Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Today is ten years since Egyptian youth gathered in Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo demanding the resignation of Egypt’s brutal and corrupt Interior Minister, Habib Adly. Even those who called for the rally were surprised by the thousands of youth and workers that showed up, on Egypt’s Police Day, and by their determination to camp out in the square until not only Adly was gone was also the president for life, former Air Force general Hosni Mubarak.

The determination of the youth and other disadvantaged groups provoked the Egyptian officer corps to put Mubarak on a helicopter in mid-February, making a coup and appointing a provisional government.

The U.S. and Egypt are very different places, but perhaps Americans can sympathize better with what Egypt has been through if we consider some similarities related to political movements. Egypt suffered from some of the same deep social problems as the United States.

1. The party representing the wealthy and their lower middle class clients insisted that it could never lose an election. This has become true of a substantial section of the Republican Party in the U.S., and was true of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party in Egypt. When parties become inflexible and refuse to share power, they set up the conditions for a revolution.

2. Wealth inequality cut like a sabre through the social cohesion of the society. In the United States, the top 1% owns nearly 40% of the privately held wealth. Back in the Eisenhower era in the 1950s, the top 1% owned 25% of the privately held wealth. But in today’s US, the top 0.1% own as much as 20% of the privately held wealth, as much, likely as 85% of the US population. Gilbert Achcar writes, “Egypt’s EHII Gini coefficient increased from 42.7 in 1970, the last year of Nasserite ‘socialism’, to 53.7 in 2015.” A Gini coefficient measures inequality, with 1 as perfectly equal and 100 completely unequal.

3. Youth unemployment in the U.S. has risen to over 12%. Youth unemployment in pre-revolutionary Egypt was nearly a third.

4. Mubarak’s Egypt was highly corrupt. People not in the magic circle of the Mubaraks had no hope of sharing in the bonanza. Egypt ranks 106 out of 180 countries for corruption. Although the U.S. is supposedly 23, those rankings aren’t taking into account what the Trumps did to the U.S., with the importation of the swamp of New York real estate practice into Washington, D.C.

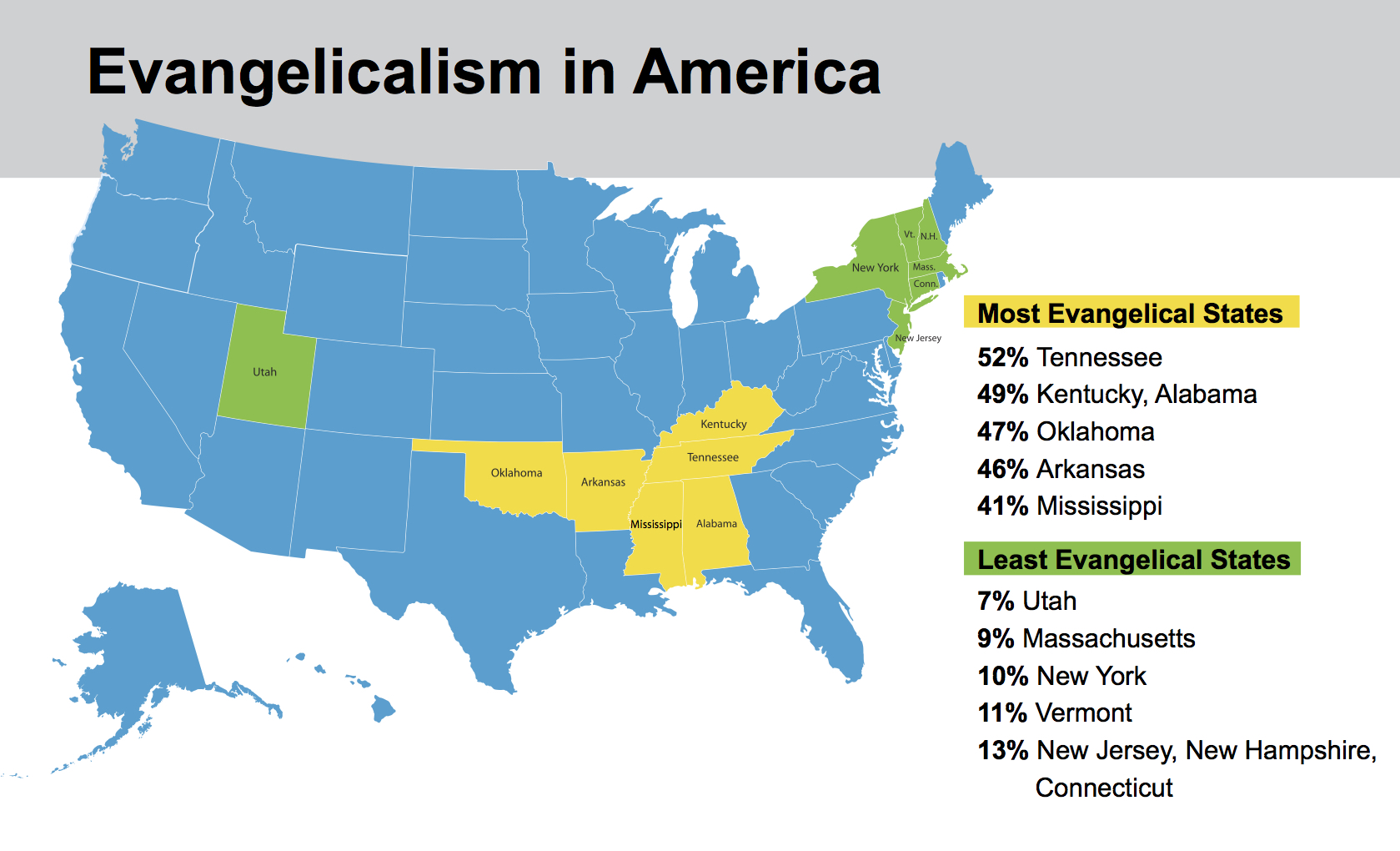

5. There is a severe rural-urban divide in Egypt. Most of the votes for the Brotherhood came from rural areas. Cairo and Alexandria, the big cities, rejected the Brotherhood constitution. This divide destabilized Egypt.

In the US, as well, urban and rural people are at daggers drawn. Most people in cities are Democrats. The red states are more rural, and while evangelicals are found in many social settings, they predominate in states that are less urban.

In revolutionary Egypt 2011-2014, the military never ceased to hold power behind the scenes, but permitted elections for a parliament to be held in autumn, 2011, which were won by the Muslim Brotherhood and the fundamentalist Salafis.

Many corrupt and very wealthy cronies of Mubarak were tried or were fined by the revolutionary government, angering the upper class, helping create the conditions for a counter-revolution.

Egypt held presidential elections in two rounds, in May and June, 2012. Mohammad Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood leader, won the presidency, to the dismay of most of the urban population and of the officer corps, and of the progressive youth who had spearheaded the revolution. The youth were somewhat more upset, though, by continued military oversight of the government.

I wrote about these events in my book,

The New Arabs: How the Millennial Generation is Changing the Middle East (Simon and Schuster repr. 2015).

Morsi increasingly outraged the activist youth, factory workers, urban women, and even nationalist villagers, and by June, 2013, tens of millions were in the street demanding a recall election.

Field Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who served as Minister of Defense, stepped in to demand that Morsi find an accommodation with massive crowds, which threatened to destabilize the country. When Morsi refused to compromise, al-Sisi had him arrested and made a coup. Since the move had the backing of tens of millions, there was a debate over whether it was a coup or a revolution. I suggested that it had elements of both and was a “revocouption.” In some ways, so was the Young Officer coup of 1952.

Al-Sisi initially paid lip service to the 2011 youth revolution, but his actual intent was to restore dictatorship, and, indeed, to deepen the dictatorship to the point of North Korea style totalitarianism. In August, 2013, he moved against a Muslim Brotherhood square occupation, killing some 600 and brutally clearing it. The Brotherhood, a legitimate political party as recently as June, which held the presidency, was suddenly turned into a “terrorist” organization by military fiat and thousands were imprisoned. Al-Sisi ran for president in phony elections in summer, 2014, from which his potential rivals were excluded by threats or imprisonment, and of course he won overwhelmingly.

The military junta hiding behind the new “president” (who put on a suit) had decided that the 2011 revolution took place because Mubarak had made a big mistake. Mubarak had operated on the theory that in a dictatorship, you can only maintain stability by letting people blow off a little steam. A few dissident columns in the newspaper here, a few blog entries there, a few small demonstrations time to time, would be tolerated.

But then those various ways of blowing off steam suddenly ballooned on January 25 into a full-blown revolution.

So the al-Sisi regime decided that no steam would be blown off. No demonstrations would be allowed (despite the provision in the new constitution). No critical journalism would be allowed. No critical blogs. No political satire. Hell, no real newspapers. Demonstrators, bloggers, journalists would all be given long sentences for crossing the government.

Heroes of the revolution like Alaa Abdel Fattah and Ahmed Maher were jailed for years. Alaa is still in jail.

Giulio Regeni, an Italian graduate student doing a Ph.D. at Cambridge on labor activism, was kidnapped by state security men and tortured to death in 2016 to acquire information about the activists he was studying. Then his body was placed in a vehicle and set on fire in a brain dead attempt to make it look like an accident. Egypt-Italy relations have never recovered.

It is no accident that Trump got along famously with al-Sisi. Both are narcissists and authoritarians.

The U.S. government is not a military dictatorship, though Trump did try to use the military against peaceful protesters at LaFayette Square and sent unidentified federal agents to whisk way 200 people from the streets of Portland, Or.

Al-Sisi is also a science denialist. He claimed that the Egyptian military physicians had cured AIDS, rather as Trump claimed that the novel coronavirus was a mirage that would magically disappear (rather than, as it has, killing 400,000 Americans).

Egypt is often referred to as a stalled society, with the stranglehold of the military preventing a healthy civic and intellectual life and even preventing a healthy economy (the military owns a lot of it).

One worries that the United States is also becoming a stalled society, with our billionaire class imposing their monopolies and opposing a living wage, and now they started calling the press the enemy of the people, just like al-Sisi.

Some of the tut-tutting you might otherwise hear in Washington on this anniversary of a failed revolution will be muted. We’re limping along right now, ourselves.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved