By Sydnee Wilson | –

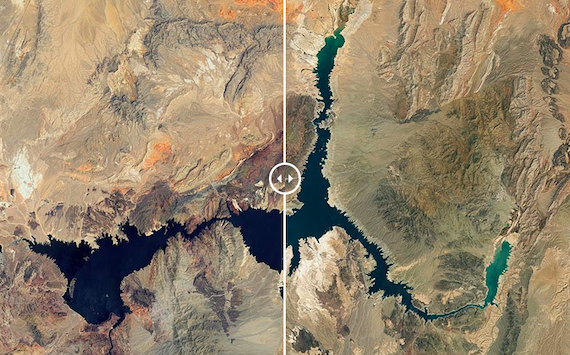

( Cronkite News) – PHOENIX – NASA satellite photos show how drastically the water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead have receded in just the past few years. They demonstrate the severity of long-term drought and the challenges Arizona will face to conserve and enhance its precious water supply.

Susanna Eden is the research program manager for the Water Resources Research Center at the University of Arizona. She has been with the center for 17 years and has researched water policy and management even longer. The NASA images are shocking, she said, and should concern Arizonans.

Satellite images from NASA show how water levels have dropped over time at the nation’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, and at Lake Powell, which straddles the Arizona-Utah line. The Lake Mead images taken, July 6, 2000, left, and July 3, 2022, right, demonstrate the impact of climate change and ongoing drought throughout the West. (Photos courtesy of NASA)

“They are very stark images,” Eden said. “People should recognize that it’s not a disaster yet, but it’s getting close.”

She also said people may have a false sense of security when it comes to tackling this issue.

“We tell ourselves that we are in a good position because of our technology and because of our abilities to control nature and our actions,” Eden said. “We tell ourselves that we’re not going to go the way of civilizations that disappeared because of drought. But we are challenged.”

To help meet those challenges, the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Central Arizona Project are negotiating with California and Nevada to find a way to meet water demands after the federal government in August ordered further cuts to water delivery in the Colorado River Basin.

As Lakes Mead and Powell shrink – both reservoirs are about 25% full – remnants of life before the drought have begun to resurface. The reduced water levels in Mead have revealed sunken boats, landing vessels from the World War II era, and human remains of a murder victim from more than 50 years ago. Long-hidden natural wonders, including Lake Powell’s Gregory Natural Bridge, also have come to light.

The receding reservoir levels – which threaten water for agriculture, people and hydropower – are the result of a megadrought that has gripped the Southwest for more than two decades. It’s extremely rare in the climatological record – the kind of drought that causes upheaval and major change, Eden said.

The U.S. Drought Monitor, which updates weekly nationwide, shows all of Arizona in drought. Some areas of Mohave Valley near Lake Mead are in extreme drought, and the area closest to Lake Powell in Coconino County is in a severe drought.

In August, the Bureau of Reclamation implemented a 24-month operation plan to reduce releases at Glen Canyon Dam, which forms Lake Powell. The move will keep about 1 million acre-feet in Powell by next April.

In June, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton gave the Basin states until mid-August to propose a plan to keep an additional 2 million acre-feet of water in the system, but that didn’t happen so the federal government stepped in.

In a statement last month, the state water department and the Central Arizona Project – which delivers Colorado River to the state – said Arizona has carried a disproportionate burden of water reductions and a future plan will need to be more equitable for the state.

The Drought Contingency Plan developed in 2019 by Arizona, Nevada and California outlines that Arizona gets 592,000 fewer acre-feet of water from the Colorado River starting next year. In comparison, Nevada only has to cut 25,000 acre-feet and California doesn’t have any reductions.

“We want to spread the pain,” said Doug MacEachern, communications administrator for the Department of Water Resources. “Arizona already is leaving around 800,000 acre-feet of its allocation in the system now this year alone, and in large part that is water that formerly went to farmers.”

Arizona agriculture uses 74% of Arizona’s water supply, so farmers bear the brunt of the reductions. If Arizonans don’t act now, MacEachern said, the whole country will feel the impacts of these cuts in the future.

Water levels at Lake Powell have dropped so low that natural wonders are starting to reappear, including Gregory Natural Bridge, which hasn’t been seen since the Colorado River reservoir was filled in the 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Eric Hanson)

“We have to be conscious of the fact that 90% of North America’s leafy green vegetables come from farms in Arizona in the wintertime,” he said. “Without water to irrigate that land, the entire country will be seeing and probably feeling that impact because they won’t have that lettuce they come to expect on their table in the wintertime. There are impacts going forward that we’re all going to have to deal with.”

The effect of the megadrought could be catastrophic and water users need to think long-term about how to best conserve dwindling water supplies.

“Pretty much every community in the Phoenix area is in at least stage one of their drought plans, and that requires, generally, that certain areas along roadways aren’t watered or watered less than they would have been otherwise,” MacEachern said. “It hasn’t set a really demanding stage, but the likelihood of cities going deeper into their drought plans is real.”

Cynthia Campbell, the water resources management adviser for Phoenix, said the city is in stage one of its drought management plan. In stage one, she said, “we try to inform and educate our customers as much as we possibly can, in an intensive way to make sure that folks are aware that there is an issue.”

Campbell said the drought isn’t a crisis for the city. Phoenix gets 60% of its water from other sources, such as snowmelt from the far north and east of the Valley, and through the Salt River Project, and the city has long had water conservation efforts.

“If things get more significant in terms of the cuts, which no one really knows, at this point, when or if that will happen, then we absolutely have those tools in the toolbox to include curtailing use,” Campbell said.

Related story

Angry at other states, Arizona towns, tribes rethink planned water cuts

Those tools include water rebate programs, increasing landscaping efficiency and a cooling tower program that recycles water, Campbell said. Phoenix also will follow its Drought Management Response Procedure, which has four stages, ranging from education and voluntary water reductions to mandatory reductions and fines for overuse.

Water cuts and conservation can help address a megadrought, but they may not be an adequate long-term solution. Eden said conservation by the public is only part of the answer.

“People who control large amounts of water or who have a major say in … large amounts of water need to realize that things can’t go on the way they have been up to now,” Eden said. “Major sacrifices have to be made. That is one of the things that I would advocate along with investigating and investing in all the kinds of technological and infrastructure options of reuse, desalination (of seawater) and stormwater capture.”

The NASA images, released in July, indicate a bleak future for Arizona water, but Eden remains hopeful. As long as Arizona and the other six Basin states build a comprehensive plan and begin to conserve water, she said the water crisis will end.

“I’m pretty optimistic about the future of Arizona water,” Eden said. “I believe that we can get through this crisis and go through another potentially long period of sufficient water. We can put our minds together and come up with solutions for really long-term issues or the change in climate.”

Sydnee Wilson expects to graduate in May 2023 with a bachelor’s degree in journalism and mass communication. Wilson has interned with Phoenix Magazine and written for the Peoria Times and HerCampus ASU.

Payton Major expects to graduate in May 2023 with a bachelor’s degrees in broadcast journalism and meteorology, as well as certificates in GIS and atmospheric sciences. Major has interned with CNN Weather and MadridMedia and works for WeatheRate and the Arizona Climate Office.

Via Cronkite News

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved