By Matthew Savoca, Stanford University | –

As a conservation biologist who studies plastic ingestion by marine wildlife, I can count on the same question whenever I present research: “How does plastic affect the animals that eat it?”

This is one of the biggest questions in this field, and the verdict is still out. However, a recent study from the Adrift Lab, a group of Australian and international scientists who study plastic pollution, adds to a growing body of evidence that ingesting plastic debris has discernible chronic effects on the animals that consume it. This work represents a crucial step: moving from knowing that plastic is everywhere to diagnosing its effects once ingested.

Patrick Kavanagh/Wikipedia, CC BY

From individual to species-level effects

There’s wide agreement that the world is facing a plastic pollution crisis. This deluge of long-lived debris has generated gruesome photos of dead seabirds and whales with their stomachs full of plastic.

But while consuming plastic likely killed these individual animals, deaths directly attributable to plastic ingestion have not yet been shown to cause population-level effects on species – that is, declines in population numbers over time that are linked to chronic health effects from a specific pollutant.

MBARI: “Microplastics in the ocean: A deep dive on plastic pollution in Monterey Bay”

One well-known example of a pollutant with dramatic population effects is the insecticide DDT, which was widely used across North America in the 1950s and 1960s. DDT built up in the environment, including in fish that eagles, osprey and other birds consumed. It caused the birds to lay eggs with shells so thin that they often broke in the nest.

DDT exposure led to dramatic population declines among bald eagles, ospreys and other raptors across the U.S. They gradually began to recover after the Environmental Protection Agency banned most uses of DDT in 1972.

Ingesting plastic can harm wildlife without causing death via starvation or intestinal blockage. But subtler, sublethal effects, like those described above for DDT, could be much farther-reaching.

Numerous laboratory studies, some dating back a decade, have demonstrated chronic effects on invertebrates, mammals, birds and fish from ingesting plastic. They include changes in behavior, loss of body weight and condition, reduced feeding rates, decreased ability to produce offspring, chemical imbalances in organisms’ bodies and changes in gene expression, to name a few.

However, laboratory studies are often poor representations of reality. Documenting often-invisible, sublethal effects in wild animals that are definitively linked to plastic itself has remained elusive. For example, in 2022, colleagues and I published a study that found that some baleen whales ingest millions of microplastics per day when feeding, but we have not yet uncovered any effects on the whales’ health.

Scarring seabirds’ digestive tracts

The Adrift Lab’s research focuses on the elegant flesh-footed shearwater (Ardenna carneipes), a medium-size seabird with dark feathers and a powerful hooked bill. The lab studied shearwaters nesting on Lord Howe Island, a tiny speck of land 6 miles long by one mile wide (16 square kilometers) in the Tasman Sea east of Australia.

This region has only moderate levels of floating plastic pollution. But shearwaters, as well as petrels and albatrosses, are part of a class known as tube-nosed seabirds, with tubular nostrils and an excellent senses of smell. As I have found in my own research, tube-nosed seabirds are highly skilled at seeking out plastic debris, which may smell like a good place to find food because of algae that coats it in the water. Indeed, the flesh-footed shearwater has one of the highest plastic ingestion rates of any species yet studied.

Marine ecologist Jennifer Lavers, head of the Adrift Lab, has been studying plastic debris consumption in this wild shearwater population for over a decade. In 2014 the lab began publishing research linking ingested plastic to sublethal health effects.

Yamashita et al., 2021, CC BY-ND

In 2019, Lavers led a study that described correlations between ingested plastic and various aspects of blood chemistry. Birds that ingested more plastic had lower blood calcium levels, along with higher levels of cholesterol and uric acid.

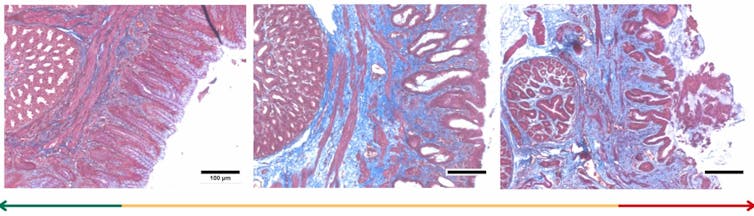

In January 2023, Lavers’ group published a paper that found multiorgan damage in these shearwaters from ingesting both microplastic fragments, measuring less than a quarter inch (five millimeters) across, and larger macroplastic particles. These findings included the first description of overproduction of scar tissue in the birds’ proventriculus – the part of their stomach where chemical digestion occurs.

This process, known as fibrosis, is a sign that the body is responding to injury or damage. In humans, fibrosis is found in the lungs of longtime smokers and people with repeated, prolonged exposure to asbestos. It also is seen in the livers of heavy drinkers. A buildup of excessive scar tissue leads to reduced organ function, and may allow diseases to enter the body via the damaged organs.

A new age of plastic disease

The Adrift Lab’s newest paper takes these findings still further. The researchers found a positive relationship between the amount of plastic in the proventriculus and the degree of scarring. They concluded that ingested plastic was causing the scarring, a phenomenon they call “plasticosis.”

Many species of birds purposefully consume small stones and grit, which collect in their gizzards – the second part of their stomachs – and help the birds digest their food by pulverizing it. Critically, however, this grit, which is sometimes called pumice, is not associated with fibrosis.

Charlton-Howard et al., 2023, CC BY

Scientists have observed associations between plastic ingestion and pathogenic illness in fish. Plasticosis may help explain how pathogens find their way into the body via a lacerated digestive tract.

Seabirds were the first sentinels of possible risks to marine life from plastics: A 1969 study described examining young Laysan albatrosses (Phoebastria immutabilis) that had died in Hawaii and finding plastic in their stomachs. So perhaps it is fitting that the first disease attributed specifically to marine plastic debris has also been described in a seabird. In my view, plasticosis could be a sign that a new age of disease is upon us because of human overuse of plastics and other long-lasting contaminants, and their leakage into the environment.

In 2022, United Nations member nations voted to negotiate a global treaty to end plastic pollution, with a target completion date of 2024. This would be the first binding agreement to address plastic pollution in a concerted and coordinated manner. The identification of plasticosis in shearwaters shows that there is no time to waste.

Matthew Savoca, Postdoctoral researcher, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved