By Aldert Otter | –

The Irish government signed up to the recent Glasgow Climate Pact and used the summit to announce a raft of ambitious goals, including the development of 5 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind energy up to 2030. That would more than double the country’s current onshore and offshore wind power capacity.

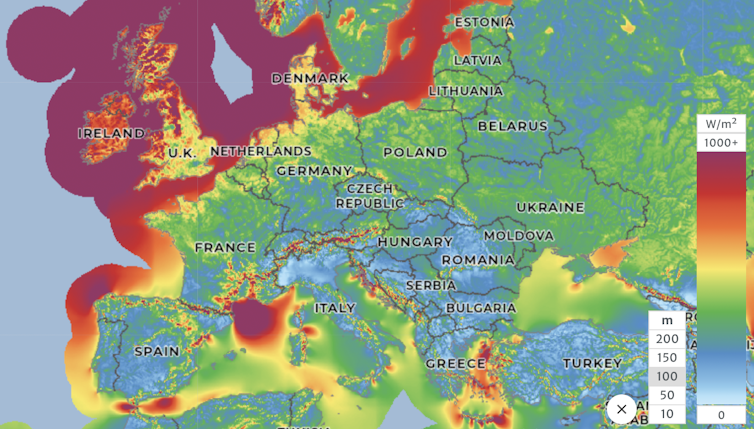

Compared to some of its more outlandish ambitions, such as having nearly a million electric vehicles on Ireland’s roads by 2030, the offshore wind target actually seems achievable. After all, the Republic of Ireland’s maritime area extends far into the Atlantic Ocean and is roughly ten times the size of its land area. The total offshore wind resource is enough to comfortably power the country’s electricity needs. Given more than 30 projects with a total capacity of around 29 GW are in various stages of planning, then it does indeed seem the 5 GW target can be reached by 2030.

Global Wind Atlas / DTU, CC BY-SA

However, the Irish government has a rather bad track record when it comes to delivering on climate plans and Ireland is currently one of the worst performers in the EU. Rewind back to COP21 in Paris, 2015. The then taoiseach (prime minister) Enda Kenny announced that “We have committed, with our EU partners, to a collective target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030”. With the same breath he then claimed it was okay if the national cattle herd would grow.

Six years on from Paris, optimistic projections show Ireland will only achieve a 24% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, even though a new target of 51% has been agreed. On the other hand, the national cattle herd has indeed grown, with agriculture now accounting for one third of the country’s total emissions.

Fianna Fáil: “Ireland’s future is in offshore wind farms”

Ireland stands to gain from offshore wind

The Irish offshore wind industry is still in its infancy, with the 24 megawatt Arklow Bank the only operating wind farm in Irish waters. But the country has a lot to gain. A growing offshore wind sector will help it achieve emissions reduction targets, and will also make Ireland less dependent on the import of energy and shield it against spikes in energy prices on the international markets.

mightymightymatze / flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Another benefit is that it will bring new jobs to coastal communities, which will help ease the energy transition. For example, as part of a large floating wind farm project off the coast of County Clare the Moneypoint coal power station is to be transformed into a green energy hub and manufacturing site for floating offshore wind turbines.

Gap between policy and action

But dark clouds are hanging over the Moneypoint project in particular, and the Irish offshore wind industry in general. In November 2021 Equinor, a Norwegian oil and gas giant, announced it was quitting its partnership in Irish offshore wind projects with ESB, an Irish electric utility company. One may question the motives of oil and gas companies for investing in offshore wind, but they are certainly capable of delivering badly needed investments. Part of Equinor’s reason was reportedly “dissatisfaction with Ireland’s regulatory and planning regime”.

The Irish government seems undeterred, saying that it was only one company abandoning the offshore wind market while many others are lined up to take Equinor’s place. The government intends to hold renewable energy auctions in 2022 and expects to see construction on offshore wind projects starting in 2025. However, both industry advocates and the government’s climate advisers warned this isn’t fast enough and that new legislation was needed to reform the planning and regulatory framework.

A Maritime Area Planning Bill passed into law in December 2021, which would suggest there is some movement on the legislative front. However, the Irish government admits there is still some work ahead to establish an Office of Marine Development Enforcement, develop necessary regulations, and get different state entities to agree on how to engage with the system.

In contrast, the UK government recently announced the development of an additional 12 GW of offshore wind energy. The Netherlands meanwhile, with a maritime area about 15 times smaller than that of Ireland, has announced the development of an additional offshore wind capacity of 11 GW by 2030, doubling its target, while construction of 2 GW is already ongoing.

Clearly Ireland is lagging behind other countries with offshore wind development. Ultimately, it is likely that many of the planned 30 projects will not be built, even with all the required legislation in place. However, at the current pace of legislation it is uncertain if even the 5 GW target will be achieved by 2030.

The coming year will reveal if the Irish government is indeed serious about offshore wind energy by delivering the necessary legislation, and hopefully avoiding another debacle like the Equinor departure.

Aldert Otter, PhD Researcher, Marine and Renewable Energy Ireland, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved