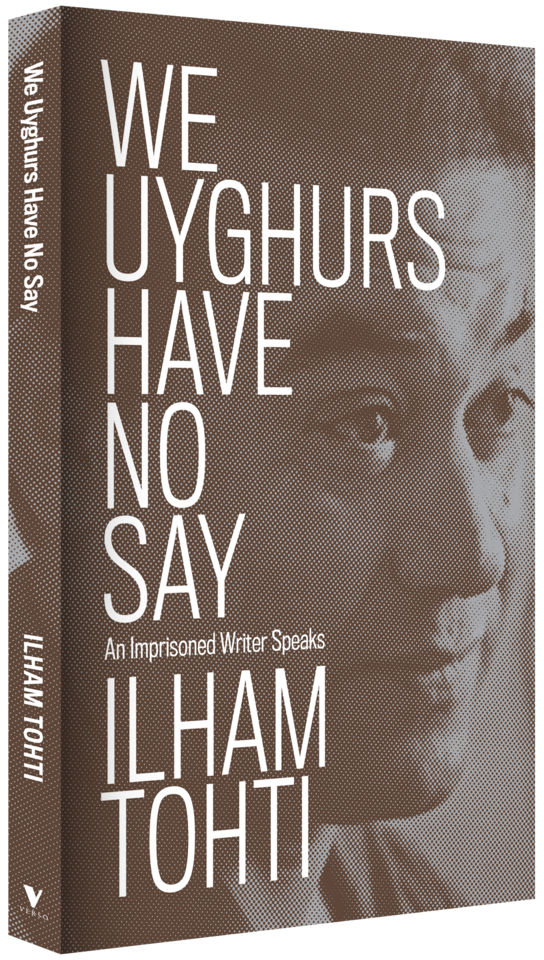

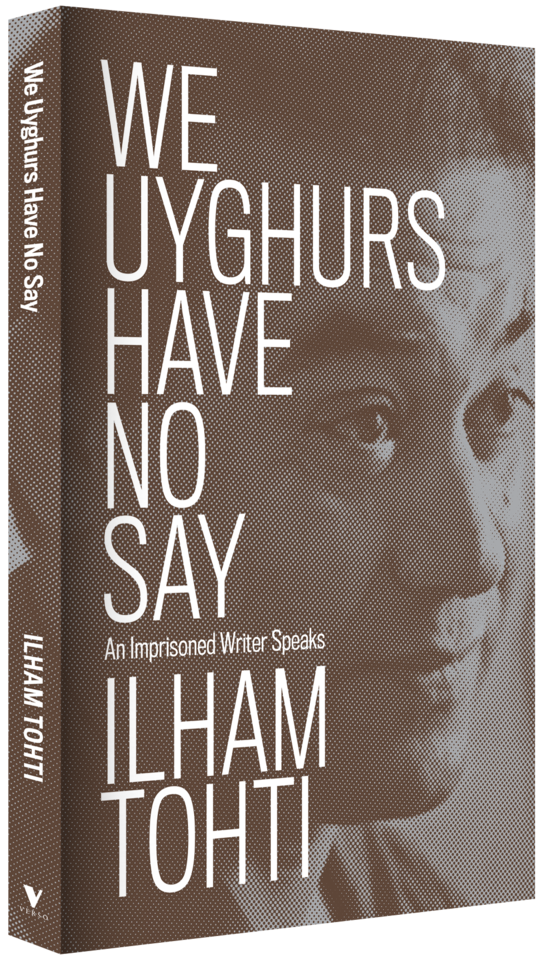

Tuebingen (Special to Ann Arbor) – Review of Ilham Tohti, We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks (London: Verso, 2022).

Ilham Tohti, a Chinese intellectual and advocate for the rights of the Uyghurs, the Muslim minority group he belongs to, was jailed in 2014 by the Chinese government. Little has been known about him since he was given a life sentence on charges of “separatism.” According to his daughter, Jewher Ilham, the family of the Uyghur scholar has not received any information about him since 2017.

The Chinese government may be determined to silence Ilham Tohti’s voice at any cost, but the recently published book We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks pursues the opposite objective: providing a platform for the Uyghur scholar’s research and reflections to be read and debated. The book includes a collection of Tohti’s articles, essays, and statements spanning the 2005-2014 period translated into English for the first time (the translators are Yaxue Cao, Cindy Carter, and Matthew Robertson) as well as several interviews granted by the author to international media before being detained. Furthermore, We Uyghurs Have No Say serves an additional function. It compiles several texts that, as Senior Lecturer in East Asian History at the University of Manchester Rian Thum explains in the preface of the book, are “no longer publicly available.”[1] Many of these articles were originally published on the website Tohti created to discuss issues concerning the Uyghurs, uighur.biz.

Ilham Tohti, We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks. Ciick here.

Tohti’s writings dissect the main problems faced by the Uyghurs in modern China. The Uyghurs, who speak a language similar to Turkish and number around 12 million, are mainly Muslim and live in the northwestern region of Xinjiang. Due to the mass state-orchestrated migration of Han Chinese (China’s ethnic majority) to Xinjiang, the Uyghurs now make up less than half of Xinjiang’s population. When the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, the Uyghurs still represented 80% of the province’s population according to the figures presented by Tohti.[2] Xinjiang is a region rich in raw materials used to produce solar panels and has vast reserves of oil, gas, and coal.

Tohti explains how the job market in Xinjiang privileges the Han over the Uyghur and other smaller minorities living in the area – such as the Kazakh, the Hui, the Mongols, and the Kirghiz. The Uyghurs are traditionally employed in the rural economy of southern Xinjiang, which is less economically developed than the northern areas of the province, where most Han live. There are severe restrictions for the southern Uyghurs who decide to migrate to the north. Moreover, both the civil service and state-owned enterprises are responsible for what Tohti describes as “blatant ethnic discrimination in hiring.”[3] Particularly since the 1990s, Uyghur governmental cadres have experienced a decrease in their status and responsibility within the state structure. As Tohti explained in 2013, “Uyghurs have been excluded from the center of power, and their political stature in China is in sharp decline.”[4]

The Uyghurs have also seen their linguistic rights repressed. Tohti denounces how a theoretically bilingual education system – teaching both Mandarin and Uyghur – is actually a monolingual system in which the Uyghur language is sidelined. Regarding religion, and contrary to what it claims, the Chinese government goes far beyond combating religious extremism. Tohti describes Beijing’s policy on the topic as “opposing religious tradition and suppressing normal expressions of religious belief.”[5] The Chinese government has banned Muslim names as well as Ramadan fasting and headscarves. The consequence of this crackdown on religious freedom, notes the Uyghur scholar, has been an increase in religious radicalism.

Ilham Tohti does not content himself with identifying the main problems regarding Beijing’s policy towards the Uyghurs but puts forwards proposals on how to address them, such as the fostering of integration and social contact between Han and Uyghur. His suggestions are by no means radical, which makes all the more obvious that the Chinese government’s decision to imprison Tohti derives from its almost non-existent tolerance for criticism. As Rian Thum has noted, Tohti’s writings do not challenge the “ideological foundations of the People’s Republic or the legitimacy of Chinese rule in Xinjiang.”[6] Tohti has clearly stated that his desire for the Uyghur people is “ethnic autonomy inside China.”[7] According to him, this would not necessitate the introduction of a new legal framework but the application of the already existing one. The Uyghur scholar explains that the 1984 Law of the People’s Republic of China on Regional Ethnic Autonomy “provides sound legal foundations for regional ethnic autonomy in China.”[8] James A. Millward, a China scholar at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, puts it succinctly, “Tohti pointed out that China’s own existing laws could protect minority cultures – if only they were observed.”[9]

Tohti defines China’s state policy towards the Uyghurs as “ethnic apartheid” and remarks that this system of segregation calls to mind similar cases such as Palestine.[10] The similarities between Palestine and Xinjiang are multi-faceted, but probably the most remarkable one is that both have been at the receiving end of settler-colonialist projects. As Patrick Wolfe argued in his seminal article on settler-colonialism, the core of a settler-colonial project is “the dissolution of native societies” and the establishment of “a new colonial society on the expropriated land base.”[11] In Xinjiang, “Uyghur farmers and subsistence herders are encircled by Han settlers who, attracted by profit-making enterprises, now constitute nearly 90 percent of Xinjiang’s urban population.”[12]

Sean R. Roberts, the author of the book “The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Campaign Against Xinjiang’s Muslims”, has described Beijing’s policy towards the Uyghurs as being dominated by the racist logic of settler colonialism. The “Han-dominated state’s settler colonization aspirations”, argues Roberts, are partly responsible for the increased level of repression China has been applying to the Uyghurs since 2014.[13]

2014 was the year of Tohti’s imprisonment and, probably not coincidentally, also the year when the Chinese government launched its “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism” in Xinjiang. In his 2014 visit to the northwestern province, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that the Chinese Communist Party “must not hesitate or waver in the use of the weapons of the people’s democratic dictatorship” against what he called the forces of religious extremism. Xi’s speech paved the way for a massive repressive campaign in Xinjiang, which saw the number of people formally arrested increase threefold. The Chinese government has opened large detention camps where the Uyghurs and other minorities living in Xinjiang suffer from torture and mass indoctrination. Prisoners have also been subjected to forced sterilization and forced labour. Meanwhile, life outside the camps presents its own forms of repression. Beijing has established a system of mass surveillance and police presence in Xinjiang that monitors the movements of the Uyghurs through facial recognition technology, mandatory check-ups, and the confiscation of mobile phones and passports.

As we have seen, the situation of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang has quickly deteriorated since Tohti’s detention in 2014. The root causes of everything that has happened since Tohti was jailed, however, are all intelligently examined in We Uyghurs Have No Say. The Chinese government decided to ignore Tohti’s moderate calls for reform in Xinjiang. Tohti’s imposed silence embodies the Uyghurs’ current tragedy.

[1] Rian Thum, “Preface: Ilham Tohti and the Uyghurs,” in We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks (London: Verso, 2022), p. xv.

[2] Ilham Tohti, We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks (London: Verso, 2022), p. 21

[3] Ibid., p. 55

[4] Ibid., p 83

[5] Ibid., p 71

[6] Quoted in Alexa Olesen, “Angry Minority Finds a Voice on Chinese Campus,” Newsday, January 3, 2010, https://www.newsday.com/news/world/angry-minority-finds-a-voice-on-chinese-campus-o09733.

[7] Tohti, We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks, p. 168.

[8] Ibid., p. 108.

[9] James A. Millward, “China’s Fruitless Repression of the Uighurs,” The New York Times, September 28, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/29/opinion/chinas-fruitless-repression-of-the-uighurs.html.

[10] Ibid., pp. 78-79

[11] Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 388.

[12] Aidan Forth, “Settler Colonialism Meets the War on Terror: The Enclosure of China’s Uyghurs,” Los Angeles Review of Books, November 8, 2021, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/settler-colonialism-meets-the-war-on-terror-the-enclosure-of-chinas-uyghurs/.

[13] Björn Alpermann, “Book Review – The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Internal Campaign against a Muslim Minority,” Politics, Religion & Ideology, 2022: 2.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved