Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Christoph Duenwald et al. at the International Monetary Fund have a new report out that finds that temperatures in the Middle East and Central Asia have already risen by 2.7 degrees F. (1.5C) over the past century, at a rate twice as fast as that of the rest of the world.

Temperatures are rising because humans have pumped billions of tons of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution, by burning coal, methane gas and petroleum. We heat up the earth every time we drive our internal combustion engine car or heat our houses with coal or methane gas.

The Greater Middle East (including Afghanistan and Pakistan) is being hit even harder than Central Asia (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan.

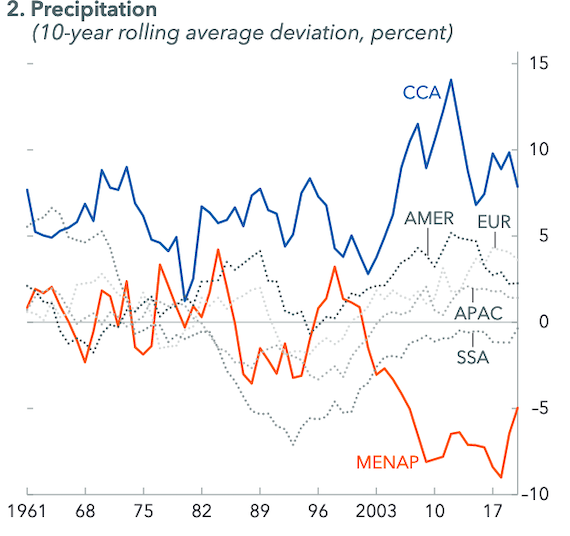

And that is only the beginning of the bad news. They say that precipitation in this already-arid region is becoming even more erratic. In an arid zone that stretches from the Sahara to the Gobi desert, you never want to hear that rain is even scarcer than ever before. The erratic rainfall means sometimes it doesn’t come, sometimes it comes in spades. So you have more frequent droughts, but also more frequent floods than were common a century ago.

The decline of annual rainfall in this region is apparent from this World Bank/ IMF chart, included in the report. The orange line is the Middle East and Central Asia:

We have already seen major water riots in Iran in the past year, with people protesting police action against the “innocent and thirsty people” of Khuzestan and chanting “the mullah must go,” referring to clerical Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

In drought-stricken parts of Syria in the past decade, radical groups are said to have recruited by supplying food to families affected by the lack of water. So these climate changes can contribute to radicalization.

The IMF authors write, “Recent decades have seen numerous flash floods in MENAP’s arid/semi-arid zones (Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia), cyclones in the Horn of Africa, and riverine flooding and landslides after heavy rain and snowmelt in the mountainous CCA (especially Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan.”

Since the year 2000, the authors say, the region has experienced $2 billion annually in costs because of extreme weather events.

Increased temperatures and changing patterns of rainfall, they say, have actually driven down people’s personal incomes during the period since 1990.

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan are especially vulnerable to these changes, they say.

The Middle East and Central Asia are getting hotter and poorer. That’s a recipe for volatility in a region that in recent years has already seen a lot of political volatility.

In fact, those countries that are already conflict-ridden, such as Iraq, Syria, Somalia and Libya, will have the most difficulty dealing with these changes. Kinda reminds you of what somebody from that region once said: “I tell you, that to every one who has will more be given; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.” (Matt. 25:29).

Let’s say humanity can keep global heating to 3.6 to 5.4 degrees F by 2100 (2-3C). That isn’t the best scenario but it is better than some worse ones. Under this “moderate” rise in temperatures, the cost to society and the economy of all the extra deaths that will ensue would be so severe that it could reach 1.6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the middle decades of our century.

Most countries only grow their GDP one or two percent a year, so the IMF seems to be saying that they would be plunged potentially into a long period of economic stagnation because of all these extra deaths caused by high temperatures, droughts, floods, cyclones and so forth.

The report emphasizes that countries in the region must take steps to remain resilient in the face of these challenges. They need better water management, for instance. This is a very useful way to think of the crisis. It is a challenge, which can be met in various ways by good governance. But if it is not, the effects will be even more devastating — and destabilizing.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved