By Isabel Sutton | –

( Clean Energy Wire) – A string of landmark rulings forcing governments to step up emission cuts have turned the courts into a new and powerful line of defence in the fight against climate change. An increasing number of judges now consider global warming a human rights issue, and therefore refuse to leave climate policy to politicians alone. This shift has spawned a whole new wave of lawsuits across the globe, as climate litigation is no longer considered a symbolic act with slim chances of success. But critics warn that courts may be overstepping their remit, and that climate litigation is a slow and costly process with inherently limited effects.

Judges around the world are pushing the boundaries of their powers to force governments to take more ambitious action against climate change. In a number of recent landmark rulings, they have argued that climate change can no longer be left to politics alone because it is a question of human rights, ushering in a new era in climate litigation.

The verdicts have handed environmentalists a new and highly effective tool, after pressure on politicians and the public failed to result in policies sufficient to limit the rise in global temperatures to the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement.

“The fact that courts are intervening is because climate change is threatening the very foundations of our society,” said Dennis Van Berkel, legal counsel to Urgenda, an NGO that forced the Dutch government to make more drastic emissions cuts in the world’s most famous climate litigation case.

“Courts are saying, listen, there are debates that belong in the realm of politics but there are also fundamental principles behind our constitutions that need to be protected, otherwise the stability of society is at stake,” he told Clean Energy Wire.

Environmental and climate court cases are not new, but they have become more successful than ever before. In recent years, courts have stopped logging in the Polish national park Bialowieza, put an end to clearance of Germany’s Hambach Forest, and enforced driving bans in some of the country’s inner cities. A surprise ruling by Germany’s constitutional court earlier this year showcased the potential effect of carrying the fight against climate change into the courts: Within a week, a befuddled government had sharply increased its climate ambitions. Incited by this success, German activists have now launched a coordinated legal attack to compel carmakers into a faster transition to emission-free cars.

“Anyone who delays climate protection harms others and violates the law,” environmental lawyer Roda Verheyen, who is involved in this lawsuit, told German weekly Die Zeit.

A German court stopped the controversial clearing of the Hambach Forest to make space for a coal mine. Photo by hambacherforst.org

Court rulings have turned climate change into a human rights issue

Climate litigation has become a hot topic largely thanks to a slew of historic decisions that have ordered governments and, in a few cases, companies (notably Shell) to increase their climate ambitions on the basis that they are breaching citizens’ human rights. The gap between scientific understanding of climate change and state failures to mitigate against temperature rises have created a void that courts are increasingly willing to fill.

But litigation is a controversial tool in the fight against climate change. Some argue that courts are acting at the limits of their powers to ensure humanity’s survival and that litigation offers a means of holding governments and companies to account for failing to act over climate change. Others worry that courts are going too far, ruling in ways that threaten the balance of powers on which democratic societies rely, and that litigation is a slow and costly mechanism for achieving results that will always be limited to the jurisdictions in which the cases are heard.

For those who work in the field, the continued inadequacy of politics in the face of ever more urgent scientific reports leaves courts with no choice. Speaking to Clean Energy Wire, Dutch lawyer Professor Dr Jaap Spier, who has authored dozens of books and articles on legal aspects of climate change, said that “while there are difficulties with using the law to offer solutions, if you ultimately take the view this is a matter for politicians, then that means that, for practical purposes, there is no solution and catastrophe has to set in.”

While rights-based and other forms of climate litigation are set to increase, litigation in the opposite direction is also on the rise. In the Netherlands, the success of Urgenda in using the courts to force the government to accelerate its emissions reductions has been followed by the victory of German energy giant RWE, one of Europe’s biggest polluters, claiming 1.4 billion euro in lost profits from the Netherlands’ withdrawal from coal. A similar case is being brought by Uniper and many more such claims are expected over the coming years. Meanwhile, in the US, President Joe Biden’s efforts to reverse the Trump administration’s climate denialism (such as the revocation of Trump’s permit for the Keystone XL pipeline) have been met by multiple legal actions from states and companies.

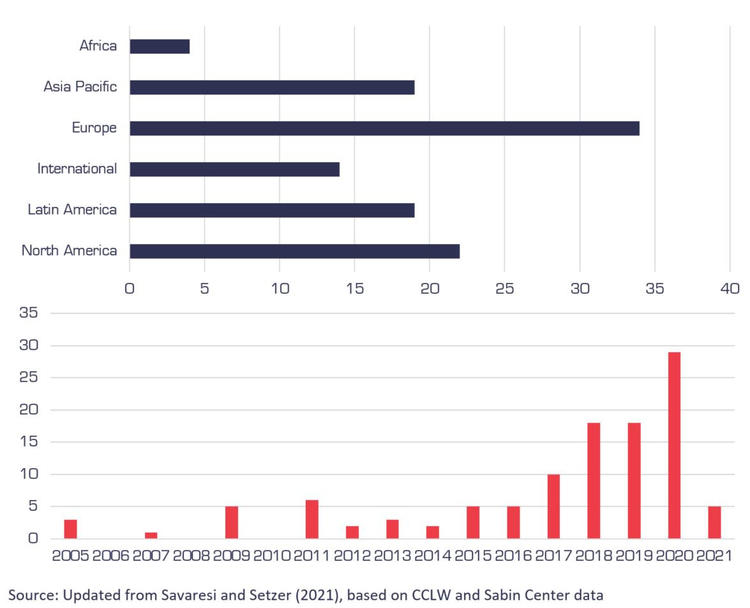

Geographical and chronological distribution of rights-based climate cases (% of cases, to May 2021). Credit: Setzer and Higham, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (2021) based on Climate Change Laws of the World and Sabin Center data

Judges refuse to leave climate change to policymakers

The recent court rulings in favour of more emissions cuts have been hailed as historic victories in the fight against climate change. But they are also profoundly significant in a legal sense, because the inaction of states is compelling judges round the world to push the limits of their powers in extraordinary ways. High courts in the Netherlands, Nepal, Germany and France have ordered their governments to step up climate policies or be liable for human rights abuses.

These judgements test the boundaries of what the courts are authorised to do. In democratic societies, courts do not pass legislation or set policy; they apply existing legislation to the cases brought before them. In these cases, however, courts have taken their role further. “Courts are increasingly addressing how much individual states should reduce emissions, which should in principal be a question for politics,” said Urgenda counsel Van Berkel. “Judges are pushed into this position because we are failing to take the necessary actions to avoid (even) the most dire consequences of climate change.”

Court judgements of this kind are on the rise. According to the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics, “between 2015 and May 2020, litigants brought 36 lawsuits against states, as well as three lawsuits and one investigation against corporations, for human rights violations related to climate change. Prior to 2015, only five rights-based climate cases had been filed in the world.”

“Judges do not want to be first; they’re more comfortable being second and even more comfortable being third,” says Michel Gerrard, founder of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Colombia University. “So the fact that the judge issued the Urgenda decision made it more comfortable for other judges even in other jurisdictions to rule in a similar way.”

“You can see when you talk to national judges they’re looking over their shoulders,” says British-French lawyer Philippe Sands. “They don’t want to be the country that’s left behind.”

A Dutch court hears the landmark Urgenda climate case. Image credit: Chantal Bekker / Urgenda

A Dutch court hears the landmark Urgenda climate case. Image credit: Chantal Bekker / Urgenda

Urgenda set the precedent

The two most important triggers for this rise in rights-based climate cases are the Paris Agreement and Urgenda’s final victory against the Dutch government in 2018. Paris created an enforcement gap, whereby states were demanded to set targets for emissions reductions in accordance with the scientific reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), but crucially without any real system of accountability.

The Urgenda decision required the Dutch government to reduce its emission by 25 percent compared to 1990 levels by 2020 on the grounds that existing targets violated human rights. This was unprecedented. The idea that the state had a duty of care to protect its citizens against climate change had never been established in law before Urgenda. What’s more, Urgenda ordered the government to set a particular target and make a policy for getting there. “It was really the first major decision to order the government to take specific action to reduce greenhouse gases, not based on a statute, but using human rights principles”, says Michael Gerrard of the Sabin Center.

More such judgements have followed. The year 2021 brought an unprecedented number of rights-based climate judgements from courts in Europe. “It is quite remarkable that just in the span of a year, you have an Irish, French, Belgian and German court each basically saying to the governments of their countries that what you’re doing is not enough, you need to do more,” said Urgenda counsel Van Berkel. “This is part of a growing recognition within courts that we’re really going in the wrong direction and that it won’t stop with this one court case. There will be another and another.” The most important of these decisions was the judgement of the German constitutional court which ruled that the government must improve its 2019 Climate Protection Act with ‘more urgent and shorter term measures’ or else be in violation of the constitutional rights of living citizens and its responsibility to future generations. The German government reacted immediately to the court’s ruling, revising its climate policies beyond the targets stipulated in the judgement.

Beyond Europe, several courts have also ruled that governments must do more to protect human rights in relation to climate change and, in some cases, made specific requirements. A major decision by the Supreme Court of Nepal in 2018 instructed the government to pass a climate change law to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change in line with its duties to protect its citizens’ human rights. Another influential case, Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan filed in 2015, resulted in the judge constituting a commission to implement the state’s existing but ineffectual policy on climate action. These were both ground-breaking decisions. Similarly, in Australia, a New South Wales Court judged in a case brought by bushfire survivors that the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) needed to do more to reduce emissions. This decision, published in August 2021, was the first judgement in Australia to order a government organisation to take specific action on climate change.

Court’s “judicial activism” a step too far?

Some lawyers, whilst recognising the acute threat of climate change, are concerned by the role courts are now taking in deciding what states should be doing. Legal scholar Alexander Zahar, who specialises in environmental law, calls the Urgenda and Shell cases examples of “judicial activism” because, in both, the judges went beyond what the law actually says in order to find in favour of the plaintiffs. In the Shell case, Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie) drew on the duty of care and human rights case of Urgenda against the Dutch government and extended it to a private company. The Shell case is highly significant because it is one of the first judgements to take the Paris targets as a legal standard of conduct, despite the absence of explicit legislation, according to the Grantham Institute.

Zahar argues that calling states and companies to account for human rights violations is problematic because climate change is a problem to which we all contribute and we are all responsible for perpetuating. “The judgment against Shell is fundamentally unfair to the company,” Zahar told Clean Energy Wire. “It’s a good company trying to do the right thing. If you twist the law or make up law in court to find a solution to the climate problem, then you are no better than a kangaroo court. You are undermining the legal order. This is very dangerous. And it could be counterproductive in self-defeating ways, such as putting off other good companies from taking the ‘good citizen’ initiatives that Shell took,” he said with reference to Shell’s previous emission-cutting efforts.

Even putting aside the legal and constitutional questions, Zahar and others also argue that litigation is a very ineffectual tool in the fight against climate change; it is a bottom-up response to a problem that demands a top-down solution. Climate action requires urgent and dramatic policy changes; litigation is piecemeal and decisions are limited to each case. Even when there is a favourable judgement, there is no guarantee of impact. Urgenda is currently preparing to take the Dutch government back to court because, in their view, the government is not adequately responding to the demands of the judgement. Emissions continue going up.

Environmental law expert Bernhard Wegener from the University Erlangen-Nürnberg also warns court cases could lead to a “chaotic” patchwork of individual decisions, instead of a unified government policy. But he adds: “That we have come so far is due to the failure of policymakers.”

More judges believe that executive and legislative aren’t doing enough

At the same time, there are more and more people in the legal system, and most importantly judges, who are ready to accept the human rights basis of climate change cases, and are prepared to issue instructions to governments to act. Urgenda legal counsel, Van Berkel pointed out that the European Convention on Human Rights was always intended to be a living instrument, reinterpreted in the context of a changing world. Michael Gerrard of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law agrees: “Of course no one person or company is responsible on their own but it’s the nature of the problem that it’s a collective responsibility. And there are good arguments that the law should be interpreted to impose obligations on everyone to protect humanity. These are not easy cases but several courts, most prominently the Dutch court in the Urgenda case but several others now, have found that these human rights theories do apply.”

Speaking to Clean Energy Wire, Joana Setzer, Research Fellow at the Grantham Institute reflected that “many judges a few years ago would say I can’t decide on this case because this is a matter for either the executive or the legislative, but now we see more judges who are accepting these cases and giving decisions that often will say the executive and the legislative are not doing enough. It has been a very recent change but I would suspect that, in the coming years, there will be more judges exposed to this issue and likely to be more convinced of its importance.”

—

Bonus Video added by Informed Comment:

Al Jazeera English: “Climate landmark: Court orders Royal Dutch Shell to cut emissions”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved