By Eric Werker, Simon Fraser University | –

(The Conversation) – To justify invading Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has painted Russia as a hegemonic power re-asserting its rightful claim to imperial greatness. Yet even before the invasion, Russia’s economic capabilities were hardly capable of sustaining an empire.

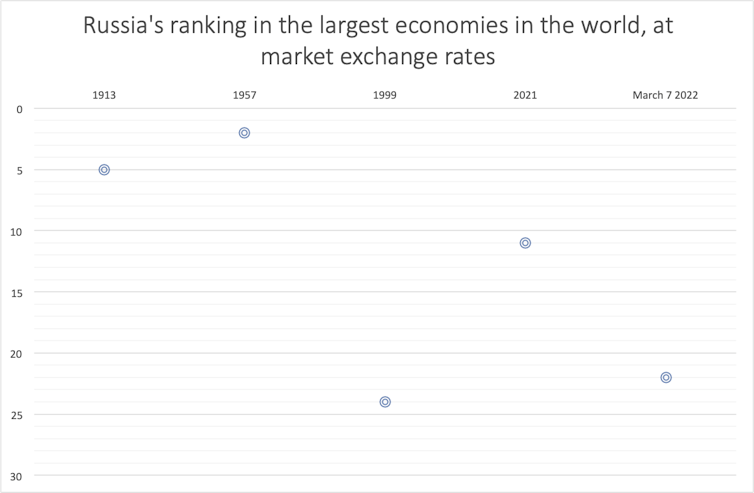

Now, with foreign sanctions presiding over a plummeting Russian ruble, Russia’s economic standing has fallen further still. If measured at today’s exchange rates, Russia’s economy would be the 22nd largest in the world, with a gross domestic product (GDP) not much larger than the state of Ohio’s.

Author provided

That’s a far cry from the past, when Russia was a true world power. According to data assembled by the late economic historian Angus Maddison, it was the fifth largest economy in the world in 1913, behind the United States, China, Germany and Britain. By 1957, when the U.S.S.R. outpaced the United States to launch the first satellite into space, the Soviet economy was the world’s second largest after America’s.

Putin’s quest for greatness

Putin was elected president following the chaotic disintegration of the Soviet Union and the 1998 financial crisis in which Russia defaulted on its debt and abandoned its fixed exchange rate.

At the time, Russia’s market-value GDP had bottomed out at US$210 billion, making it the world’s 24th largest economy, behind Austria. (All contemporary GDP figures are from the October 2021 World Economic Outlook published by the International Monetary Fund.)

Putin established an informal social contract with the Russian people based on his ability to deliver strong economic growth. Under Putin’s rule, and buoyed by a commodity price supercycle that would stretch well into the 21st century, Russia’s GDP in market exchange rates rose tenfold, returning Russia to global relevance and providing purchasing power to its middle class.

However, Russia researchers argued that as Russia’s economy began to flag, from a peak in 2013, Putin sought new legitimacy to govern through foreign policy actions to re-establish Russia’s status as a “great power.” These efforts were epitomized by the Crimean annexation of 2014.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, against the backdrop of Russia’s market-rate GDP losing a third of its value between 2013 and 2020, represents a doubling down of Putin’s strategy to seek legitimacy from “great power status,” rather than economic performance.

Yet the West’s unrelenting financial and economic sanctions have only accelerated Russia’s economic downfall.

Russian stocks traded on the U.K. market have fallen by 98 per cent, wiping out US$572 billion of wealth, while stocks on Russian exchanges remain suspended.

The Russian currency has fallen to 155 rubles per dollar — a drop of more than 50 per cent from 75 rubles per U.S. dollar before the invasion. If not for recent captial controls and the rising prices of commodities — brought about by the sanctions themselves — that make up the majority of Russia’s exports, it would fall even further.

Domino effect

A country’s market-rate GDP is its GDP converted to a global currency like the U.S. dollar. While there are other ways to measure GDP, when it comes to global trade and investment — and economic power — the market rate is what matters.

Russia’s market-rate GDP in 2021 was US$1.65 trillion, enough to make it the world’s 11th largest economy, behind South Korea. If we crudely convert Russia’s 2021 estimated GDP by March 7, 2022, currency rates, rather than the average exchange rate used last year, and place it against the 2021 market-rate GDP table, the rankings change and Russia slides to 22nd place, falling between Taiwan and Poland.

This drop is likely an underestimate. While a falling ruble lowers Russia’s exchange rate of its GDP to U.S. dollars, its weakening economy lowers its ruble GDP directly. And Russia’s isolation will erode its economic competitiveness, widening the economic gap further in the medium term.

Ukrainians confronted with the oncoming Russian army were wise to Putin’s chimeric strategy. “Don’t you have problems in your country to solve? Are you all rich there, as in the Emirates?” one elderly man heckled Russian soldiers.

Putin’s next move

Robert F. Kennedy famously observed that GDP failed to account for many things that we care about — like health and education. The fall in Russia’s market-rate GDP cannot begin to describe the human tragedy playing out in both Ukraine and Russia.

But what these figures do make clear is that Putin’s claim to legitimacy through economic performance is all but destroyed. With “great power status” tied closely to economic power, Putin’s back-door source of legitimacy from stirring up nationalist pride now seems closed as well.

Putin may have led Russia from one “Times of Troubles,” but he has delivered it to another one. That’s cold comfort to the Ukrainians, and indeed to the rest of the world, who are wondering Putin’s next move.

Eric Werker, William Saywell Professor of International Business, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image: Pixabay.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved