By Atal Ahmadzai

( Foreign Policy in Focus) – In the year since the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan has endured rapid and agonizing setbacks. Two decades of socio-economic and political gains have vanished under the dystopian rule of the Taliban. Furthermore, while peace is far from being realized, political violence, including the Taliban’s extrajudicial executions, jihadi terrorism, and armed resistance to the Taliban, is intensifying. However, a more consequential impact of the Taliban regime is the growing ethnic divide in the country. Will the repressive rule of the predominantly Pashtun Taliban lead to the Balkanization of multiethnic Afghanistan?

In 2010, then-U.S. Special Representative to Afghanistan Richard Holbrooke, a seasoned American diplomat, described the ethnic power base of the Taliban insurgency among the country’s Pashtun population as one Talib in almost every Pashtun household. The Obama administration rebuked the remarks as it stirred controversy with the Afghan government and some Pashtun elites. Nonetheless, as one of the Dayton Accords architects, which ended the multiethnic war in Bosnia in 1995, Holbrooke was well-informed on the ethnic dynamics of armed conflicts in multiethnic societies like Afghanistan.

The logic behind the claimed association between Pashtuns and the Taliban is simple: Taliban are predominantly Pashtuns. Although it does not imply that most Pashtuns are Taliban or that the Afghan conflict has an overriding ethno-sectarian nature, the common ethnic factor has certainly fostered support for the Taliban insurgency among Pashtuns. Moreover, Pashtuns appear to have remained complacent toward the Taliban regime in Kabul. Such support and complacency may have various reasons, but two are at the forefront: ethnonationalism and social transformation.

Afghanistan is a multiethnic country with undeniable subnational tribal and ethnolinguistic allegiances. Such loyalties unseat the prioritization of citizenry and collective identity imperatives in domestic politics. Although because of their radical Islamic ideological orientation the Taliban denounce nationalistic socialization, their ethnic identity has gained them the support of rural Pashtuns. Likewise, their ethnicity also caused the Taliban constraints in extending influence in non-Pashtun areas. Essentially, ethnonationalism partially drives both patronage and resistance toward the Taliban.

Taliban support among rural Pashtuns also has an ideological base that is shaped by the social transformation induced by the decades-long conflict. Though it has transpired across Afghan society, the transformation is more consequential in the Pashtun social setup. The continued and unwavering spread of the Deobandi and Wahhabi madrasa systems across the Pashtun belt along the Afghan-Pakistan border since the Afghan jihad in the 1980s has played an instrumental role in shifting Pashtun society from its egalitarian nature towards religious fundamentalism. With the decay of Pashtunwali, the customary Pashtun code of conduct, religious fundamentalism has replaced the traditional social structure of the Pashtuns, which subsequently raised radical religious figures to positions of power and social control.

During the insurgency, most of the rural Pashtun population was under the direct or indirect influence of the Taliban. Consequently, they remained deprived of developmental opportunities offered by the Afghan government and/or the international community. By inducing grievances against the state, such deprivation enabled the Taliban to further expand their base and reinforce social control in Pashtun-dominated areas. Although Pashtun support for the insurgency was crucial for the collapse of Kabul, their complacency with the Taliban regime widens ethnic divisions in the country.

The immediate impacts of the Taliban regime’s draconian rule are even more substantial among the urban population and non-Pashtuns. During the 20 years of international development assistance, Afghans living in urban centers and non-Pashtun areas effectively advanced their individual and collective developmental goals. The regime’s war on liberties and fundamental rights, including girls’ education and women’s employment, is more palpable among these social groups, thereby increasing the likelihood of potential reactionary armed or non-armed resistance.

Since the Taliban’s rise to power, opposition has emerged largely along ethnic lines, and non-Pashtuns are fostering their resistance. The launch of the National Resistance Front (NRF) against the Taliban and the revolt of Uzbek and Hazara elements within the Taliban are examples of such resistance. The NRF, still in its infancy, is a predominantly non-Pashtun force in northern Afghanistan. Although the resistance is not against the Pashtuns, the predominant Pashtun composition of the Taliban can automatically reshape the conflict along ethnic lines. The question is whether the conflict will transform into a full-blown ethno-sectarian one with the potential of progressing to the balkanization of Afghanistan.

Ethno-sectarianism was never the dominant attribute of the Afghan conflict and has remained secondary to ideological drivers. However, with the Taliban in power, the increasing ethnic-based grievances can bring ethno-sectarian factors to the forefront of the conflict. A largely non-Pashtun resistance to the predominantly Pashtun Taliban can escalate into an ethnic-based conflict unless either the Taliban regime transforms into a broad-based inclusive government or rural Pashtuns participate in the anti-Taliban resistance. Both scenarios seem unlikely, however.

The Taliban’s radicalism, internal power dynamics, and continued ties with global terrorism will prevent them from shifting into the mainstream. During their 20 years of insurgency, the group systematically embraced extremist ideologies and practices, including but not limited to Takfiri ideology,

Rural Pashtuns are unlikely to rise up against the Taliban, mainly due to the limited impact of the Taliban’s repression on their lives. For years, the Taliban insurgency was concentrated in the Pashtun-dominated provinces, which deprived the population of development and progress. Furthermore, to deepen their social control, the Taliban insurgency strategically weakened the traditional social structure of the Pashtuns, including targeting their elites and elders. Hence, the current despotic regime of the Taliban and its strangulation of liberties and freedoms are neither new nor sufficiently life-altering for rural Pashtuns to incite resistance, at least not yet.

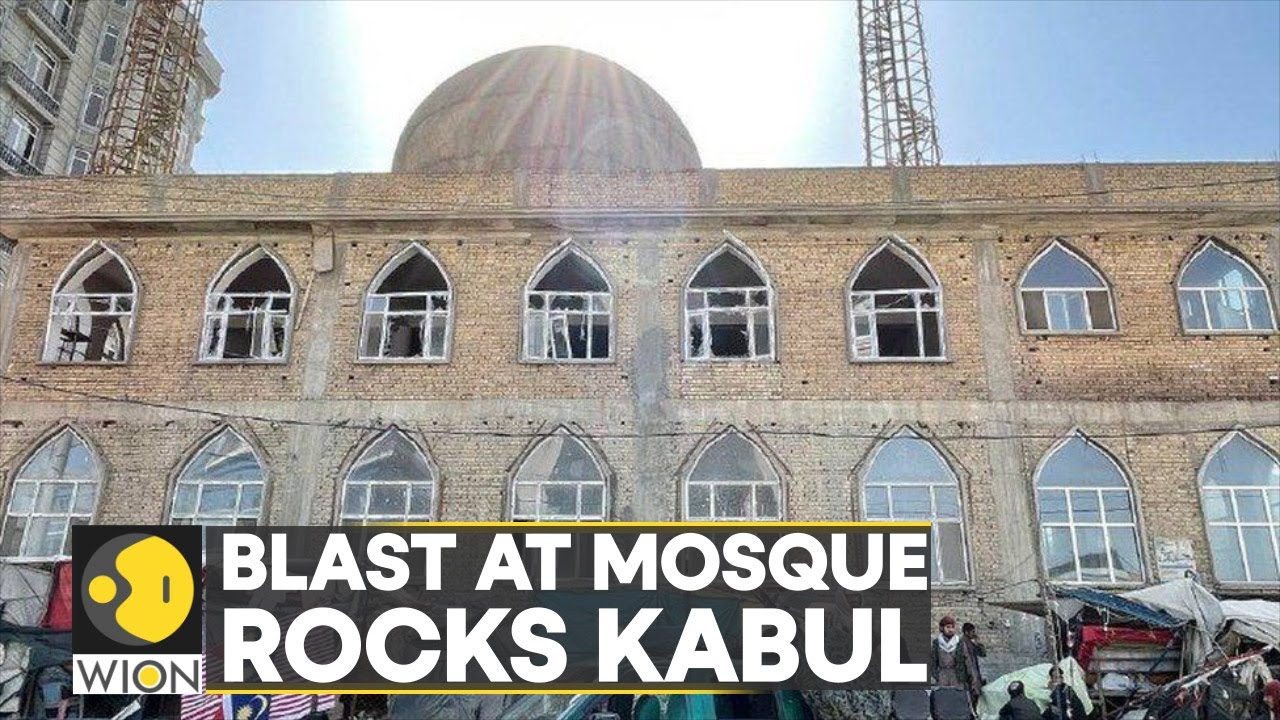

The continuation of the Taliban regime in Kabul will keep widening ethnic grievances in the country. Its potential escalation to an ethno-sectarian conflict will have strategic ramifications, including the growth of global terrorism and the strengthening of the Taliban. Generally, ethnic conflicts provide a conducive environment for terrorism to grow. Practically, to counterbalance the power of the Taliban, the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (IS-K) has reportedly begun recruiting Tajik and Uzbek fighters in northern Afghanistan. Furthermore, increasing ethnic grievances and the repression of the Taliban can attract some anti-Taliban, non-Pashtun militants to other forces like the IS-K.

Strategically, two initiatives can prevent the escalation of an ethno-sectarian conflict. First, the anti-Taliban armed resistance can be strengthened by diversifying its ethnic base, mainly with Pashtun resistant fighters. Secondly, the anti-Taliban, non-armed struggle among Pashtuns can destabilize the Taliban’s ethnic power base. Revitalizing support (covert and overt) to civil society and echoing its voice will challenge the Taliban’s rhetorical and deceptive claims of change and political legitimacy on the international stage. Humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan should go through a strictly observed, UN-coordinated mechanism that ensures that the aid goes directly to the people. Observations from the field suggest that the Taliban either misappropriate international assistance as salaries for government officials or distributes it to its fighters. But with monitoring, Afghanistan’s own assets, now frozen in U.S. accounts, can return to the country in a decentralized manner and help the people who need it most.

In long run, incorporating considerations about a decentralized state model for any future political settlement for the country is of strategic significance. Centralization in Afghanistan always carries the potential to encourage repressive forces to exert their power, will, ideology, and authority over others with a different socialization. Fundamentally, centralization has impeded the evolution of effective state machinery and institutionalization in the country.

The failed international state-building efforts in Afghanistan indicate the structural dysfunctionality of the centralized state. Historically, effective centralization in Afghanistan was attained only through suppression. Moreover, the current Taliban regime further delegitimizes political narratives of centralization. No cause, divine or nationalistic, should serve to justify the government’s repression of people and regions with distinctive ethnolinguistic and social characteristics.

On the contrary, for the institutional and structural functionality of the state, a decentralized political arrangement seems unavoidable. Distinct regions should exercise authority in deciding the rights and security of their residents and should have an active role in determining issues that have direct impact on the lives, livelihoods, and lifestyles of local communities. Otherwise, a centralized political system will always carry the risk of encouraging forces with a dystopian outlook like the Taliban to repress those who do not mirror themselves. Although the disintegration of Afghanistan may seem farfetched, the decentralization of its political setup appears inevitable.

Atal Ahmadzai is a visiting assistant professor of international relations at the Department of Government, St. Lawrence University in NY. As a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Arizona, he studied the governance systems of violent non-state actors in South Asia. Born and raised in Kabul, he has over ten years of research experience in studying terrorism. His work appeared in academic journals, including Perspectives on Terrorism. He also published short analyses in Foreign Policy magazine, the Conversation, and Political Violence at a Glance.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved