By Maya Abuali | –

( Middle East Monitor) – Lacking in 60 per cent of appropriate medicine and treatment protocols as a result of the siege, Gaza’s already deficient cancer care is slipping further into chaos as restrictions grow harsher.

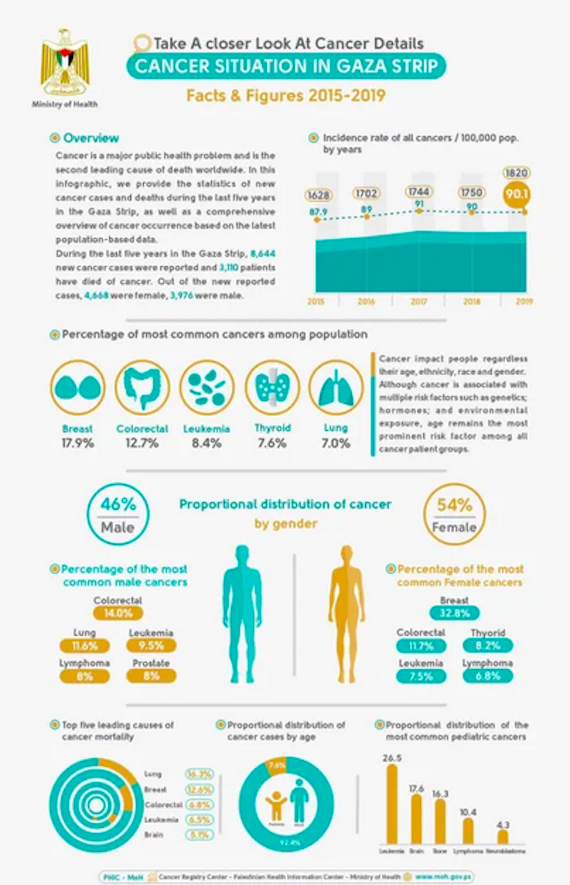

Beyond dealing with the Gaza Strip’s already uninhabitable living conditions, Palestinian cancer patients in the enclave are unable to receive proper treatment due to numerous obstacles imposed by the Israeli occupation state. With a population of two million in only approximately 365 square kilometres of land, the Gaza Strip has seen around 1,800 new cancer cases each year, while lacking 60 per cent of the appropriate medicine and treatment protocols. Patients living in Gaza are therefore forced to seek treatment in hospitals in the occupied West Bank and Jerusalem or within Israel. However, due to the restrictions placed on their movement by the Israeli occupation, they often fail to do so in time.

Shortages in adequate care

Data provided to Middle East Monitor by the Al-Rantissi Specialised Hospital in Gaza indicates a major absence of sufficient tools to allow for standard and safe multidisciplinary cancer care. This includes a shortage of trained staff, medical equipment and adequate protocol such as screening for colorectal cancer. There is no main cancer services centre in Gaza, and capacity in cancer facilities such as the Al-Rantissi hospital have been exceeded and are projected to continue to do so in the coming years. Due to the restrictions imposed on imports by the occupation’s siege of the enclave, there is a significant lack in new medicine for breast and colon cancer and chemotherapy, as well as no radiation therapy machines at all. There is also a pressing want for cancer specialists and training programmes for cancer doctors and nurses in the region. These shortages have resulted in severe ramifications; for instance, breast cancer patients — which constitute 15 per cent of all cancer patients in Palestine — have a five-year survival rate of 40 per cent in Gaza, compared to other countries, where the rate stands at approximately 90 per cent.

Dr. Zeena Salman, a pediatric oncologist who has treated children with cancer at Al-Rantissi, explained the dire nature of these issues. “The [challenging] thing in Gaza is because all access [to medicine] is controlled through two checkpoints […] there’s frequent shortages in terms of chemotherapy, there’s no access to radiation therapy, there’s [often] no access to different surgical sub-specialists…,” Salman says in an interview with Middle East Monitor. “You have a strict treatment protocol in Gaza — all of our treatment protocols are very strict in terms of dosing, type of medication, the timing […] things have to happen in such a tight period of time and it’s such a complex process that requires so many different disciplines of medicine.”

Dr. Salman is currently working on several projects including building a cancer registry for children across Palestine so that doctors are able to track every single child struggling with cancer to record their outcomes, place of treatment, specific medicinal needs/shortages, and how they can improve their survival rates.

Dr. Zeena Salman, a pediatric oncologist

The pediatric adds: “We know for adults that screening leads to earlier detection, it makes cancer more manageable, easier to treat, so certainly having good screening programs in place is a huge asset to being able to care for cancer patients and makes their cancer more treatable as they’re detected earlier.”

“Also, when you have access to care that doesn’t require crossing checkpoints, having access to [treatment] that’s available locally, having that multidisciplinary care locally, increases cure rates significantly… and the lack of that we know impacts mortality significantly.”

The detrimental impact of the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has only crippled matters further, with cancer sections in hospitals forced to close to accommodate more beds for patients suffering from the virus. There has also been a serious diversion of already scanty resources.

“When resources have to be diverted for patients in respiratory distress because of COVID-19, that leaves no access to ICU beds, or emergency rooms,” Salman explains. “[It has caused] those resources [to be channeled] away from patients with chronic diseases like cancer. There has been a huge impact on both morbidity and mortality for cancer patients, adults and children.”

To add to the challenges doctors and patients face in Gaza, three months ago, Israel launched a new bombing campaign against Gaza, killing at least 254 Palestinians including 66 children and two senior doctors in the space of 11 days. It also caused significant damage to the Palestinian Ministry of Health and Gaza’s only COVID-19 lab and other medical facilities, forcing patients to be moved to other treatment centres which were already at full capacity. Dr. Ayman Abu Alouf, head of Gaza’s coronavirus response operation, was killed in an Israeli attack on his home.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) stated that nearly 30 hospitals and health clinics in the Strip were either flattened or significantly damaged by the Israeli air strikes. Approximately 46 per cent of essential drugs and 33 per cent of essential medicines were rendered unusable.

With the already meagre resources for cancer treatment in Gaza being rerouted due to the pandemic and depleted further by tightening restrictions on import, more patients have been forced to seek treatment outside of the enclave. According to Dr. Muhammad Abu Nada, head of the Al-Rantissi Oncology Department, between 50-60 per cent of cancer patients in Gaza require urgent treatment outside of Gaza, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy and atomic scanning, which are not available in the Strip. Although the occupation state opened the Erez-Beit Hanoun crossing on 3 June, individuals are forced to go through a complex and lengthy referral and permit system to obtain approval to leave Gaza. The referral may be issued within weeks, or in many cases they are rejected by the Israeli authorities, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health.

“They have to obtain a medical referral from the doctor, they have to go to the referral’s office after that, then they have to obtain an appointment from an outside hospital that’s willing to accept them for the treatment that’s not available, and they have to apply for a permit from Israel to be able to leave to get to that appointment, they have to have many weeks’ notice for the appointment…,” Dr. Salman explains. “So it can take weeks or longer to go out and leave Gaza if they’re missing some piece of their care, and this leads to huge delays in treatment, if they get the permit they requested. They’re not always approved.”

The permit system creates bureaucratic barriers to timely access to health care for patients. As a result of the Israeli siege imposed on Gaza in 2007, about 60 per cent of patients have been denied access to the specialised hospitals required for their care this year, the ministry says. A report conducted by the WHO entitled ‘Right to Health‘ stated that in 2018 almost 39 per cent of patient permit applications were unsuccessful; they were either denied outright or delayed, with patients receiving no definitive response to their applications by the time of their hospital appointment. Research from the report details that in 2019, cancer patients requiring chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy who were initially denied or delayed permits between 2015 and 2017 were 1.5 times less likely to survive in the years after application compared to patients who were initially approved permits.

“We just know that there are so many barriers to reaching the 80% cure rate [which we see in the United States],” Dr. Salman says. “[…] We can always try and build capacity but because of this very complicated permit and referral system, so many things are out of our hands even as people who want to help build up services available locally.”

Calls for international support

At a press conference held last week, Dr. Abu Nada attributed the barriers faced by cancer patients in Gaza to the blockade. “The retention of the Israeli siege on Gaza, which is the reason for the lack of medicines and putting restrictions on the movement of the patients who need treatment in the West Bank, Jerusalem or Israel, has resulted in the deaths of many cancer patients.”

The conference, which was held by the Ministry of Health at the Al-Rantissi hospital, included the participation of many children with cancer. The purpose of the event was to raise awareness of their ongoing suffering, and to call on all international humanitarian bodies and institutions to support the right to treatment for patients in Gaza and provide them with sufficient medicine and equipment to recover. Dr. Abu Nada also requested the international community pressure Israel to lift the restrictions imposed on travelling for patients from Gaza to allow access to hospitals in the West Bank which can put them on a road to recuperation.

With a third of cancer patients in the Strip minors, the lack of access to the necessary medical care is not only increasing patient agony, it is another tool used by the occupation to destroy the lives and future of Palestinians. As an occupying power, Israel has a legal obligation to ensure Palestinians’ right to health, and that is the least Gaza’s population deserves.

—

Maya Abuali is a Palestinian honours Classics student at McGill University and a Managing Editor at the McGill Tribune in Montreal. Having lived in Hong Kong and Jordan, she speaks English, Arabic, and Mandarin and reads Latin and Ancient Greek. Maya has interned as a writer and editor for Athens Insider magazine and USAID Jordan and currently manages the News and Arts & Entertainment sections for a Montreal-based newspaper.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor or Informed Comment.

This work by Middle East Monitor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved