By Christopher Hedemann, Eduardo Gresse, and Jan Petzold | –

( The Conversation ) – If you read the scientific literature, there seem to be countless pathways and scenarios that might lead us to global deep decarbonisation by 2050, allowing us to meet the 1.5°C target. “It’s still possible,” is the message, “if only we have the political will”.

But what is the extent of our political will, and more importantly, what are the deeper social dynamics driving it? Is it not only possible, but in fact plausible that we will reach deep decarbonisation by 2050 and meet the associated 1.5°C target? These are some of the questions that we asked ourselves in the recent inaugural Hamburg Climate Futures Outlook, a report compiled by more than 40 academics from across various disciplines including sociology, macroeconomics and the natural sciences.

We took a new approach to the study of climate futures, one that goes beyond previous efforts by the IPCC, the International Energy Agency and others, which assessed futures that are merely possible or feasible. “Possible” simply describes an accordance with natural laws, while “feasible” means that there are no or few barriers to a particular future. For example, it is technologically and economically feasible (and clearly possible) that you sell your car and buy a bike. Bikes are a mature technology and cheaper to maintain than cars. But will you? It’s also feasible that 20% of the UK becomes vegetarian by next year. But will they?

Plausible, on the other hand, means that something has more than an outside chance of occurring – it has an appreciable probability. In the context of climate futures, this means that a scenario is not merely feasible, but also that there is enough societal momentum and political will to make that future materialise.

There is no hard, quantitative limit for “appreciable” probability or “enough” political will. But our assessment didn’t need to split hairs in this way. The evidence was overwhelming.

Assessing both social and physical plausibility

In our study, we first formed a picture from existing research of what is needed for deep decarbonisation by 2050. Negative emissions technologies like BECCS – burning biofuels for energy and capturing the resulting CO₂ – can help. But these technologies can’t be the whole solution, because there are feasibility barriers to deploying them at scale.

Deep decarbonisation requires that we reduce anthropogenic emissions in the first place. In fact, we need a year-on-year reduction in emissions from now until 2050, roughly equivalent to the 7% reductions seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since zero-carbon technologies can take decades to scale up and optimise, and lock-in effects commit us to the technologies we choose now for years to come, we also need to act fast.

To study the social dynamics needed for such a rapid transformation, we looked at ten social drivers of decarbonisation: United Nations climate governance, transnational initiatives, climate-related regulation, climate protests and social movements, climate litigation, corporate responses, fossil fuel divestment, consumption patterns, journalism, and knowledge production. We studied the drivers’ current trajectories, but also the enabling or constraining conditions that influence their future development.

We found, for example, that consumption will keep growing due to a lack of regulation and strong cultural habits of consumption, “green” or otherwise. While the way in which we consume changed rapidly during the pandemic, shifting online, what and how much we consume is anchored in cultural habits and attitudes.

We found that divestment – selling investments in fossil-fuel infrastructure – is occurring to some extent, but with unexpected negative spillover effects, such as when nation states divest at home but reinvest in fossil fuels abroad. And we found that social movements have a positive effect in some countries, but it remains uncertain how their political vision will mature after the pandemic, or in key countries like China, where protests do not usually have an influence on national politics.

None of the drivers show enough momentum to bring about deep decarbonisation by 2050, and two drivers, consumption patterns and corporate responses, actively inhibit it. Our final assessment: even if a partial decarbonisation is currently plausible, deep decarbonisation by the year 2050 is not.

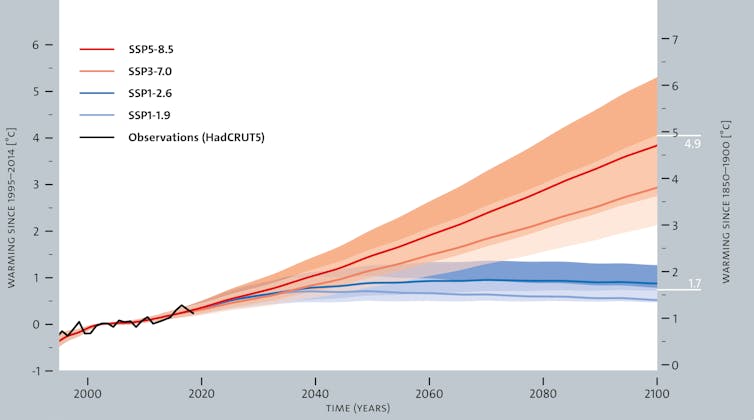

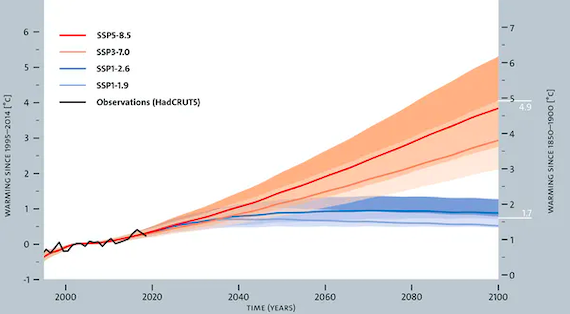

We then combined our assessment of social plausibility with the latest set of socioeconomic future emissions scenarios and the latest physical science research on climate sensitivity – how much the climate will warm after a given amount of CO₂ emissions. This joint physical and social assessment evaluates warming lower than 1.7°C and warming higher than 4.9°C by the end of the century as currently not plausible.

Hamburg Climate Futures Outlook

Game over?

So, is this scientific proof that we should give up on the 1.5°C target? Absolutely not. We assessed the current state of evidence from the physical and social worlds, but the future is open. That’s why our climate futures outlook is designed to be an annual publication.

Deep decarbonisation could become more plausible, but this future would also require a good deal of tenacity. Rapid cuts in emissions may take a long time to show up in atmospheric CO₂ concentrations and warming trends – perhaps decades. Not only will we need to implement radical changes, we will also need to remain committed to seeing those changes through, beyond the time frame of one election cycle.

Though the 1.5°C target might be possible, there are currently no grounds for optimism that we will meet it. But perhaps our findings will provide exactly the motivation we need to make it happen.

Christopher Hedemann, Postdoctoral Scientist in Climate Futures, University of Hamburg; Eduardo Gresse, Postdoctoral Scientist in Climate Futures, University of Hamburg, and Jan Petzold, Postdoctoral Scientist in Climate Futures, University of Hamburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved