By Matthew Patterson, University of Oxford | –

(The Conversation) – On July 19 2022, the UK experienced its highest ever temperature. At 40.3℃ [104.5°F] (Coningsby, Lincolnshire), the temperature surpassed the previous record of 38.7℃ [101.6°F] (Cambridge) – a record that had been set a mere three years previously. My new study shows that this is part of a long-running trend of increasing heat extremes in north-west Europe.

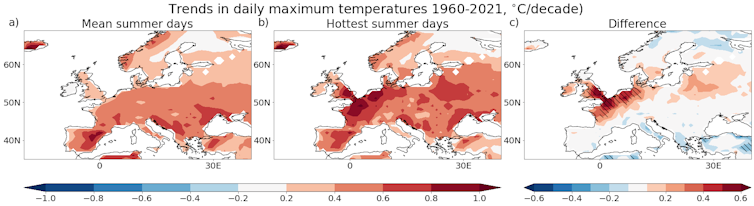

I examined trends in the temperature of the hottest summer day across north-west Europe and compared this to trends in average summer temperatures. My results, published in Geophysical Research Letters, suggest that between 1960 and 2021, north-west Europe has seen its hottest days warm by around 0.6℃ [1°F.] per decade – double the rate at which the region’s average summer days have warmed.

The trend suggests that the region could suffer extremely hot days more often in the future. But this trend isn’t captured in current climate models. While state-of-the-art climate models correctly simulated the trend in average summer temperatures, they failed to capture the enhanced warming of the extremes.

These same climate models are, however, often used to inform impact assessments of climate change. So their inability to simulate the magnitude of trends in extreme temperatures in north-west Europe means that the heat-related impacts of climate change may be underestimated in the short term – and inadequately prepared for as a result.

This is concerning. Infrastructure in north-west Europe is already poorly equipped to deal with extremely hot weather. And extreme heat can have several negative effects on human health and society.

Patterson (2023), CC BY-NC-ND

Imported air

The mechanism causing the temperature trends to differ for this region is not yet understood. But the hottest summer days in north-west Europe are often linked to the movement of hot air from over Spain or the Sahara. This was certainly the case in both July last year and July 2019.

Climate change is causing Spain and north Africa to warm faster than north-west Europe. My study found that between 1960 and 2021, the UK warmed by around 0.25℃ per decade compared to more than 0.5℃ per decade for much of Spain. Consequently, plumes of increasingly hot air that are carried north from these regions will bring high temperatures relative to the ambient air temperature of north-west Europe – these temperatures often exceed the threshold to be classified as “extreme”.

Climate models that show Spain and north Africa warming faster than north-west Europe also tend to see a greater rise in heat extremes in north-west Europe relative to mean warming in the future. Although adding further strength to this hypothesis, further work is needed to test the idea more rigorously.

Other possible hypotheses for the enhanced warming of heat extremes include changes to the atmospheric circulation patterns that drive heatwaves. Heatwaves are usually associated with high-pressure “anticyclonic” systems that push warm air northwards. These weather systems are accompanied by clear skies that allow the sun to heat the land.

There is some evidence that the increased occurrence of weather patterns like this could account for the rapid rise in very hot days.

Should we be worried?

The rising intensity of extreme heat in north-west Europe is worrying. Research has found that extreme heat can exacerbate respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and increase the risk of suffering heat stroke. This will put a strain on the health and emergency services.

Much of the infrastructure in the UK – and north-west Europe – is also not designed to deal with extreme heat. In the past, heatwaves have damaged road surfaces and have caused rails to buckle (where they expand and start to curve), leading to severe delays on rail services. On July 19 2022, for example, soaring temperatures meant no trains ran into or out of London King’s Cross rail station.

Homes in the UK also heat up much faster than those in other European countries. According to one study, the temperature inside an average British home will increase by 5℃ [9°F] in just three hours when the outside temperature is 30℃ [86°F.] That is more than double the rate at which homes across much of western Europe will gain heat.

Yet little is being done to help the same infrastructure cope with even hotter weather in the future. A recent report by the Climate Change Committee, an independent body advising the UK government on its response to climate change, found that the government is not taking sufficient action to adapt to climate change. The report highlighted the need to better heat-proof homes and mitigate wildfire risk as high temperatures become more common.

Over the past 60 years, north-west Europe’s hottest days have become much warmer. These findings indicate that the region is already dealing with the effects of climate change and underline the urgent need to adapt systems and infrastructure to help this area withstand it. From a scientific perspective, we must identify the reasons for the enhanced warming of heat extremes in order to improve current models and find out if this pattern is likely to continue in the future.![]()

Matthew Patterson, Postdoctoral Research Assistant in in Atmospheric Physics, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved