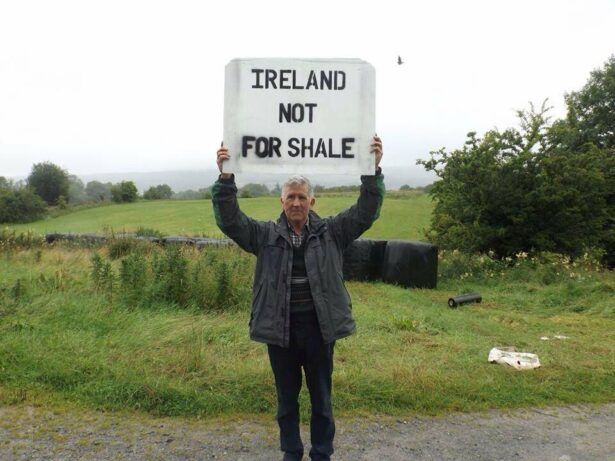

Anti-fracking activists celebrate Ireland’s ban. (LL/Dervilla Keegan)

In Australia, unconventional fossil gas exploration has been on the rise over the last two decades. Coal seam gas wells have been in production since 2013, while community resistance has so far prevented the threat of shale gas fracking. The climate crisis and state commitments under the Paris Agreement means that the window for exploration is closing. But the Australian economy remains hooked on fossil fuels and the industry claims that fossil gas is essential for economic recovery from COVID, “green growth” and meeting net-zero targets.

The Northern Territory, or NT, government is particularly eager to exploit its fossil fuel reserves and wants to open up extraction in the Beetaloo Basin as part of its gas strategy. The NT recently announced a $1.32 billion fossil fuel subsidy for gas infrastructure project Middle Arm and greenlighted the drilling of 12 wells by fracking company Tamboran Resources as a first step towards full production.

Gas exploration is inherently speculative with high risks. The threat of reputational damage is high enough that large blue chip energy companies like Origin Energy — a major player in the Australian energy market — are turning away from shale. This leaves the field to smaller players who are willing to take a gamble in search of a quick buck. This is precisely how Tamboran came to prominence in Australia. After buying out Origin Energy in September 2022, Tamboran is now the biggest player in the Northern Territory’s drive to drill.

NT anti-fracking campaigner Hannah Ekin described this point as “a really key moment in the campaign to stop fracking in the Beetaloo basin.” For over a decade, “Traditional Owners, pastoralists and the broader community have held the industry at bay, but we are now staring down the possibility of full production licenses being issued in the near future.”

Despite this threat, Tamboran has been stopped before. In 2017, community activists in Ireland mobilized a grassroots movement that forced the state to revoke Tamboran’s license and ban fracking. Although the context may be different, this successful Irish campaign has many key insights to offer those on the frontlines of resistance in Australia — as well as the wider anti-extraction movements all over the world.

Tamboran comes to Ireland

In February 2011, Tamboran was awarded an exploratory license in Ireland — without public knowledge or consent. They planned to exploit the shale gas of the northwest carboniferous basin and set their sights on county Leitrim. The county is a beautiful, mountainous place, with small communities nestled in valleys carved by glaciers in the last ice age. The landscape is watery: peat bogs, marshes and gushing rivers are replenished by near daily downpours as Atlantic coast weather fronts meet Ireland’s western seaboard. Farming families go back generations on land that can be difficult to cultivate. Out of this land spring vibrant and creative communities, despite — or perhaps because of — the challenges of being on the margins and politically peripheral.

The affected communities first realized Tamboran’s plans when the company began a PR exercise touting jobs and economic development. In seeking to understand what they faced, people turned to other communities experiencing similar issues. A mobile cinema toured the glens of Leitrim showing Josh Fox’s documentary “Gasland.” After the film there were Q&As with folks from another Irish community, those resisting a Shell pipeline and gas refinery project at Rossport. Out of these early exchanges, the grassroots community response Love Leitrim, or LL, formed in late 2011.

Resisting fracking by celebrating the positives about Leitrim life was a conscious strategic decision and became the group’s hallmark. In LL’s constitution, campaigners asserted that Leitrim is “a vibrant, creative, inclusive and diverse community,” challenging the underlying assumptions of the fracking project that Leitrim was a marginal place worth sacrificing for gas. The group developed a twin strategy of local organizing — which rooted them in the community — and political campaigning, which enabled them to reach from the margins to the center of Irish politics. This combination of “rooting” and “reaching” was crucial to the campaign’s success.

5 key rooting strategies

The first step towards defeating Tamboran in Ireland was building a movement rooted in the local community. Out of this experience, five key “rooting strategies” for local organizing emerged — showing how the resistance developed a strong social license and built community power.

1. Build from and on relationships. Good relationships were essential to building trust in LL’s campaign. Who was involved — and who was seen to be involved — were crucial for rooting the campaign in the community. Local people were far more likely to trust and accept information that was provided by those they knew, and getting the public support of local farmers, fishers and well-known people was crucial. Building on existing relationships and social bonds, LL became deeply rooted in local life in a way that provided a powerful social license and a strongly-rooted base to enable resistance to fracking.

2. Foster ‘two-way’ community engagement. LL engaged the community with its campaign and, at the same time, actively participated as volunteers in community events. This two-way community engagement built trust and networked the campaign in the community. LL actively participated in local events such as markets, fairs and the St. Patrick’s Day parade, which offered creative ways to boost their visibility. At the same time, LL also volunteered to support events run by other community groups, from fun-runs to bake sales. According to LL member Heather (who, along with others in this article, is quoted on the condition of anonymity), this strategy was essential to “building up trust … between the group, its name and what it wants, and the community.”

3. Celebrate community. In line with its vision, LL celebrated and fostered community in many ways. This was typified by its organizing of a street feast world café event during a 2017 community festival that saw people come together over a meal to discuss their visions of Leitrim now and for their children. LL members also supported local renewable energy and ecotourism projects that advanced alternative visions of development. Celebrating and strengthening the community in this way challenged the fundamental assumptions of the fracking project — a politics of disposability which assumed that Leitrim could be sacrificed to fuel the extractivist economy.

4. Connect to culture. Campaigners saw culture as a medium for catalyzing conversations and connecting with popular folk wisdom. LL worked with musicians, artists and local celebrities in order to relate fracking to popular cultural and historical narratives that resonated with communities through folk music and cultural events. This was particularly important in 2016, the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising, which ultimately led to Irish independence from the British Empire. Making those connections tapped into radical strands of the popular imagination. Drawing on critical counter-narratives in creative ways overcame the potential for falling into negative activist stereotypes. Through culture, campaigners could present new or alternative stories, experiences or ideas in a way that evocatively connected with people.

5. Build networks of solidarity. Reaching out to other frontline communities was a powerful and evocative way to raise awareness of fracking and extractivism from people who had experienced them first-hand. As local campaigner Bernie explained, “When someone comes, it’s on a human level people can appreciate and understand. When they tell their personal story, that makes a difference.”

Perhaps the most significant guest speaker was Canadian activist Jessica Ernst, whose February 2012 presentation to a packed meeting in the Rainbow ballroom was described by many campaigners as a key moment in the campaign. Ernst is a former gas industry engineer who found herself battling the fracking industry on her own land. She told her personal story, the power of which was heightened by her own industry insider credentials and social capital as a landowner. Reflecting on the event, LL member Triona remembered looking around the room and seeing “all the farmers, the landowners, who are the important people to have there — and people were really listening.”

4 key reaching strategies

With a strong social license and empowered network of activists, the next step for the anti-fracking movement was to identify how to make their voices heard and influence public policy. This required reaching beyond the local community scale to engage in national political decision making around fracking. Four key strategies enabled campaigners to successfully jump scales and secure a national fracking ban.

1. Find strategic framings. Tamboran sought to frame the public conversation on narrow technical issues surrounding single drilling sites, pipelines and infrastructure, obscuring the full impact of the thousands of planned wells. As LL campaigner Robert pointed out, this “project-splitting” approach “isn’t safe for communities, but it’s easier for the industry because they’re getting into a position where they’re unstoppable.” Addressing the impact of the entire project at a policy level became a key concern for campaigners. LL needed framings that would carry weight with decision makers, regulators and the media. Listening and dialogue in communities helped campaigners to understand and root the campaign in local concerns. From this, public health and democracy emerged as frames that resonated locally, while also carrying currency nationally.

The public health frame mobilized a wide base of opposition. Yet it was not a consideration in the initial Irish Environmental Protection Agency research to devise a regulatory framework for fracking. LL mobilized a campaign that established public health as a key test of the public’s trust in the study’s legitimacy. The EPA conceded and amended the study’s terms of reference to include public health. This enabled campaigners to draw on emerging health impact research from North American fracking sites, providing evidence that would have “cache with the politicians,” as LL member Alison put it. Working alongside campaigners from New York, LL established the advocacy group Concerned Health Professionals of Ireland, or CHPI, mirroring a similar, highly effective New York group. CHPI was crucial to highlighting the public health case for a ban on fracking and shaping the media and political debate.

2. Demonstrate resistance. Having rooted the campaign in local community life, LL catalyzed key groups like farmers and fishers to mobilize their bases. Farmers in LL worked within their social networks to organize a tractorcade. “It was all word of mouth … knocking on doors and phone calls,” said Fergus, the lead organizer for the event. Such demonstrations were “a show of solidarity with the farmers who are the landowners,” Triona recalled. They were also aimed at forcing the farmer’s union to take a public position on fracking. The event demonstrated to local farmers union leaders that their members were opposed to fracking, encouraging them to break their silence on the issue.

Collective action also enforced a bottom line of resistance to the industry. Tamboran made one attempt to drill a test well in 2014. Community mobilization prevented equipment getting to the site for a week while a legal battle over a lack of an environmental impact assessment was fought and won. Reflecting on this success, Robert suggested that communities can be nodes of resistance to “fundamental, large problems that aren’t that easy to solve” because “one of the things small communities can do is simply say no.” And when frontline communities are networked, then “every time a community resists, it empowers another community to resist.”

3. Engage politicians before regulators. In 2013, when Tamboran was renewing its license, campaigners found that there was no public consultation mechanism. Despite this, LL organized an “Application Not to Frack.” This was printed in a local newspaper, and the public was encouraged to cut it out and sign it. This grassroots counter-application carried no weight with regulators, but with an emphasis on rights and democracy, it sent a strong signal to politicians.

Submitting their counter application, LL issued a press release: “Throughout this process people have been forgotten about. We want to put people back into the center of decision making … We are asking the Irish government: Are you with your people or not?” At a time when public sentiment was disillusioned with the political establishment in the aftermath of the 2011 financial crisis, LL tapped into this sentiment to discursively jump from the scale of a localized place-based struggle to one that was emblematic of wider democratic discontents and of national importance.

Frontline environmental justice campaigns often experience procedural injustices when navigating governance structures that privilege scientific/technical expertise. Rather than attempt an asymmetrical engagement with regulators, LL forced public debate in the political arena. In that space, they were electors holding politicians to account rather than lay-people with insufficient scientific knowledge to contribute to the policy making process. The group used a variety of creative tactics and strategic advocacy to engage local politicians. This approach — backed up by a strongly rooted base — led to unanimous support for a ban from politicians in the license area. In the 2016 election, the only pro-fracking candidate failed to win a seat. Local democratic will was clear. Campaigners set their sights on parliament and a national fracking ban.

4. Focus on the parliament. The lack of any public consultation before exploration commenced led campaigners to fear that decisions would continue to be made without public scrutiny. LL built strategic relationships with politicians across the political spectrum with the aim of forcing accountability in the regulatory system. A major obstacle to legislation was the ongoing EPA study, which was to inform government decisions on future licensing. But it emerged that CDM Smith, a vocally pro-fracking engineering firm, had been contracted for much of the work. The study was likely to set a roadmap to frack.

Campaigners had two tasks: to politically discredit the EPA study and work towards a fracking ban. They identified the different roles politicians across the political spectrum — and between government and opposition — could strategically play in the parliamentary process. While continuing a public campaign, the group engaged in intensive advocacy efforts, working with supportive parliamentarians to host briefings where community members addressed lawmakers, submitted parliamentary questions to the minister, used their party’s speaking time to address the issue, raised issues at parliamentary committee hearings, and proposed motions and legislative bills.

While the politicians were also not environmental experts, their position as elected representatives meant that regulators were accountable to them. Political pressure thus led to the shelving of the compromised EPA study and paved the way for a ban. Several bills had been tabled. By chance, the one that was first scheduled for debate was from a Leitrim politician whose bill was backed by campaigners as the most watertight. With one final push from campaigners, it secured support from lawmakers across parties and a government motion to block it was fought off. In November 2017, six years after Tamboran arrived in Leitrim, fracking was finally banned in Ireland. It was a win for people power and democracy.

Building a bridge to the Beetaloo and beyond

Pacifist-anarchist folk singer Utah Phillips described folk songs as “bridges” between past struggles and the listener’s present. Bridges enable the sharing of knowledge and critical understanding across time and distances. Similarly, stories of struggle act as a bridge, between the world of the reader and the world of the story, sharing wisdom, and practical and ethical knowledge. The story of successful Irish resistance to Tamboran is grounded in a particular political moment and a particular cultural context. The political and cultural context faced by Australian campaigners is very different. Yet there are certainly insights that can bridge the gap between Ireland and Australia.

The Irish campaign shows us how crucial relationships and strongly rooted community networks can be when people mobilize. In the NT, campaigners have similarly sought to build alliances across the territory and between traditional Indigenous owners and pastoralists. This is crucial, suggests NT anti-fracking campaigner Hannah Ekin, because “the population affected by fracking in the NT is very diverse, and different communities often have conflicting interests, values and lifestyles.”

LL’s campaign demonstrates the importance of campaign framings reflective of local contexts and concerns. While public health was a unifying frame in Ireland, Ekin notes that the protection of water has become “a real motivator” and a rallying cry that “unites people across the region” because “if we over-extract or contaminate the groundwater we rely on, we are jeopardizing our capacity to continue living here.”

The Beetaloo is a sacred site for First Nations communities, with sacred song lines connected to the waterways. “We have to maintain the health of the waterways,” stressed Mudburra elder Raymond Dimikarri Dixon. “That water is alive through the song line. If that water isn’t there the songlines will die too.”

In scaling up from local organizing to national campaigning, the Irish campaign demonstrated the importance of challenging project splitting and engaging the political system to avoid being silenced by the technicalities of the regulatory process. In the NT, the government is advancing the infrastructure to drill, transport and process fracked gas. This onslaught puts enormous pressure on campaigners. “It’s death by a thousand cuts,” Ekin noted. “We are constantly on the back foot trying to stop each individual application for a few wells here, a few wells there, as the industry entrenches itself as inevitable.”

In December 2022, Environment Minister Lauren Moss approved a plan by Tamboran Resources to frack 12 wells in the Beetaloo as they move towards full production. But campaigners are determined to stop them: the Central Australian Frack Free Alliance, or CAFFA, is taking the minister to court for failing to address the cumulative impacts of the project as a whole. By launching this case CAFFA wants to shift the conversation to the bigger issue of challenging a full scale fracking industry in the NT. As Ekin explained, “We want to make the government listen to the community, who for over a decade now have been saying that fracking is not safe, not trusted, not wanted in the territory.”

Hannah Ekin of the Central Australian Frack Free Alliance and Love Leitrim contributed to this article.

Correction 3/3/2023: An earlier version of this story misspelled Hannah Ekin’s last name as Mekin.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved