor people alive.

The Romans relied on slave labor for basics like food and clothing. This country relies on super-exploited farm and food-factory workers, many of whom are unlikely to demand more or better because they came here without authorization. Our (extraordinarily cheap) clothes are mostly produced by exploited people in other countries.

The pandemic has only exposed what so many people already knew: that the lives of the millions of working poor in this country are growing ever more precarious and desperate. The gulf between rich and poor widens by the day to unprecedented levels. Indeed, as millions have descended into poverty since the pandemic began, the Guardian reports that this country’s 651 billionaires have increased their collective wealth by $1.1 trillion. That’s more than the $900 billion Congress appropriated for pandemic aid in the omnibus spending bill it passed at the end of December 2020.

An economy like ours, which depends so heavily on consumer spending, cannot survive the deep impoverishment of so many people. Those 651 billionaires are not going to buy enough toys to dig us out of this hole.

Wild Overspending on the Military: At the end of 2020, Congress overrode Trump’s veto of the annual National Defense Authorization Act, which provided a stunning $741 billion to the military this fiscal year. (That veto, by the way, wasn’t in response to the vast sums being appropriated in the midst of a devastating pandemic, but to the bill’s provisions for renaming military bases currently honoring Confederate generals, among other extraneous things.) A week later, Congress passed that omnibus pandemic spending bill and it contained an additional $696 billion for the Defense Department.

All that money for “security” might be justified, if it actually made our lives more secure. In fact, our federal priorities virtually take food out of the mouths of children to feed the maw of the military-industrial complex and the never-ending wars that go with it. Even before the pandemic, more than 10% of U.S. families regularly experienced food insecurity. Now, it’s a quarter of the population.

Corruption So Deep It Undermines the Political System: Suffice it to say that the man who came to Washington promising to “drain the swamp” has presided over one of the most corrupt administrations in U.S. history. Whether it’s been blatant self-dealing (like funneling government money to his own businesses); employing government resources to forward his reelection (including using the White House as a staging ground for parts of the Republican National Convention and his acceptance speech); tolerating corrupt subordinates like Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross; or contemplating a self-pardon, the Trump administration has set the bar high indeed for any future aspirants to the title of “most corrupt president.”

One problem with such corruption is that it undermines the legitimacy of government in the minds of the governed. It makes citizens less willing to obey laws, pay taxes, or act for the common good by, for example, wearing masks and socially distancing during a pandemic. It rips apart social cohesion from top to bottom.

Of course, Trump’s most dangerous corrupt behavior — one in which he’s been joined by the most prominent elected and appointed members of his government and much of his party — has been his campaign to reject the results of the 2020 general election. The concerted and cynical promotion of the big lie that the Democrats stole that election has so corrupted faith in the legitimacy of government that up to 68% of Republicans now believe the vote was rigged to elect Joe Biden. At “best,” Trump has set the stage for increased Republican suppression of the vote in communities of color. At worst, he has so poisoned the electoral process that a substantial minority of Americans will never again accept as free and fair an election in which their candidate loses.

A Country in Ever-Deepening Conflict: White supremacy has infected the entire history of this country, beginning with the near-extermination of its native peoples. The Constitution, while guaranteeing many rights to white men, proceeded to codify the enslavement of Africans and their descendants. In order to maintain that enslavement, the southern states seceded and fought a civil war. After a short-lived period of Reconstruction in which Black men were briefly enfranchised, white supremacy regained direct legal control in the South, and flourished in a de facto fashion in the rest of the country.

In 1858, two years before that civil war began, Abraham Lincoln addressed the Illinois Republican State Convention, reminding those present that

“‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

More than 160 years later, the United States clearly not only remains but has become ever more divided. If you doubt that the Civil War is still being fought today, look no farther than the Confederate battle flags proudly displayed by members of the insurrectionary mob that overran the Capitol on January 6th.

Oh, and the barbarians? They are not just at the gate; they have literally breached it, as we saw in Washington when they burst through the doors and windows of the center of government.

Building a Country From the Rubble of Empire

Human beings have long built new habitations quite literally from the rubble — the fallen stones and timbers — of earlier ones. Perhaps it’s time to think about what kind of a country this place — so rich in natural resources and human resourcefulness — might become if we were to take the stones and timbers of empire and construct a nation dedicated to the genuine security of all its people. Suppose we really chose, in the words of the preamble to the Constitution, “to promote the general welfare, and to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.”

Suppose we found a way to convert the desperate hunger for ever more, which is both the fuel of empires and the engine of their eventual destruction, into a new contentment with “enough”? What would a United States whose people have enough look like? It would not be one in which tiny numbers of the staggeringly wealthy made hundreds of billions more dollars and the country’s military-industrial complex thrived in a pandemic, while so many others went down in disaster.

This empire will fall sooner or later. They all do. So, this crisis, just at the start of the Biden and Harris years, is a fine time to begin thinking about what might be built in its place. What would any of us like to see from our front windows next year?

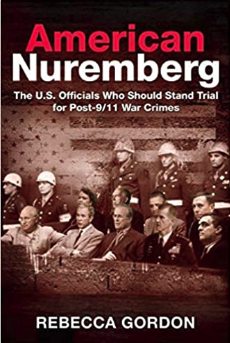

Copyright 2021 Rebecca Gordon

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel Frostlands (the second in the Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Via Tomdispatch.com

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved