While the divestment movement is working to hold fossil fuel companies accountable, the World Bank is protecting and financing them.

By Manuel Pérez-Rocha | –

( Inequality.org) – At the international climate change negotiations in Scotland, the World Bank tried to position itself as a global champion in alleviating the climate crisis. In reality, this multilateral financial institution has been promoting and defending extractive and fossil fuel industries.

In a courageous column in the Guardian, one of the World Bank’s own researchers, Jake Hess, criticizes his employer for having spent more than $12 billion to fund fossil fuel projects since the Paris climate agreement in 2015.

“Sadly, I have little confidence that my employer will become a climate leader any time soon,” Hess wrote.

This is hardly surprising, given that Donald Trump picked current World Bank President David Malpass. Like the former U.S. president, Malpass has denied that human-produced carbon emissions cause global warming and climate change.

While the World Bank has continued to fund fossil fuel projects, many other institutions have pulled their money out.

A new report, “Invest-Divest 2021: A Decade of Progress Towards a Just Climate Future,” reveals that there are now 1,485 institutions in 71 countries publicly committed to fossil fuel divestment. The report is co-published by the C40, the Wallace Global Fund, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis and Stand.Earth and disseminated by the Dutch NGO Both Ends. The divesting institutions represent $39.2 trillion of assets under management.

“That’s as if the two biggest economies in the world, the United States and China, combined, chose to divest from fossil fuels,” the report notes.

Global inequality

Get the facts

The C40 coalition was founded in 2005 by the then Mayor of London, Ken Livingston, to build a collaborative network of mayors to deliver the urgent action needed to confront the climate crisis. Nearly 100 major cities now participate, including 14 in the United States, two in Mexico, and three in Canada.

This divest movement also includes grassroots environmental organizations, such as 350.org and Rainforest Action, and faith-based groups, including the World Council of Churches. In addition to the Wallace Global Fund, Ford, MacArthur, and other philanthropic foundations are also supportive.

This movement’s efforts to hold fossil fuel companies accountable for the true cost of their greenhouse gas emissions and in reducing their political power stands in stark contrast to the World Bank’s activities. Beyond their financial assistance for the fossil fuel projects, the Bank also house the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a tribunal where transnational corporations can file lawsuits against governments over actions — including environmental regulations — that reduce the value of their investments.

In another article, I argue that allowing corporations to keep filing these multi-million dollar lawsuits will potentially undermine the agreement reached in Glasgow.

Claims by extractive industries have increased exponentially during the last two decades. These companies were awarded at least $73 billion since 1995, according to my own calculations based on data available from ICSID and UNCTAD (and there are many other cases for which ICSID and other tribunals do not disclose any information).

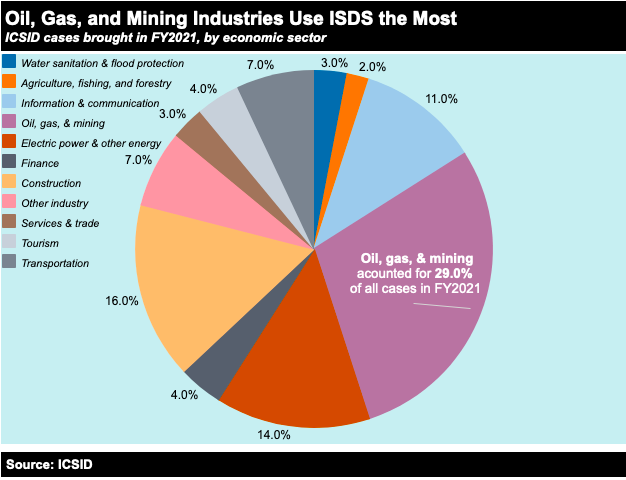

Extractive companies are the most frequent users of the investor-state dispute settlement system (ISDS), making up 29 percent of all ICSID claims in fiscal year 2021. They also obtain the largest awards. Of the 14 known rulings for more than $1 billion, 11 relate to the oil, gas and mining industries.

At least 82 lawsuits filed by extractive industries are still pending, among which 42 were filed by companies asking a total amount of $99 billion in compensation, according to the information available ($71 billion from mining companies and $28 billion from oil and gas companies).

It is worth noting that the amounts claimed for the other 40 pending lawsuits are not publicly available, therefore the above figures are merely illustrative of the magnitude of the problem. Notwithstanding the lack of information, it is possible to determine that at least 14 pending cases are demanding over $1 billion, including outrageous claims for $27 billion against Congo and $16.5 billion against Colombia.

Another case involves TransCanada against the United States. The Canadian company is demanding $16 billion in compensation for the Biden administration’s cancellation of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline. Of course, Mexico is part of the list, facing a $3.5 billion lawsuit by the U.S. company Odyssey Marine Exploration for the denial of a mining permit in marine sub-soils of the Sea of Cortez.

To effectively combat climate change, every government needs room for maneuver to be able to implement sound policies and climate actions without being blackmailed by costly corporate lawsuits. The investor-state lawsuit system must not stand in the way when it comes to addressing climate change and the civilizational threat it poses to the world.

By housing and supporting ICSID, the World Bank further tarnishes its credibility on climate change. But national governments are also at fault. They put the future of the planet at risk by turning a blind eye at climate summits to trade and investment rules (including the US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement) that reward polluting activities and protect the interests of extractive industries.

For now, the solution certainly lies in continuing to divest from planet-devastating extractive corporations.

Originally in Spanish in La Jornada

Via Inequality.org

Content licensed under a Creative Commons 3.0 License

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved