By Mathieu Blondeel, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick | –

The burning of fossil fuels caused 86% of all CO₂ emissions during the past ten years. Despite being the primary culprits of global heating, coal, oil and gas were barely mentioned in the official texts of previous UN climate change summits.

That all changed at COP26 in November 2021, where the Glasgow climate pact was signed. The agreement contained the first ever acknowledgement of the role of fossil fuels in causing climate change. It also urged nations to phase out measures which subsidise the extraction or consumption of fossil fuels and to “phase-down” coal power.

With COP27 beginning in Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt, it’s time for a progress update. Unfortunately, it’s not good news. The ongoing energy crisis – and the short-term responses to it by governments around the world – have made it more difficult to meet the pact’s goals of ending the dominance of fossil fuels.

The global energy crisis

The current predicament is probably the first of its kind in which prices for all fossil fuels have soared simultaneously. This has hiked electricity prices in turn.

Europe has had to rapidly adjust to Russia using its gas exports as a weapon since its invasion of Ukraine. As the Kremlin cut pipeline gas supplies, European countries rushed onto the global market for liquified natural gas (LNG) and increased imports from traditional partners such as Norway and Algeria.

This has raised natural gas prices to dizzying heights and created a global scramble for gas in which Europe can outbid developing economies for essential LNG shipments, pushing countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh deeper into crisis.

To keep the lights on, some of these developing economies are resorting to the most polluting of all fossil fuels: coal. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects that in 2022, global coal consumption will match its all-time high of 2013.

In the EU, demand for coal (primarily from the electricity sector) is expected to rise by 6.5%. If current demand trends continue, global coal consumption will only be 8.7% lower in 2030 than what it was in 2021. To reach net zero emissions by 2050, this should be 32% lower.

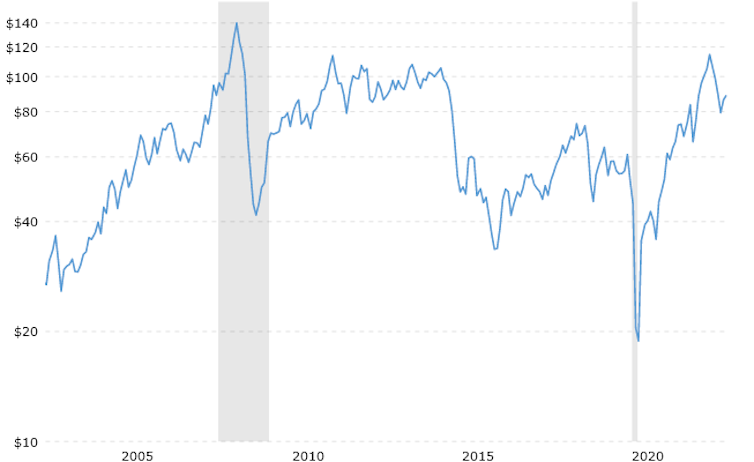

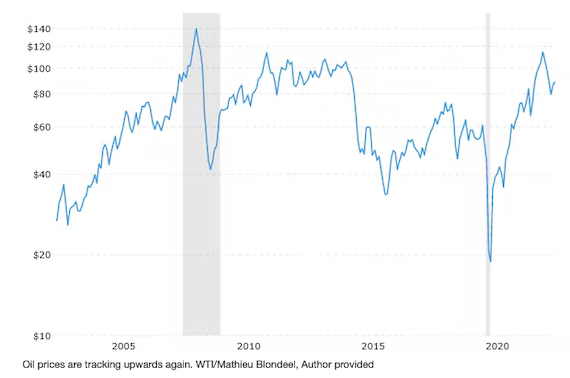

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies (OPEC+), most notably Russia, recently decided to slash oil production by 2 million barrels a day in a bid to hike oil prices. Although OPEC+ justifies its decision by saying that it is anticipating a global recession that could herald a replay of the oil price crashes of 2008, 2014 and 2020, the EU and US have slammed the move as politically-motivated.

WTI/Mathieu Blondeel, Author provided

To bring down high fossil fuel prices, governments globally are resorting to the very subsidies they agreed to phase out. These subsidies cut fuel costs for consumers by fixing the price at petrol pumps, for example.

After a noticeable dip in 2020, fossil fuel subsidies expanded in 2021. The energy crisis has prompted another sharp increase according to IEA estimate for 2022. In the past, developing economies were criticised for using these fiscal tools, not least for subsidising fossil fuel burning. Any such criticism rings particularly hollow now as rich countries race to do the same thing.

Fossil fuels at COP27

US and European allies pressured developing countries at COP26 to commit to bolder action to eliminate coal power, often touting natural gas as a useful transition fuel. Now, Europe is limiting their access to alternatives by outbidding Asian and Latin American developing countries on the global LNG market while firing up their own mothballed coal-fired power stations, or extending the lifetime of operating ones.

Western leaders have also criticised China and India for buying more Russian oil and gas, financing Putin’s invasion in the process. But since the start of the war, Russia has earned €108 billion (£94 billion) in fossil fuel sales to the EU alone, accounting for over half of the country’s income from oil and gas exports.

While pipeline flows from Russia to the EU are down substantially, Russian LNG exports have actually gone up. Depressed demand for gas in China (due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions) is the saving grace that allowed Europe to fill its storage tanks ahead of winter.

One year on from the Glasgow climate pact, emissions pledges and promises have yielded to immediate security concerns. A short-term dash for gas and coal might make sense given the shock of Russia’s invasion, but ideally sky-high fossil fuel prices would speed up the transition to renewables.

Simply swapping fossil fuel dependence from one exporter to another is bad for the climate and certainly does not make energy supply more secure and affordable. Rather than an energy price crisis, the world is grappling with a fossil fuel price crisis.

The IEA expects that demand for fossil fuels will peak within five years thanks to programmes like the EU’s RePowerEU plan, the US Inflation Reduction Act and Japan’s green transformation plan, which incentivise renewables. But despite these interventions, current emission pathways predict 2.6°C of warming by 2100 – well above the objectives of the Paris agreement.

Negotiations at COP27 should be held with the full understanding that fossil fuels are not exiting the global energy mix. Developed countries must take a leading role in phasing them out to allowing developing countries to adapt a slower pace. This is the key to a fair transition away from the fuels driving climate breakdown.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Mathieu Blondeel, Research Fellow, Strategy & International Business Group, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved