By Mojtaba Sadegh, John Abatzoglou and Mohammad Reza Alizadeh | –

The Western U.S. is experiencing another severe fire season, and a recent study shows that even high mountain areas once considered too wet to burn are at increasing risk as the climate warms.

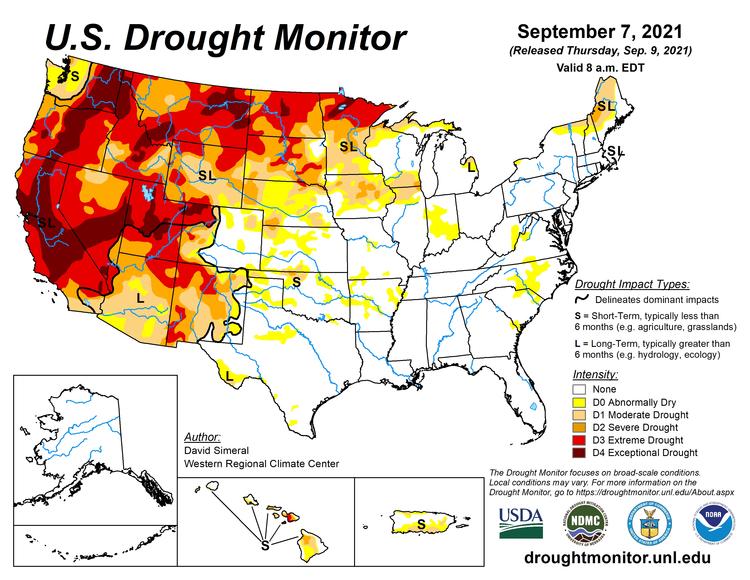

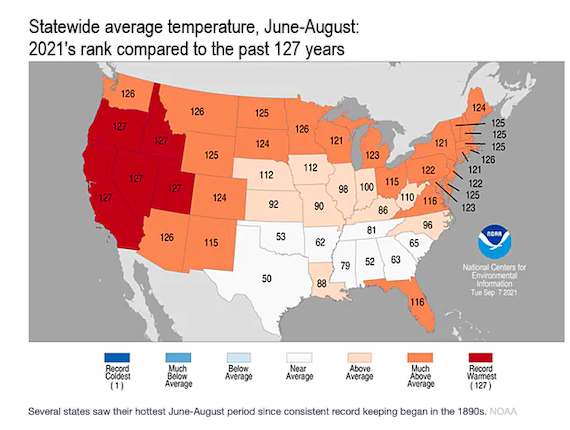

With more than 5 million acres already burned by early September, the 2021 U.S. fire season is about on pace with the extreme fire season of 2020. This summer has been the hottest on record and one of the driest in the region, with 80% of the Western U.S. in severe to exceptional drought. That combination of heat and dryness is a recipe for disastrous wildfires.

In a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences released in May 2021, our team of fire and climate scientists and engineers found that forest fires are now reaching higher, normally wetter elevations. And they are burning there at rates unprecedented in recent fire history. Two fires burning in northern California in 2021 – the Dixie and Caldor fires – are examples: They were the first and second wildfires on record to cross the Sierra Nevada crest and burn on both sides.

While historical fire suppression and other forest management practices play a role in the West’s worsening fire problem, the high-elevation forests we studied have had little human intervention. The results provide a clear indication that climate change is enabling these normally wet forests to burn.

As wildfires creep higher up mountains, another tenth of the West’s forest area is now at risk, our study found. That creates new hazards for mountain communities, with impacts on downstream water supplies and the plants and wildlife that call these forests home.

Rising fire risk in the high mountains

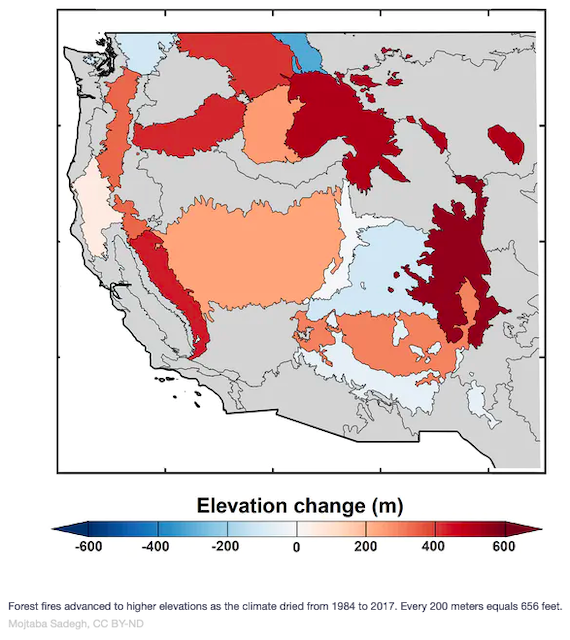

In the new study, we analyzed records of all fires larger than 1,000 acres (405 hectares) in the mountainous regions of the contiguous Western U.S. between 1984 and 2017.

The amount of land that burned increased across all elevations during that period, but the largest increase occurred above 8,200 feet (2,500 meters). To put that elevation into perspective, Denver – the mile-high city – sits at 5,280 feet, and Aspen, Colorado, is at 8,000 feet. These high-elevation areas are largely remote mountains and forests with some small communities and ski areas.

The area burning above 8,200 feet more than tripled in 2001-2017 compared with 1984-2000.

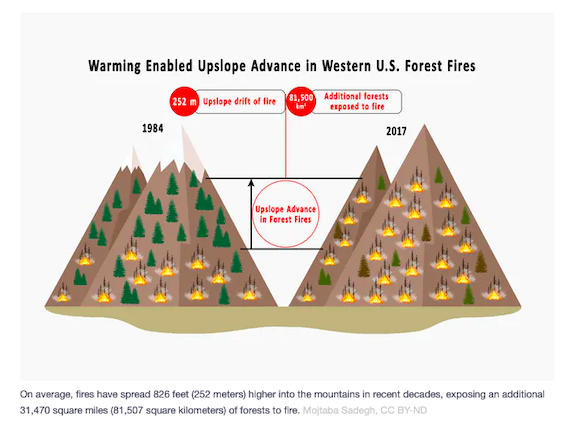

Our results show that climate warming has diminished the high-elevation flammability barrier – the point where forests historically were too wet to burn regularly because the snow normally lingered well into summer and started falling again early in the fall. Fires advanced about 826 feet (252 meters) uphill in the Western mountains over those three decades.

The Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado in 2020 was the largest fire in the state’s history, burning over 208,000 acres (84,175 hectares), and is a prime example of a high-elevation forest fire. The fire burned in forests extending to 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) and reached the upper tree line of the Rocky Mountains.

We found that rising temperatures in the past 34 years have helped to extend the fire territory in the West to an additional 31,470 square miles (81,507 square kilometers) of high-elevation forests. That means a staggering 11% of all Western U.S. forests – an area similar in size to South Carolina – are susceptible to fire now that weren’t three decades ago.

Can’t blame fire suppression here

In lower-elevation forests, several factors contribute to fire activity, including the presence of more people in wildland areas and a history of fire suppression.

In the early 1900s, Congress commissioned the U.S. Forest Service to manage forest fires, which resulted in a focus on suppressing fires – a policy that continued through the 1970s. This caused flammable underbrush that would normally be cleared out by occasional natural blazes to accumulate. The increase in biomass in many lower elevation forests across the West has been associated with increases in high-severity fires and megafires. At the same time, climate warming has dried out forests in the Western U.S., making them more prone to large fires.

By focusing on high-elevation fires in areas with little history of fire suppression, we can more clearly see the influence of climate change.

Most high-elevation forests haven’t been subjected to much fire suppression, logging or other human activities, and because trees at these high elevations are in wetter forests, they historically have long return intervals between fires, typically a century or more. Yet they experienced the highest rate of increase in fire activity in the past 34 years. We found that the increase is strongly correlated with the observed warming.

High mountain fires create new problems

High-elevation fires have implications for natural and human systems.

High mountains are natural water towers that normally provide a sustained source of water to millions of people during dry summer months in the Western U.S. The scars that wildfires leave behind – known as burn scars – affect how much snow can accumulate at high elevations. This can influence the timing, quality and quantity of water that reaches reservoirs and rivers downstream.

High-elevation fires also remove standing trees that act as anchor points that normally stabilize the snowpack, raising the risk of avalanches.

The loss of tree canopy also exposes mountain streams to the Sun, increasing water temperatures in the cold headwater streams. Increasing stream temperatures can harm fish and the larger wildlife and predators that rely on them.

Climate change is increasing fire risk in many regions across the globe, and studies show that this trend will continue as the planet warms. The increase in fires in the high mountains is another warning to the U.S. West and elsewhere of the risks ahead as the climate changes.

This is an update to a story published May 24, 2021.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Mojtaba Sadegh, Assistant Professor of Civil Engineering, Boise State University; John Abatzoglou, Associate Professor of Engineering, University of California, Merced, and Mohammad Reza Alizadeh, Ph.D. Student in Engineering, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved