Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Ben Storrow of Climate Wire tweeted this week that “Last Tuesday, total U.S. wind generation exceeded 2,000 GWh, making wind the second largest producer of electricity in the United States after natural gas for that 24-hour period. Did a quick look at EIA’s numbers going back to 2018. Don’t think that’s ever happened before.”

Storrow notes that wind power in the US has occasionally bested coal, but not both coal and nuclear.

Last Tuesday, total U.S. wind generation exceeded 2,000 GWh, making wind the second largest producer of electricity in the United States after natural gas for that 24-hour period.

Did a quick look at EIA's numbers going back to 2018. Don't think that's ever happened before. pic.twitter.com/VW7YSPK6LJ

— Ben Storrow (@bstorrow) April 4, 2022

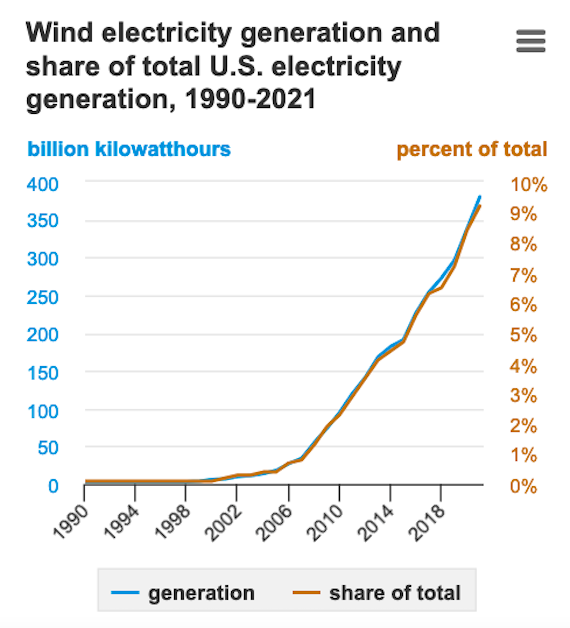

That milestone was a one-day phenomenon. On most days, wind would still come in below the fossil fuels and nuclear. Only 9.2% of US electricity comes from wind turbines.

That this record could be achieved points to the future, since the US is installing more and more wind turbines, whereas half of the 240 US coal plants are scheduled to be closed by 2030.

Yale Climate Connections reports that 12.6 gigawatts of coal capacity are expected to be retired in 2022.

But, at the same time, the Energy Information Agency says that some 21.5 gigawatts of new solar generation will come on line along with 7.4 gigawatts of new wind.

According to John Fitzgerald Weaver at PV Magazine, the Ember energy think tank recently calculated that if wind and solar go on growing by at least 20% a year globally, that growth in renewables would assure the world can stay below an extra 1.5 degrees C. of heating (2.7F), which the goal of the Paris Climate Accords.

h/t US Energy Information Agency.

Climate scientists worry that if we heat the earth beyond 2.7 degrees F. above the pre-industrial average by burning gasoline, coal and methane gas, the earth’s weather systems could become chaotic.

In two decades, US wind power has increased 113 times. That’s times, not percent. It has gone from “6 billion kilowatthours (kWh) in 2000 to about 380 billion kWh in 2021” according to EIA.

In new US wind turbines, the average nameplate capacity is 2.75 megawatts. That is up 284% since the beginning of this century. It is even up 8% from 2019. So the turbine capacity is growing with head-spinning speed.

The Department of Energy informs us that “Wind provides more than 10% of electricity in 16 states, and over 30% in Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and North Dakota.”

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved