Southwest Harbor, Maine (Special to Informed Comment) – Who is at fault for a standoff on the debt ceiling? Republicans are the obvious choice because when in power deficits don’t matter but out of power deficits and a growing debt are the path to hell. Deficits will burden our grandchildren and so we must accept harsh measures. Democrats see this as a route to disaster capitalism. Here is the Economic Policy Institute’s budget balancing scenario: “Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts a budget deficit of just under 12% of GDP for 2021. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) indicates much of this was front-loaded—federal government borrowing averaged 16% of GDP for the first six months of the year. For the rest of the year, assume borrowing averaged about 8% of GDP. This is the gap between tax revenues and spending, so if no more borrowing is allowed due to the debt ceiling, it is de facto a measure of how much spending would have to be cut. A spending cut of 8% of GDP is a mammoth shock, and to have it slam into the economy in an instant would be spectacularly damaging.

But if austerity is a disaster that does not mean that continual rounds of stimulus spending can address either traditional concerns about jobs and social justice or the current and equally pressing dangers concerning climate and biodiversity. Federal dollars are better than austerity but leave gaping holes even as they increase expectations. And as Biden’s election was premised in part on the promise to get things done, the sluggish recovery is charged to him, further reducing his political leverage. And the problem with solely blaming austerity is that its defenders can and will always say you leftists did not cut enough.

Best that we find a diagnosis that touches everyday frustrations mor than abstract fiscal balances. Sonali Kolkatar comments on the high rates of resignation plaguing US workplaces:

- “If such a high rate of resignations were occurring at a time when jobs were plentiful, it might be seen as a sign of a booming economy where workers have their pick of offers. But the same labor report showed that job openings have also declined, suggesting that something else is going on. A new Harris Poll of people with employment found that more than half of workers want to leave their jobs. Many cite uncaring employers and a lack of scheduling flexibility as reasons for wanting to quit…

So serious is the labor market upheaval that Jack Kelly, senior contributor to Forbes.com, a pro-corporate news outlet, has defined the trend as, “a sort of workers’ revolution and uprising against bad bosses and tone-deaf companies that refuse to pay well and take advantage of their staff.” In what might be a reference to viral videos like those of McGrath, Ragland, and the growing trend of #QuitMyJob posts, Kelly goes on to say, “The quitters are making a powerful, positive and self-affirming statement saying that they won’t take the abusive behavior any longer.”

That workplace, such as it is, is sustained by deficits, but not the deficits so frequently lamented. Rather the debt at fault is consumer debt, especially student and mortgage debt.

James Galbraith argues at the Intercept, correctly in my view, that these are structural problems at the heart of much discontent. Workers who abandon the workplace are not lazy beneficiaries of expanded unemployment compensation. They did not rush back to the labor market when those benefits were eliminated. These workers recognize something academic economists often forget—there is a cost to holding a job just as there is to losing one. Especially in a society lacking public transit, travels to and from the job may require a second family car . Add in clothing and increased day care costs and the job becomes a problematic proposition.

Beyond these practical concerns there may be a broader cultural shift. How are these workplace escapees getting along without income or state support. Perhaps many workers have distinguished more clearly between needs and luxuries and/or extended family support, which may not face so much stigma. Or forms of collaboration outside the market may be easing some burdens. In any case it seems likely that workers are much less willing to accept the tyranny of the modern workplace.

We have not heard such talk since the late sixties blue collar blues. Those frustrations were channeled into wage concessions, but workplaces remained contested terrain with deleterious effects on the final product. White working class males made some monetary gains but often at the price of further give backs of workplace autonomy and cost of living clauses that fostered self-reinforcing inflationary spirals.

One constructive response that Galbraith advocates is modest subsidies for small scale local cooperatives, a policy already adopted in Germany. Such enterprises create incentives to identify with the business and thus require fewer supervisory personnel.

Combatting the dangers of austerity may require more than economic arguments. It will also need an ethical critique, one that awards consumption its place. Such a message may seem dangerous in an era of environmental limits. Consumption, however, need not be limited to the corporate driven consumerism of our era. We might revisit John Kenneth Galbraith’s moral critique of two generations ago, with his contrast of private affluence and public squalor. Especially necessary is public sector spending on a new green infrastructure, on preventive health care, university education. Equally important would be public and private art. The gains from technological progress can also be “spent” on more leisure, with all its possibilities, rather than more goods. Austerity is a passionate opponent and demands a multifaceted response.

——

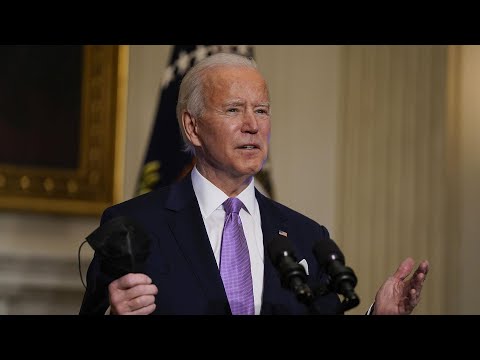

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

Biden Delivers Remarks on his Build Back Better Agenda | NBC News

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved