By Traci Morris | –

President Biden’s nomination of U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico to lead the Department of the Interior is historic on many levels. Haaland, an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Laguna, was one of the first Native American women elected to Congress, along with U.S. Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas. And if confirmed, she will be the first Native American to head the agency that administers the nation’s trust responsibility to American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Indian Country has a significant history with the Interior Department that has more often been bad than good. But Haaland’s record shows that she is committed to making progress on larger challenges that affect all Americans. She has been especially vocal on climate, environmental protection, public lands and natural resource management.

As the executive director of one of the only Indigenous policy institutes in the nation, a scholar of Indigenous studies and a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma, I’ve been acutely aware of Haaland’s work since she was elected to Congress in 2018. I’ve tracked her leadership on issues such as broadband access and infrastructure for Native nations.

Bloomberg: “Deb Haaland Will be the First Native American Interior Secretary”

”

Accepting President Biden’s nomination as secretary of the interior, U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland observed, “This moment is profound when we consider the fact that a former secretary of the interior once proclaimed his goal to ‘civilize or exterminate’” Native Americans.”

To Indian Country, Haaland is viewed as everybody’s “auntie.” Having her in leadership gives Native America a seat at the policymaking table. For New Mexico she has been a productive member of Congress, reelected in 2020 with over 58% of the vote. And while a few Western senators have called her views “radical,” I believe that Native issues are American issues. If Haaland is confirmed as interior secretary, many observers expect her to provide bold leadership for an agency that oversees what is arguably the heart of America: its land.

A big portfolio

Haaland grew up in a military family, raised a daughter as a single parent and worked in tribal administration before entering politics. A self-described “proud progressive,” she supports policies including a ban on hydraulic fracking, the Green New Deal, a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and a national single-payer health care system.

Haaland’s knowledge of Native and Western issues are important credentials for heading the Interior Department. Created in 1849, the agency manages U.S. cultural and natural resources. It has nine technical bureaus, eight offices and 70,000 employees, including many scientists and natural resource management experts.

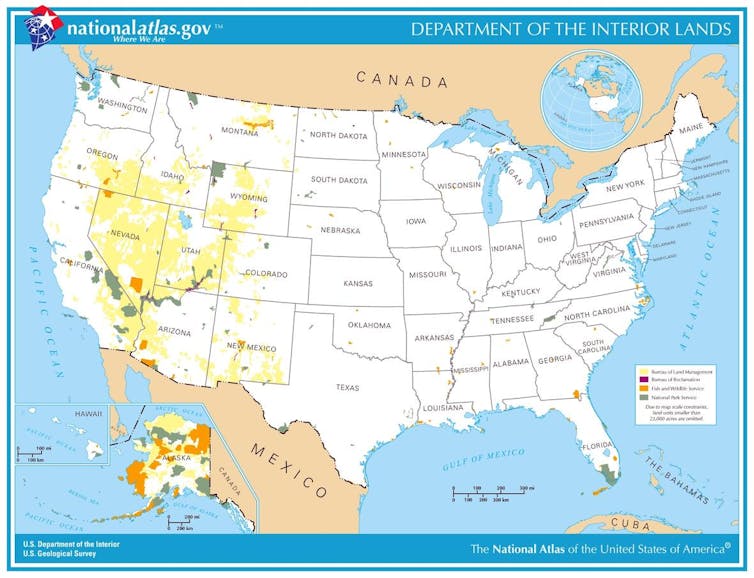

The department’s portfolio includes national parks and wildlife refuges, multiuse public lands, ocean energy development, regulation of surface mining and mine cleanups and research conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey. It oversees the use of more than 480 million acres of public lands, mainly in Western states, 700 million acres of subsurface minerals and 1.7 billion acres of the outer continental shelf along U.S. coastlines.

USGS

One key departmental mission is fulfilling the trust responsibility – a legal obligation that the U.S. has to uphold promises made to tribal nations in exchange for their lands. This political relationship is derived from 370 treaties between the federal government and Native nations.

Tribal nations are part of the family of governments in the U.S., along with the federal and state governments. There are 574 federally recognized sovereign tribal nations that have a nation-to-nation relationship with the U.S. government via the trust relationship. They are located in 35 states on 334 reservations. Tribal lands total 100 million acres.

According to the National Congress of American Indians, the trust responsibility covers two significant interrelated areas:

– Protecting tribal property and assets that the U.S. government holds in trust for the benefit of tribal nations.

– Guaranteeing tribal lands and resources as a base for distinct tribal cultures, including water for irrigation, access to fish and game and income from natural resource development.

The term “Indian Country” is a legal designation of tribal lands. It is also a philosophical definition of where we as Indigenous people are from.

Native nations and the Interior Department

Indian Country and the Interior Department have had a history fraught with controversy that makes this nomination particularly powerful.

One of the most significant issues has been the agency’s long-standing mismanagement of Indian lands on behalf of hundreds of thousands of individual Native Americans since the late 1880s. In 2009, the Obama administration negotiated a US$3.4 billion settlement in a long-running class-action lawsuit against the Interior Department. Elise Cobell, a member of the Blackfeet Nation, brought the suit on behalf of more than 250,000 plaintiffs.

A current issue is the struggle over Oak Flat, a sacred Apache location in southern Arizona that is about to be mined for copper. The site is both culturally and archaeologically significant. Several different groups are suing to prevent mining there, and members of Congress have introduced legislation to block the federal government from transferring title to the land to mining companies.

Another example is the struggle over the Dakota Access Pipeline, which members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and other water protectors argue threatens Native burial sites and water supplies. Still another controversy is the Trump administration’s decision to shrink the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which protects sites that are sacred to more than 20 tribes and pueblos. President Biden is reviewing the Bears Ears decision, and tribes and environmental advocates are urging him to shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Beyond these high-profile cases, Interior Department actions affect many other facets of tribal governance. For example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs oversees tribal gaming compacts and right-of-way infrastructure decisions for projects that cross Native lands.

Many of the agency’s resource stewardship activities also affect tribes. The department recently approved a drought contingency plan for the Colorado River that will impose water conservation requirements on multiple states, counties and tribes. And resource development proposals often affect lands that are important to Native Americans even if they are not officially part of a reservation, but are traditional homelands or sacred spaces.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Since the trust relationship includes a relationship between governments, all federal agencies must fulfill it. President Biden issued a Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening the Nation-to-Nation Relationships on Jan. 26. This policy statement, which builds on and expands similar declarations from Presidents Clinton and Obama, has been well received in Indian Country.

If Haaland is confirmed, Biden’s memo will require her to submit a detailed implementation plan and progress reports to the Office of Management and Budget. Tribal consultations are already planned. Policy experts expect that overall, Haaland will work to restore tribal lands, address climate change – which is significantly affecting Indigenous people – and safeguard natural and cultural resources. The Biden-Harris Plan for Tribal Nations outlines this agenda.

Indigenous issues are American issues

I believe that as secretary of the interior, Haaland will focus on issues that are important to all Americans, not just Indigenous people. Recent surveys show that a majority of Americans think the federal government should do more to combat climate change and protect the environment. “I’ll be fierce for all of us, for our planet, and all of our protected land,” Haaland said when her nomination was announced.

For Native Americans, seeing people who look like us and are from where we come from in some of the highest elected and appointed offices in the U.S. demonstrates inclusion. Indian Country finally has a seat at the table. The gravity of this position is not lost on Haaland, and I expect that she will make a difference for all Americans.

Traci Morris, PhD, Executive Director, American Indian Policy Institute, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved