Ann Arbor (Special to Informed Comment) – A year ago, last September Jennifer Rubin wrote in the Washington Post:

“The wanton disregard for the lives of helpless citizens, for the fair application of the law and for our democracy is what we would expect in dictatorships around the world where might makes right.”

She was referring to the travesty of Breonna Taylor’s death and the failure of the justice system to recognize the value of citizens’ lives equally. In dictatorships legal justice is a privilege disbursed according to rank, with rank pegged to things like wealth, race, and religion.

Although unintended, Rubin’s description comes close to our current stereotype for a dictatorial China, both past and present, a nation where despots and their cronies lord it over the servile masses. But that is just a stereotype. In reality some laws in China were more egalitarian than those in America today.

How Imperial China Evened the Odds

For example, legal services were paid for by the state. From the 11th century onward, legal services were free for all taxpayers, so long as you weren’t gaming the system. That included farm women, who paid taxes, and so any rural woman could sue her neighbor, or a rich merchant, or even the magistrate himself.

European aristocrats knew better than to put legal power into the hands of commoners. In the 17th century, the Jesuit Louis Le Comte recalled how French litigants were required to pay “fees” to the judge, ensuring that the wealthier litigant would generally prevail.

He noticed that in China, by contrast “No fees are paid for the administration of justice . . . which empowers every poor man to prosecute his own rights and frees him from being oppressed by the opulence of his adversary.”

That is an odd sort of system for an empire bent exploiting the masses to prop up wealthy parasites.

In America today we might not pay judges directly, but the outcome is often determined by wealth. Think about it: what middle-class American could afford taking on the tech giants who daily violate their Fourth Amendment rights?

“That’s why we have elections” you might say, but a 2014 Princeton study showed that, in America, the electoral process more often results in legislation benefitting the wealthy, ignoring the wishes of the electorate as revealed in surveys.

That makes legal process the more effective method for seeking justice, but most citizens can’t afford the kind of legal muscle needed to challenge corporate opulence. Organizations like Common Cause or ACLU may help, but they can take on only the most egregious cases. For most, it’s pay-to-play.

A Battered Chinese Wife and Trayvon Martin

Another imperial Chinese practice was the assumption that legal precedent should apply equally in all cases. In theory our legal system works that way, but often precedents are applied differently depending on the racial, religious, or gender biases of juries.

Take a murder case from the 9th century. In that case, an ordinary taxpayer got into a fight with his wife and beat her to death. Her body was bruised all over and his wasn’t, so based on that and other evidence, the lower court argued it was murder and requested capital punishment.

Capital cases had to be reviewed by a higher court because “people’s lives are valuable”, another odd rule for an empire bent on exploiting the masses. In this case the higher court argued it was manslaughter: the two got into a fight, he hit too hard, but didn’t mean to kill her (details here).

Fortunately, there was another layer of checks, the anti-corruption department, and the relevant document survives. That officer supported the lower court’s decision. He argued that, if the higher court reading was allowed, in the future anyone could commit murder just by starting a fight, pulling out a weapon, and then killing the rival.

This might remind you of the Trayvon Martin case. George Zimmerman confronted the 17 year old Martin, and when Martin allegedly fought back, Zimmerman pulled a gun and killed him. Zimmerman was acquitted, but the jury doesn’t seem to have considered that their decision would serve as a precedent permitting a Black person to start a fight, pull a gun, and kill a white guy.

Equal application of the law was a major consideration in the Chinese case. Why didn’t the Martin Jury think of that?

I don’t know, but perhaps they understood that if a Black man picked a fight, pulled a gun, and killed a white man, his odds of being acquitted would differ from Zimmerman’s.

What about the Chinese case? The deadlock between the higher court and the anti-corruption department meant that the case had to go to the chief executive, the emperor. He sided with the officer’s argument, pronouncing against the male defendant, and providing justice for an ordinary woman taxpayer.

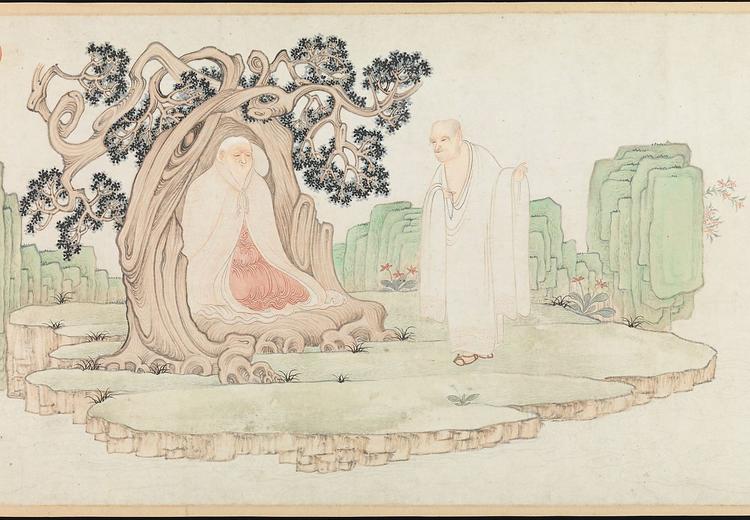

Wu Bin, “The Sixteen Luohans,” 1591, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Who Owns Justice?

All this might sound strange if you believe that the very notion of equality is a Western invention, but after 1615 Europeans were amazed to learn about egalitarian institutions in China. That was when Matteo Ricci’s description of China was published. In the same way they learned about religious toleration from European descriptions of Muslim practice.

Europe back then was far from democratic. According to Jonathan Israel, “The late eighteenth-century ancien regime world . . . was one ruled by princes and nobilities, and characterized by huge inequalities of wealth and legally buttressed privilege”.

It was a system bent on exploiting subjects to empower a privileged class of wealthy parasites.

Ricci explained that China didn’t have an aristocracy. Officers were expected to be competent and to work for the public interest. They took qualifying examinations anonymously to reduce the influence of race, religion, or family connections on the selection process.

Once appointed, performance was reviewed periodically. If caught, those guilty of corruption were barred from ever serving in government again. Ricci notes that corruption existed, but also described the elaborate system of checks, a novelty for his European readership. Period documents back up his claims.

Ricci’s letters went through sixteen editions in multiple languages in the space of a few decades. Towards the end of that century European thinkers began talking seriously about equality and toleration, often in direct reference to China and the Muslim world, straight through to the late 18th century.

After that, equality and toleration were dubbed Western concepts. China’s role in the rise of egalitarian practice, like Islam’s role in the rise of toleration, became victims of systemic racism in the Academy and in the media.

That is not to argue that equality is a Chinese idea. Frans de Waal showed that even monkeys have a sense of fairness, and every parent knows that children resent favoritism.

What China introduced was the notion that public benefit is the best standard of just government. Once that is in place, formal checks become a requirement.

What would checks check for? Competence and dedication to the public interest, but that is best determined by the facts of official performance. Facts are the ultimate check, without which three branches, five branches, or a hundred would be useless. That’s the reality standard, what Chinese political theory called shi.

That standard is one of China’s gifts to modern political theory. Without it, elections and litigation alike devolve into game shows.

But even a proper system of checks can fail. China’s first post-feudal dynasty collapsed within forty years. A Chinese historian, and friend of the anti-corruption officer we just met, blamed that collapse on the personalization of power.

So how do you prevent that? He recommended situating power in an office and holding the officer to his charge. Whether your political system has a parliament, a president, or a couple of Roman consuls, placing the powers of office in the office is the best way to prevent officers from treating their charge like a personal prerogative.

No One Has a Monopoly on Justice

What about China today? There was a time when legal pronouncements were made by radical mobs in thrall to the Great Leader Syndrome, the same syndrome that afflicts some Americans today. For those mobs, it was Mao that mattered, not the facts. You could call it populist, but you could hardly call it just.

More recently China has revived public benefit as the standard for just government, in part by rejecting those austerity policies so popular in the West. As a result China has done more to reduce poverty than any nation in memory.

China has also revived the anti-corruption department. Thousands of officials and CEO’s, high and low, have been jailed for corrupt practices, though the system sometimes fails dramatically, as happened recently.

China’s success in the future will depend on how consistently it can maintain egalitarian standards benefitting the general population rather than highly placed cronies. It’s anyone’s guess how that will play out.

Of course America has serious corruption problems too, and controlling them will be a challenge in a nation that the Centre for Systemic Peace classifies as an “anocracy”, part democratic, part autocratic.

As Adam Schiff explained during the Trump impeachment trial, some Congress persons think that being elected confers authority directly on the candidate, not the office. If you believe that, power becomes personalized in the officer. When that happens, officers feel free to rank personal interest over public benefit, leading to a political system “characterized by huge inequalities of wealth and legally buttressed privilege”.

So, no one has a monopoly on justice. Labeling America democratic because we hold elections or have juries doesn’t make the system just or fair. It might be someday, if legal services are equally accessible to all, if elections are determined by facts instead of emotions, and if officers are held to their charge.

President Biden’s Build Back Better Agenda and infrastructure law would in fact benefit the population as a whole—not to mention the planet—and his administration typically follows procedure and the law. Only one thing is missing.

Biden’s success, and America’s survival, may well depend on how effectively our officials are held accountable to their charge, and to the law.

Featured photo: Temple of Heaven, Forbidden City, Beijing. Taken March 2015. © Juan Cole.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved