By Erdağ Göknar | –

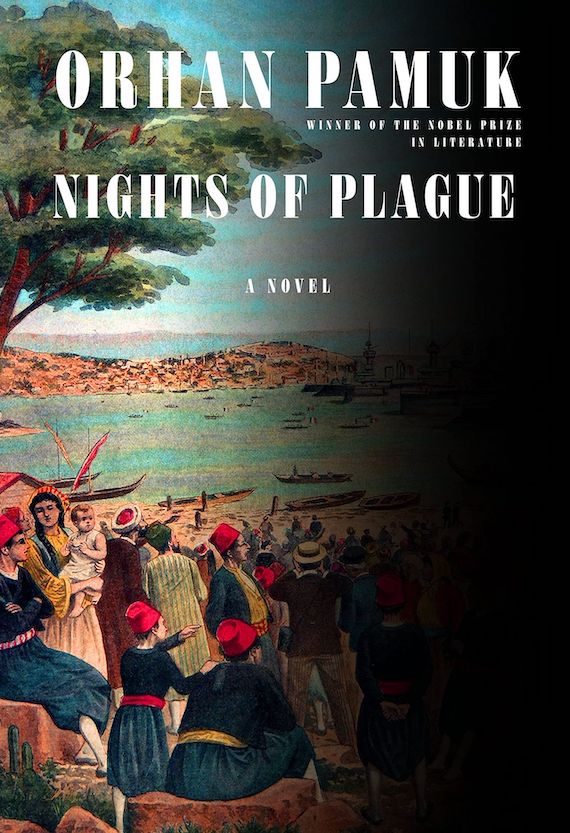

( LA Review of Books) – DURING THE LONG summer days in Istanbul, Orhan Pamuk devotes himself to intensive writing on Büyükada, an island in the Sea of Marmara, and in the evenings, he meets with visitors. Last August, Pamuk and I had dinner there and discussed everything from politics (could Erdoğan survive the May 2023 elections?) to the author’s illustrated notebooks, selections from which were recently published in Turkish and French. (The English version, Memories of Distant Mountains, won’t appear for another year or two.) His latest novel Nights of Plague (2022) was soon to be released in the United States in English translation, but Pamuk had already started on his next novel, with the working title The Card Players — yes, he was familiar with the eponymous five-painting Cézanne series.

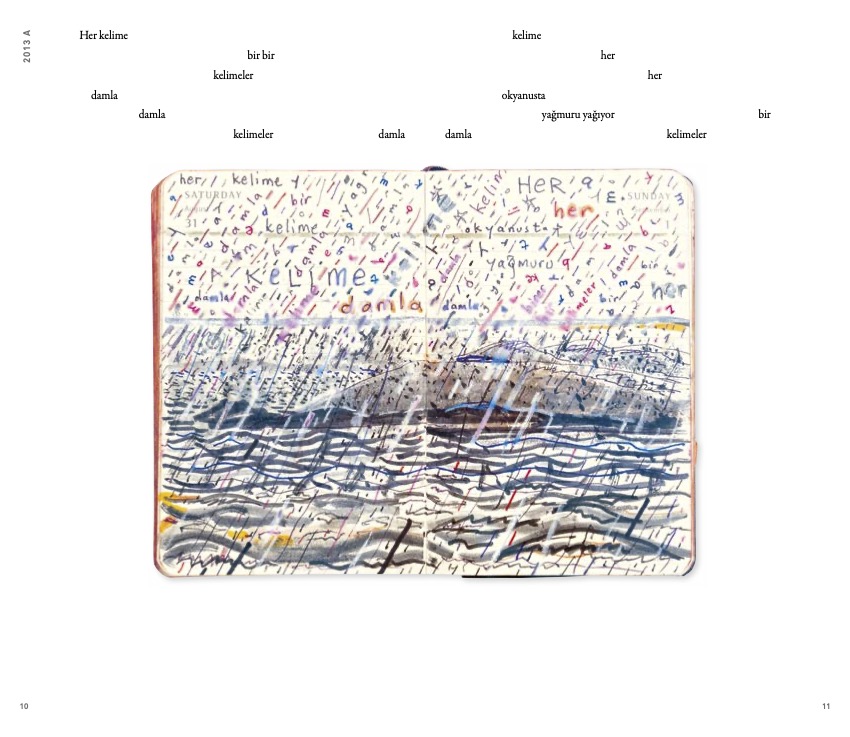

As we talked, Pamuk placed a sheaf of colorful manuscript pages before me. In the first illustration, words and letters were raining down from the sky in an arresting manner.

That word-storm set the volume’s tone, a series of miniature illustrations and notes serving to illuminate Pamuk’s writing process. They offer windows onto his creative method as a self-described “visual writer” who often writes through a dialectic of image and text. This might take the form of ekphrasis, as in My Name Is Red (2001), which is punctuated with descriptive prose depicting Islamic miniatures; or it might simply be the basis for developing the novels — that is, figures, scenes, or settings sketched out as he wrote. Accompanying text might appear as a separate caption, as an image itself (cobblestones, for example), or as an embellishment to an existing image. He was, more or less, painting with words. Later, we agreed to discuss Nights of Plague and some of these notebook illustrations in a public event at Duke University, where I regularly taught a Pamuk seminar.

Three months later, as we drove to the campus from the airport, Pamuk spoke quickly, in the manner of one whose mind races ahead of his words. This would be the first time he had discussed the illustrations. He was also in the midst of teaching a seminar on “The Political Novel” at Columbia University, where he taught each fall. On the reading list was his own novel Snow (2002), and he told me that situating his own books was part of his work as a writer. As he spoke, it seemed as if ideas and information were swirling around us like the words in his illustration. Occasionally, he turned toward me and widened his eyes for emphasis. “Which images are we going to discuss?” he asked.

It was a chilly November day, but he cracked the window as a precaution. As we drove, he continued to describe his writer’s life in New York and on the road. We discussed his schedule on campus, where he would be giving two talks: the first on Nights of Plague and the second on the notebooks he’d been keeping for the last 14 years. Pamuk’s creative life had proliferated, and, in addition to being a global author, he’d become a curator, a photographer, and an artist — something he’d aspired to be as a young man. Moreover, illustrations, including sketches of character types, informed his writing process as a kind of scaffolding. For Nights of Plague, for example, he’d sketched figures like a fez-clad quarantine official whose duty was to disinfect areas with a special Lysol spray pump: it was a succinct portrait of late Ottoman modernity.

When we got to the hotel, we set to work going over the draft of a collection of 30 interviews that I was co-editing with Pelin Kıvrak, covering Pamuk’s four decades as a published author. I pointed him to the last piece, an interview about interviews we had planned but not yet completed. He looked at the questions and immediately began to take notes. He described various aspects of the interview as a literary vehicle and as an alternative literary history. He had, in his youth, studied journalism. Interviews, whether investigative or ethnographic, had become a part of his writing process and sometimes entered his plots themselves. Ka, the protagonist of Snow, posed as a reporter and often asked questions of those he met in the small Anatolian border town where the novel is set. In A Strangeness in My Mind (2015), interviews of Istanbul migrants and street hawkers formed part of his quasi-ethnographic process. Pamuk talked about the place of the interview in the writerly life, about paratexts that situate the author or the book, and about a writer’s consideration of different local and international audiences. “I love to talk about my novels,” he said. “Doing interviews is a sort of a public introduction to the reception of the book and also the possibility of manipulating it.”

Once we had finished, we walked to Duke’s East Campus. While we waited for the event to begin, I skimmed the notes for my introduction describing Pamuk’s significance as a practitioner of the global novel. Most of his work is set in Istanbul, the former capital of the Ottoman Empire and the city of his birth. Writing with a focus on Turkish culture, history, and politics, he mixes multiple genres, from the historical novel to the romance and detective story, from the political novel to the autobiography. Along with allusions to Turkish and world literature, common tropes in Pamuk’s work include identity, conspiracy, doubles, obsessive love, murder mystery, coups, curation, Sufism, and the power of the state.

For Pamuk, the novel is method, a multifaceted process of archival work, interviews, reading in the genre, and locating visual corollaries or memorial objects. He brings to his fiction a historian’s attention to detail. It’s not surprising that the narrator of Nights of Plague, Mina Mingher, is a historian and scholar who assembles the story from an “archive” of letters written by an Ottoman sultan’s niece. Pamuk’s fiction occupies the gray area between history and literature — or, as Mina states, between “a historical novel and a history written in the form of a novel.” His work often reflects the novelist as archivist and curator, perhaps best exemplified in the Museum of Innocence project that began in 2008 with the novel of that same title and then became an actual brick-and-mortar museum in Istanbul in 2012 and later, in 2015, a documentary film. Taken all together, the project reflects Pamuk’s work with radical intertextuality of object, image, and narrative.

Nights of Plague is an outbreak narrative, set during a contagion in the late Ottoman era. What is known historically as the “third major plague pandemic,” which began in China in 1855, has already killed millions before it arrives, in 1901, to Mingheria, a half-Muslim, half-Christian island in the Ottoman Mediterranean (with evocations of Cyprus and Crete, as well as Pamuk’s summer haunt of Büyükada). Sultan Abdul Hamid II (who reigned 1876–1909) sends his most accomplished quarantine expert, Bonkowski Pasha (something of an early-20th-century Anthony Fauci), to the island. Some of the Muslims, including followers of a Sufi religious sect and its leader Sheikh Hamdullah, refuse to respect the quarantine. In the context of state-backed quarantine measures, Nights of Plague also tells a story of political formation and national self-determination, tracing the rise of one Kâmil Pasha as founding president of the independent island-nation of Mingheria, soon to be freed from Ottoman rule and embark on its own quirky cultural revolution reminiscent of Turkey’s own post-Ottoman modernization.

In the novel, physical manifestations of the plague combine with allegory, as colonial modernity confronts Islamic tradition. The Ottoman state’s liminal position is captured by the fact that Abdul Hamid is both an autocrat and a modernizer — an avid reader of Sherlock Holmes and a fan of his deductive reasoning. This depiction is based on historical fact; indeed, Yervant Odyan, an Ottoman Armenian writer, even wrote a novel about the sultan’s fondness for the work of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle entitled Abdülhamid and Sherlock Holmes (1911). This novel is a literary curiosity today, but at the time of its publication, it offered a denigrating portrait of the deposed sultan after the Second Constitutional Young Turk Revolution of 1908. By contrast, Nights of Plague is a nuanced take on Abdul Hamid’s end-of-empire legacy.

Pamuk has nurtured an interest in the nexus linking plagues, quarantines, religion, and state formation for almost 40 years. In Pamuk’s second novel, Silent House (1983, in Turkish), another historian, Faruk Darvınoğlu, researches the “plague state” created when a contagion ravages the Ottoman Empire and the government goes into remote quarantine. The theme reappears in Pamuk’s third novel, The White Castle (1985), set in the 17th century, in which a plague epidemic becomes a metaphor for conversion for a Venetian man captured and enslaved by the Ottomans. Working with his Muslim master, he is able to predict the end of the plague by tracking the number of deaths in each neighborhood. Methodical thought uneasily confronts Muslim fatalism here, as it does in Nights of Plague, in which the epidemic becomes a catalyst for a new political formation.

Among other accomplishments, Nights of Plague places the reader at the intersection of epidemiology and nation-state formation. As such, it dramatizes a variety of biopolitics. If we can speak of the nation as an “imagined community” (in Benedict Anderson’s formulation), then we can also consider its “imagined immunities,” Priscilla Wald argues in her 2008 book Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative. “While emerging infections are inextricable from global interdependence in all versions of these [outbreak] accounts,” she writes, “the threat they pose requires a national response. The community to be protected is thereby configured in cultural and political as well as biological terms: the nation as immunological ecosystem.” Readers understand, morbidly, that the modern state “inoculates” against political others who are relegated to a lethal precarity.

In Nights of Plague, Pamuk confronts us with the ironic idea that a political entity, even a nation-state, could arise in response to, or as a symptom of, an epidemic.

During the event, Pamuk further elaborated on this topic, contrasting novels in which plagues figure as documented material events, as in Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), with those in which they function as allegories, such as Albert Camus’s The Plague (1947). In Pamuk’s novel, it is a little of both. Of course, the plague in the novel isn’t just a plague — it’s a force of historical transformation like religion, modernity, or colonialism. The presence of the contagion turns people into others, transforms them forever; it demands, at a minimum, some degree of conversion to the rules and regulations of modern governmentality, something we’ve all experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nights of Plague speaks back to the Orientalist tropes of the European plague novel, showing how the imposition of quarantine in any context (not just Islamic) comes with potential political or epistemic violence (including disinformation). In a 2020 New York Times editorial entitled “What the Great Pandemic Novels Teach Us,” Pamuk summarized the basis of mob anger at quarantine regulations as a widespread but mistaken belief that “[t]he disease is foreign, it comes from outside, it is brought in with malicious intent.”

For his second talk, in the auditorium of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke, Pamuk explained the writerly process that rests at the intersection of image and text. The pages of Pamuk’s notebooks contain a running commentary on the labors of writing, as well as intimacies, confessions, and symbolic or poetic codes. They not only trace his travels in Istanbul, Urbino, Mumbai, Goa, Granada, Venice, New York, Paris, Los Angeles, and elsewhere, but also reveal what might be called the topographies of the writer’s mind. A piece of gossip sits next to an epiphany. A statement of nostalgia shares the page with news of publications or a simple accounting of the day’s expenses. That contrast, in which the profound cohabits with the quotidian, reveals the writer in the messiness of life. Pamuk’s notebooks are the calm eye of a storm of creativity. They are itinerary and raw thought, both meditative and marginal. For anyone interested in the inner workings of a brilliant mind, the notebooks are an addicting pleasure that lay bare the wellsprings of Pamuk’s writing.

The images contained in his notebooks, which were projected on a large screen during the event, reveal ideas, visions, daily concerns, and snippets of conversation intertwined with vistas and landscapes. At times, the words actually constitute the “view.” As Pamuk writes, “There was a time when words and pictures were one. There was a time, words were pictures and pictures were words.”

The images Pamuk projected included the picture of words raining down from the sky, as well as vistas of Crete. One illustration contained the line, “Everything begins with a VIEW.” We saw drawings (based on historical photographs) of fez-wearing late-Ottoman youths fishing with nets, which uncovered Pamuk’s fascination with narrative detail and local color. And we saw an illustration that captured the Italian skyline of Urbino, which inspired the city of Arkaz in Nights of Plague, showing how the author’s travel and writing are linked. The image had a kind of aphorism at the top that read, “Me at one time in the past: fable and history; writing and picture.”

In response to a question from the audience, Pamuk discussed ekphrasis, the process of painting with words. An eager student asked which takes precedence, image or text? “It’s not translating that image,” he responded. “It’s putting that image in words, describing that image with words … When we think, do we use pictures or words or neither? Or is some chemistry happening? What is a thought, is it an image? Sometimes it’s an image. Sometimes it’s a word. When I call myself a visual writer, for me, a thought is closer to an image.” As he responded to questions, Pamuk frequently made the audience weigh and consider — and laugh. At one point, he produced the current notebook he carried with him as his portable studio, in which he sketched and wrote whenever time allowed. The attentive faces of the spectators revealed that he was connecting, in word and image, with a new generation of Pamuk readers.

Reprinted from The Los Angeles Review of Books with the author’s permission.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved