By Richard Holden | –

World leaders and about 30,000 others from assorted interest groups will converge on Glasgow in November for the United Nations’ 26th annual climate summit, COP26 (“Conference of the Parties”).

It will be five years (allowing for a one-year Tokyo 2020-style pandemic hiatus) since the Paris Agreement adopted at COP21 in 2015.

There has been plenty of cynicism about that agreement, its structure and non-binding nature. Important emitters like China were effectively exempt from making meaningful carbon-reduction commitments.

Some OECD countries (such as Canada) have paid lip service to the agreement but done little. Still others (such as Australia) have made some progress reducing emissions but have no long-term plan, relying instead on bumper-sticker slogans about “technology not taxes” and, until recently, hiding behind dodgy accounting tricks.

That aside, it’s hard to see how the world solves what amounts to — as economists put it — a “coordination problem” without global agreements.

For roughly half a century economists have been unanimous about what those agreements must involve — a price on carbon. The 2018 economics Nobel prize awarded to William Nordhaus was belated recognition of this fact.

A price on carbon — in the form of a carbon tax or emissions trading scheme — is a way to use the power of the market’s price mechanism to balance the good that comes from emitting carbon (economic development) with the bad (climate change).

Set the price of carbon at the true social cost of carbon (taking into account all the ills that come from climate change) and the invisible hand of the market will balance the pros and cons. Think of it as Friedrich von Hayek meets Greta Thunberg.

But there is another, less dramatic way to harness market forces to reduce carbon emissions: disclosure.

Public disclosure works

The idea starts with this: plenty of consumers want to reduce their carbon footprint and are willing to pay for it. That’s why people recycle, use green energy even when it’s more expensive, buy low-carbon clothing, and drive electric cars. A bunch of folks are willing to pay to be green.

The success of companies such as eco-friendly sneaker company Allbirds and electic vehicle maker Tesla exist is evidence of the market catering to these consumer preferences. But can we make it easier for consumers to express their environmental preferences? Can we turbocharge the market for greener products?

A working paper published this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests the answer is “yes”.

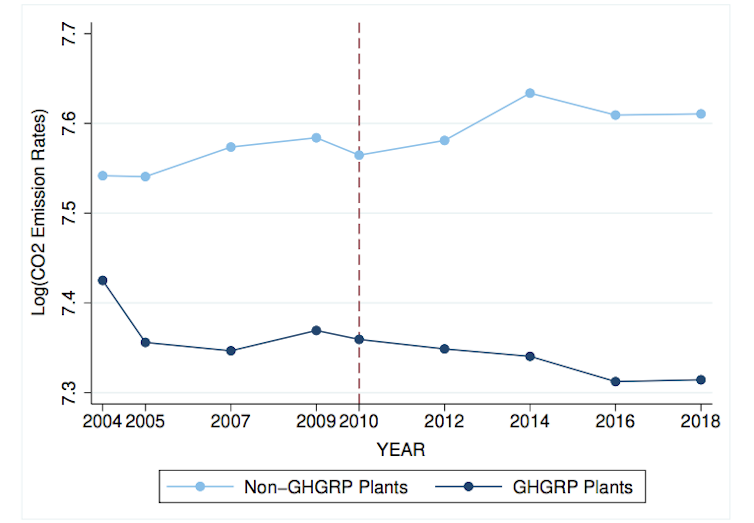

Authored by Carnegie Mellon University economists Lavender Yang, Nicholas Muller and Pierre Jinghong Liang, the paper looks at the US Environmental Protectino Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program. In effect from 2010, this has required big carbon emitters (including all power plants that produce more than 25,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year) to publicly disclose how much they emit.

The authors look at the effect of this disclosure program on the electric power industry, which accounts for 27% of all US emissions.

The results are striking. Plants subject to greater scrutiny reduced their carbon emissions by 7%. Plants owned by publicly listed companies reduced their emissions by 10%. Large public companies, such as those in the S&P500 stock index, cut emissions even more (11%).

Accountability increases environmental performance

NBER Working Paper 28984

Responding to investor concerns

The reason appears to be responsiveness to investors wanting companies to be more environmentally responsible. This explains why emissions went down more for public companies, and even more for large public companies, whose shares are more likely to be held by funds with an ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) mandate.

Some of these investors have pro-social preferences and want to invest their money in more sustainable companies. Others might not care about the environment per se, but know that lots of folks do. Businesses that cater to these consumer preferences have an advantage.

The dark side to this is that the decline in emissions by major plants was partially offset by an increase in emissions by plants under the 25,000-tonne threshold not subject to disclosure.

In other words, companies responded to the incentives provided by disclosure requirements. Those who could “hide” their emissions did not.

The lesson is that disclosure requirements work. They force companies to own up to their customers and investors, and face the reality of their emissions behaviour. But we need to apply it to all companies, not just big ones.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

——-

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved