By Nick Engelfried | –

Climate protesters gathered at the State Capitol in Portland, Oregon in 2019 to protest the later canceled Jordan Cove LNG export terminal. (Facebook/Rogue Climate)

“The same company that’s behind the Keystone and Keystone XL pipelines now wants to use GTN Xpress to increase its transport of fracked gas into the Pacific Northwest,” said Audrey Leonard of Columbia Riverkeeper at the hearing. “We’re fighting this dangerous proposal because our climate cannot afford to lock in more fossil fuels.”

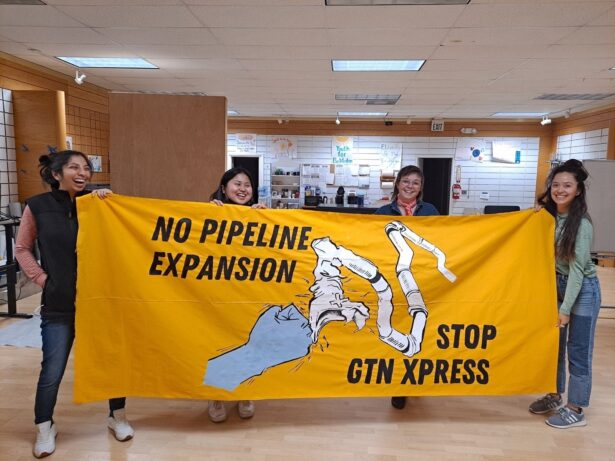

Activists and concerned members of the public assembled for the hearing at in-person locations in Phoenix, Oregon and Sandpoint, Idaho, or tuned in via Zoom to register their concerns. Comments recorded from the event will be delivered to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, which is soon expected to make a decision on whether or not GTN Xpress can move forward. The people’s hearing — convened in response to the fact that FERC has declined to hold any official public hearings on GTN in the Northwest — put a spotlight on how energy companies are trying to get around grassroots opposition to fossil fuels in the region and how activists are fighting back.

In fact, the natural gas industry’s focus on expanding the capacity of the existing GTN pipeline can in many ways be seen as a response to activists’ successful efforts to oppose new fossil fuel infrastructure in the region. Since the beginning of last decade, climate groups, Indigenous nations and their allies have defeated over 20 proposed new fossil fuel transportation projects in the Northwest, including coal and oil export terminals, natural gas pipelines and methanol plants.

The efforts of climate activists have contributed to establishing Oregon and Washington State’s reputations as places where new climate-wrecking projects will be challenged through the official permitting process, lawsuits and even with direct action. That development is one of the great climate success stories to come out of the region in recent years — however, it is now provoking a new response from industry, as companies like TC Energy shift their focus to trying to expand existing projects.

A new kind of pipeline fight

“Unlike with new pipeline projects, GTN Xpress doesn’t need many permits from state or local government,” said Maig Tinnin of Rogue Climate in Southern Oregon. “The decision on permitting is really up to FERC, which has a history of rubber-stamping fossil fuel projects. That makes this a different kind of animal from other pipeline fights we’ve been part of.”

Although GTN Xpress wouldn’t require laying any new pipe, the impacts for communities along the pipeline route would still be profound. The proposed expansion involves building a new gas compressor station in northern Oregon and upgrading existing stations in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. This would increase the volume of gas TC Energy can send through the pipeline, leading to greater potential for leaks and other accidents. In a worst-case scenario, a major gas explosion along the pipeline route could cause widespread destruction in areas ill-equipped to respond to such an emergency.

“GTN passes very near to residential areas and tourist attractions in Idaho,” said Helen Yost, an organizer with Wild Idaho Rising Tide. “In the community of Sandpoint, it goes directly under the parking lot at the base of the popular Schweitzer Ski Resort. This project is a dire threat to the Idaho tourism and recreation industries if anything goes wrong.”

Then there is the climate impact of transporting and burning so much extra gas, a process expected to result in 3.47 million metric tons of new carbon emissions per year, equivalent to adding 754,000 new cars to the roads. It is this danger to the climate, more than anything, that has galvanized opposition to GTN Xpress — not only from grassroots organizations but from top elected officials in a region that is doing more than almost any in the country to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels.

A region transitioning to renewables

“All along the pipeline route, our Northwest communities are already seeing the impacts of climate change,” Tinnin said. “The climate crisis is here now, and we’re trying to make the changes needed to prevent it from getting worse. GTN Xpress would undermine those efforts.”

Tinnin was inspired to get involved in climate organizing after devastating wildfires swept through Southern Oregon in 2020, destroying more than 2,300 homes and forcing tens of thousands of people to evacuate. In addition to longer, more intense fire seasons, the Northwest has suffered in recent years from record-smashing heat waves and reduced snowpack that contributes to lower water flow in streams used by salmon. For over a decade, activists have fought back by working to stop new fossil fuel projects and close existing coal-fired power plants. More recently, these efforts have been bolstered by a raft of groundbreaking climate policies enacted by state and local government decision makers.

In 2019, Washington’s legislature passed what was at the time one of the strongest renewable energy laws in the country, mandating electric utilities source 100 percent of their energy from carbon-free sources by 2045. In 2021, Oregon passed its own, even more ambitious law requiring all renewable electricity by 2040. Both states have taken a variety of other steps to curb their carbon emissions, including incentives for home renewable energy installations, efficiency standards for buildings and appliances and regulations to encourage the shift to electric vehicles.

Last November, the Washington State Building Code Council passed one of the nation’s strictest regulations to prevent natural gas hookups in new residential buildings, a move coming on the heels of similar standards for commercial structures. If implemented as planned, these policies will result in dramatically reduced demand for fossil fuels, including natural gas, over the next couple of decades.

Oregon and Washington policymakers’ push for renewable energy also aligns with the goals of many Indigenous governments. For example, the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission has announced its own vision for a renewable energy future in the region and opposes the GTN expansion. “This project threatens our way of life,” said Alysia Aguilar Littleleaf of Littleleaf Guides, an Indigenous-owned flyfishing guiding business on the Warm Spring Reservation. “Our guide service allows us to continue living off the land and sustain ourselves as Indigenous tribal members. GTN Xpress puts that in danger.”

Such concerns have prompted high-ranking elected officials to raise objections to the pipeline expansion. Last summer, the state attorneys general of Oregon, Washington and California filed a motion requesting FERC deny GTN Express’ permit, arguing the project’s draft environmental impact statement fails to adequately consider climate impacts and a lack of public need for the project. Both of Oregon’s U.S. senators, Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden, also oppose GTN Xpress.

Yet, despite such wide-ranging opposition, the fate of efforts to stop the pipeline expansion remains unclear. This underscores the difficulties involved for grassroots organizations seeking to pressure a remote federal agency with little built-in accountability to the broader public.

Growing the fossil fuel resistance

“There are challenges involved in grassroots organizations in the Northwest trying to interact meaningfully with federal agencies based on the other side of the country,” said Yost of Wild Idaho Rising Tide. “Still, we believe FERC has a responsibility to consider whether the GTN expansion and its global impacts are truly in the public interest.”

The controversy over GTN is not the first time Northwest climate activists have struggled to influence FERC, an agency many climate groups say is beholden to fossil fuel interests. In 2020, the agency approved the Jordan Cove LNG export terminal in Southern Oregon, which climate groups had been fighting for more than a decade. In a major climate victory, Jordan Cove’s developer later withdrew its permit application after failing to obtain key approvals from Oregon state agencies. However, the fact that states have little authority to stop GTN’s expansion gives climate groups and their allies more limited options for stopping the project.

Even so, FERC’s soon-to-be-announced decision on GTN Xpress is unlikely to be the last word on the project, regardless of the outcome. “Thousands of people have already weighed in to FERC by signing petitions, submitting comments and calling on the agency to do its job by listening to Northwest communities,” said Dan Serres of Columbia Riverkeeper, an organization that has played a key role in the regional fossil fuel resistance. “All along the pipeline route we’re raising the alarm about GTN Xpress, and we’re not going to stop.”

Exactly what the next stage of the resistance to GTN Xpress looks like remains to be seen. However, developers of other major fossil fuel projects in the Pacific Northwest have been met with large protests and even civil disobedience. Climate groups can also petition FERC for a rehearing or challenge the pipeline expansion in court, which would further delay work on the project and allow additional time for organizing.

“At a time when our region is moving away from fossil fuels, the gas industry is trying to push its stranded industry on the Northwest with GTN Xpress,” Yost said. “If FERC rubber stamps this project, we’ll keep fighting it.”

Correction 2/18/2023: Audrey Leonard is with Columbia Riverkeeper, not Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Nick Engelfried is an environmental writer, educator, and activist living in the Pacific Northwest. He is the author of Movement Makers: How Young Activists Upended the Politics of Climate Change.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved