Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) –

Today, May 15, for the first time a commemoration will be held at the United Nations HQ in New York City of the 1948 ethnic cleansing of about half of all the Palestinians, the bulk of which was carried out by Jewish military forces, as Israeli intelligence admitted at the time. (See below, all the way down) The commemoration comes from a resolution of the UN General Assembly last fall.

In the morning, Palestine President Mahmoud Abbas will address a ‘high-level’ event with UN ambassadors and other officials in attendance.Then, the UN says, “A Special Commemorative Event will be held in the General Assembly Hall in the evening from 6 pm to 8 pm (NY Time). The event will bring to life the Palestinian journey and will aim at creating an immersive experience of the Nakba through live music, photos, videos, and personal testimonies.”

Although the expulsion of the Palestinians is an uncontested fact among professional historians, the very mention of it seems to send pro-Israel fanatics into a rage. U.S. Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy attempted and failed to stop a commemoration of the Nakbah by Rep Rashida Tlaib on Capitol Hill last week. The Israeli ambassador to the UN is calling on other ambassadors to boycott Monday’s events.

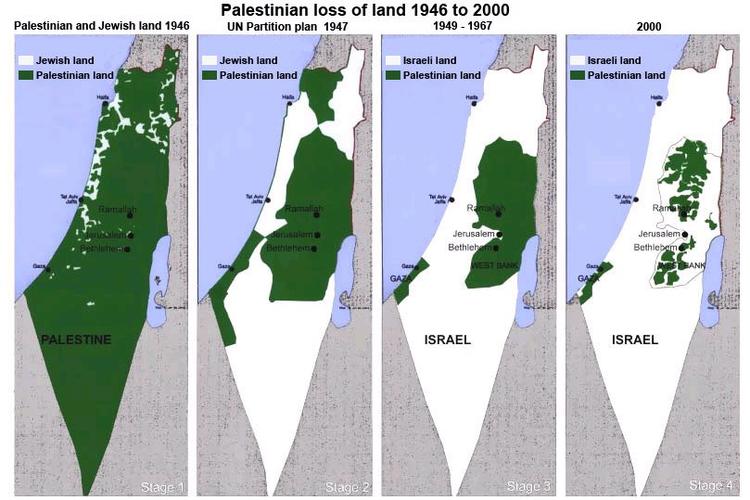

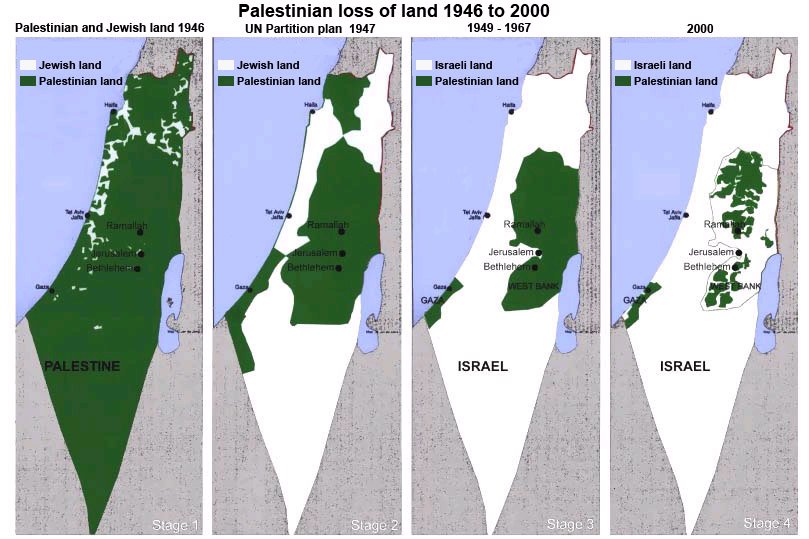

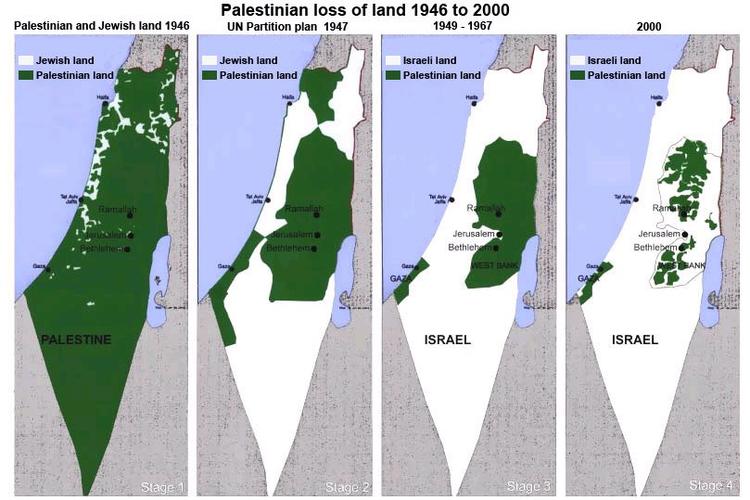

The below graphic tells the story of Palestinian displacement and descent into statelessness:

My simple posting of the map created a furor over a decade ago, about which I wrote:

- . . . I [had] mirrored a map of modern Palestinian history that has the virtue of showing graphically what has happened to the Palestinians politically and territorially in the past century.

Andrew Sullivan then mirrored the map from my site, which set off a lot of thunder and noise among anti-Palestinian writers like Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic, but shed very little light. (PS, the map as a hard copy mapcard is available from Sabeel.)

The map is useful and accurate. It begins by showing the British Mandate of Palestine as of the mid-1920s. The British conquered the Ottoman districts that came to be the Mandate during World War I (the Ottoman sultan threw in with Austria and Germany against Britain, France and Russia, mainly out of fear of Russia).

But because of the rise of the League of Nations and the influence of President Woodrow Wilson’s ideas about self-determination, Britain and France could not decently simply make their new, previously Ottoman territories into mere colonies. The League of Nations awarded them “Mandates.” Britain got Palestine, France got Syria (which it made into Syria and Lebanon), Britain got Iraq.

The League of Nations Covenant spelled out what a Class A Mandate (i.e. territory that had been Ottoman) was:

“Article 22. Certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory [i.e., a Western power] until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory.”

That is, the purpose of the later British Mandate of Palestine, of the French Mandate of Syria, of the British Mandate of Iraq, was to ‘render administrative advice and assistance” to these peoples in preparation for their becoming independent states, an achievement that they were recognized as not far from attaining. The Covenant was written before the actual Mandates were established, but Palestine was a Class A Mandate and so the language of the Covenant was applicable to it. The territory that formed the British Mandate of Iraq was the same territory that became independent Iraq, and the same could have been expected of the British Mandate of Palestine. (Even class B Mandates like Togo have become nation-states, but the poor Palestinians are just stateless prisoners in colonial cantons).

The first map thus shows what the League of Nations imagined would become the state of Palestine. The economist published an odd assertion that the Negev Desert was ’empty’ and should not have been shown in the first map. But it wasn’t and isn’t empty; Palestinian Bedouin live there, and they and the desert were recognized by the League of Nations as belonging to the Mandate of Palestine, a state-in-training. The Mandate of Palestine also had a charge to allow for the establishment of a ‘homeland’ in Palestine for Jews (because of the 1917 Balfour Declaration), but nobody among League of Nations officialdom at that time imagined it would be a whole and competing territorial state. There was no prospect of more than a few tens of thousands of Jews settling in Palestine, as of the mid-1920s. (They are shown in white on the first map, refuting those who mysteriously complained that the maps alternated between showing sovereignty and showing population). As late as the 1939 British White Paper, British officials imagined that the Mandate would emerge as an independent Palestinian state within 10 years.

In 1851, there had been 327,000 Palestinians (yes, the word ‘Filistin’ was current then) and other non-Jews, and only 13,000 Jews. In 1925, after decades of determined Jewish immigration, there were a little over 100,000 Jews, and there were 765,000 mostly Palestinian non-Jews in the British Mandate of Palestine. For historical demography of this area, see Justin McCarthy’s painstaking calculations; it is not true, as sometimes is claimed, that we cannot know anything about population figures in this region. See also his journal article, reprinted at this site. The Palestinian population grew because of rapid population growth, not in-migration, which was minor. The common allegation that Jerusalem had a Jewish majority at some point in the 19th century is meaningless. Jerusalem was a small town in 1851, and many pious or indigent elderly Jews from Eastern Europe and elsewhere retired there because of charities that would support them. In 1851, Jews were only about 4% of the population of the territory that became the British Mandate of Palestine some 70 years later. And, there had been few adherents of Judaism, just a few thousand, from the time most Jews in Palestine adopted Christianity and Islam in the first millennium CE all the way until the 20th century. In the British Mandate of Palestine, the district of Jerusalem was largely Palestinian.

The rise of the Nazis in the 1930s impelled massive Jewish emigration to Palestine, so by 1940 there were over 400,000 Jews there amid over a million Palestinians.

The second map shows the United Nations partition plan of 1947, which awarded Jews (who only then owned about 6% of Palestinian land) a substantial state alongside a much reduced Palestine. Although apologists for the Zionist movement say that the Zionists accepted this partition plan and the Arabs rejected it, that is not entirely true. Zionist leader David Ben Gurion noted in his diary when Israel was established that when the US had been formed, no document set out its territorial extent, implying that the same was true of Israel. We know that Ben Gurion was an Israeli expansionist who fully intended to annex more land to Israel, and by 1956 he attempted to add the Sinai and would have liked southern Lebanon. So the Zionist “acceptance” of the UN partition plan did not mean very much beyond a happiness that their initial starting point was much better than their actual land ownership had given them any right to expect.

The third map shows the status quo after the Israeli-Palestinian civil war of 1947-1948. It is not true that the entire Arab League attacked the Jewish community in Palestine or later Israel on behalf of the Palestinians. As Avi Shlaim has shown, Jordan had made an understanding with the Zionist leadership that it would grab the West Bank, and its troops did not mount a campaign in the territory awarded to Israel by the UN. Egypt grabbed Gaza and then tried to grab the Negev Desert, with a few thousand badly trained and equipped troops, but was defeated by the nascent Israeli army. Few other Arab states sent any significant number of troops. The total number of troops on the Arab side actually on the ground was about equal to those of the Zionist forces, and the Zionists had more esprit de corps and better weaponry.

The final map shows the situation today, which springs from the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank in 1967 and then the decision of the Israelis to colonize the West Bank intensively (a process that is illegal in the law of war concerning occupied populations).

There is nothing inaccurate about the maps at all, historically. Goldberg maintained that the Palestinians’ ‘original sin’ was rejecting the 1947 UN partition plan. But since Ben Gurion and other expansionists went on to grab more territory later in history, it is not clear that the Palestinians could have avoided being occupied even if they had given away willingly so much of their country in 1947.

The first original sin was the contradictory and feckless pledge by the British to sponsor Jewish immigration into their Mandate in Palestine, which they wickedly and fantastically promised would never inconvenience the Palestinians in any way. It was the same kind of original sin as the French policy of sponsoring a million colons in French Algeria, or the French attempt to create a Christian-dominated Lebanon where the Christians would be privileged by French policy.

The second original sin was the refusal of the United States to allow Jews to immigrate in the 1930s and early 1940s, which forced them to go to Palestine to escape the monstrous, mass-murdering Nazis.

The map attracted so much ire and controversy not because it is inaccurate but because it clearly shows what has been done to the Palestinians, which the League of Nations had recognized as not far from achieving statehood in its Covenant. Their statehood and their territory has been taken from them, and they have been left stateless, without citizenship and therefore without basic civil and human rights.

The map makes it easy to see this process. The map had to be stigmatized and made taboo. But even if that marginalization of an image could be accomplished, the squalid reality of Palestinian statelessness would remain, and the children of Gaza would still be being malnourished by the deliberate Israeli policy of blockading civilians. The map just points to a powerful reality; banishing the map does not change that reality.

So here are some comments about the Nakba or Catastrophe that befell the Palestinians in 1948:

The beginning of the Nakba:

The expulsion of Palestinians from what became Israel only became significant in April, 1948, with the impending departure of the British colonial forces, which freed the Haganah, the Irgun and other military bodies to act. In April and May, a quarter-million (out of 1.4 million) Palestinians were deliberately ethnically cleansed, according to an Israeli intelligence assessment carried out at the end of June. In June through late 1948, that number would be more than doubled to some 750,000, around half of all Palestinians. Although there was never an ‘expulsion order,’ the Israeli leader David Ben-Gurion signaled to his military commanders that it was undesirable to have many Palestinians inside the new Jewish state he was building. The commanders in any case saw all Palestinians as potential combatants and didn’t want to leave them in their rear as they advanced.

Even more egregious than the expulsions was Ben Gurion’s ironclad decision never to let any of the refugees return. They forfeited their homes, land, and other property, which were immediately seized by Jews. If the Palestinians ever received reparations for what was taken from them it would be worth billions.

Here are some telling excerpts from Israeli Intelligence Service, Arab Section, Hashomer Hatzair (Yad Yaari) Archive, file 95-35.27(3), “Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948, dated June 30, 1948 (translated by The Akevot Institute, Akevot.org from the Hebrew original:

b. The rate of migration from the State of Israel until June 1, 1948 (including Jenin and the south, until June 14, 1948):

1. Approximately 180 Arab villages empty.

2. 3 cities entirely empty, and in Haifa, only 5,000 residents . . .

6. Total who left the State of Israel 239,000 . . .

d. The number of Arabs who remained in the State of Israel:

1. No. of urban dwellers who remained in the State of Israel 5,000

2. No. of villagers who remained in the State of Israel 38,000

3. No. of Bedouins (in the Negev) who remained in the State of Israel 60,000 103,000

4. 39 inhabited Arab villages remained in the country (With respect to some, there is no information that they left).

5. Only one of the cities of the State of Israel has an Arab population (Haifa: 5,000 persons) .

e. The rate of migratory movement in Eretz Yisrael as a whole: The number of displaced Arabs is 391,000. (As stated in the introduction, the margin of error is 10%-15%) . . .

The fourth phase: This stage spans the month of May. It is the principal and decisive phase of the Arab migration in Eretz Yisrael. A migration psychosis begins to emerge, a crisis of confidence with respect to Arab strength. As a result, migration in this sage is characterized by:

Major increase iin migration trajectory in Tel-Hai district.

“ “ “ “ “ “ Gilboa “ . “ “ “ “ “ “ Jaffa “ . “ “ “ “ “ “ Western Galilee “ .

Evacuation in Negev villages takes place in this month. On the other hand, the Central Region enters this phase having peaked already, with most villages having been evacuated. Therefore, for the Central Region, this phase is the “final stretch”. Because the number of remaining villages in the Central Region was small, the seemingly significant decrease felt here is no more than the final touch. The only place where a true decrease is felt in this month is the Sea of Galilee area.

4 Conclusion: The mass migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs took place in April-May. May was a climax and recorded as the month during which most of the Arab migration took place, or, more precisely, the Arab flight.

Causes of Arab migration

a. General . . .

In reviewing the factors that affected migration, we list the factors that had a definitive effect on population migration. Other factors, localized and smaller scale, are listed in the special reviews of migration movement in each district. The factors, in order of importance, are:

1. Direct Jewish hostile actions against Arab communities.

2. Impact of our hostile actions against communities neighboring where migrants lived (here – particularly – the fall of large neighboring communities).

3. Actions taken by the Dissidents [Irgun, Lehi].

4. Orders and directives issued by Arab institutions and gangs.

5. Jewish Whispering operations [psychological warfare] intended to drive Arabs to flee.

6. Evacuation ultimatums.

7. Fear of Jewish retaliation upon a major Arab attack on Jews.

8. The appearance of gangs and foreign fighters near the village.

9. Fear of an Arab invasion and its consequences (mostly near the borders).

10. Arab villages isolated within purely Jewish areas.

11. Various local factors and general fear of what was to come.

5

b. The factors in detail.

Without a doubt, hostilities were the main factor in the population movement. Each and every district underwent a wave of migration as our actions in that area intensified and expanded. In general, for us, the month of May signified a transition into wide-scale operations, which is why the month of May involved the evacuation of the maximum number of locales. The departure of the English, which was merely the other side of the coin, did, of course, help evacuation, but it appears that more than affecting migration directly, the British evacuation freed our hands to take action. Note that it was not always the intensity of the attack that was decisive, as other factors became particularly prominent – mostly psychological factors. The element of surprise, long stints of shelling with extremely loud blasts, and loudspeakers in Arabic proved very effective when properly used (mostly Haifa!);

It has, however, been proven, that actions had no lesser effect on neighboring communities as they did on the community that was the direct target of the action. The evacuation of a certain village as a result of us attacking it swept with it many neighboring villages.

The impact of the fall of large villages, centers, towns or forts with a large concentration of communities around them is particularly apparent. The fall of Tiberias, Safed, Samakh, Jaffa, Haifa and Acre produced many large migration waves. The psychological motivation at work here was “If the mighty have fallen….”. In conclusion, it can be said that at least 55% of the overall migration movement was motivated by our actions and their impact.

The actions of the Dissidents and their impact as migration motivators:

The actions of the Dissidents as migration motivators were particularly apparent in the Jaffa Tel-Aviv area; the Central Region, the south and the Jerusalem area. In other places, they did not have any direct impact on evacuation.

Dissidents’ actions with special impact:

Deir Yassin, the kidnapping off five dignitaries from Sheikh Muwannis, other actions in the south. The Deir Yassin action had a particular impact on the Arab psyche. Much of the immediate fleeing seen when we launched our attacks, especially in the center and south, was panic flight resulting from that factor, which can be defined as a decisive catalyst. There was also panic flight spurred by actions taken by the Irgun and Lehi themselves.

Many Central Region villagers went into flight once the dignitaries from Sheikh Muwannis were kidnapped. The Arab learned that it was not enough to make a deal with the Haganah, and there were “other Jews”, of whom one must be wary, perhaps even more wary than of members of the Haganah, which had no control over them. The Dissidents’ effect on the evacuation of Jaffa city and the Jaffa rural area is clear and definitive – decisive and critical impact among migration factors here. If we were to assess the contribution made by the Dissidents as factors in the evacuation of Arabs in Eretz Yisrael we would find that they had about 15% direct impact on the total intensity of the migration.

To summarize the previous sections, one could, therefore, say that the impact of “Jewish military action” (Haganah and Dissidents) on the migration was decisive, as some 70% of the residents left their communities and migrated as a result of these actions. . . .

Jewish psychological warfare to make Arab residents flee.

This type of action, when considered as part of the national phenomena, was not a factor with a broad impact. However, 18% of all the villages in the Tel-Hai area, 6% of the village in the central region, and 4% of the Gilboa region villages were evacuated for this reason.

Where in the center and the Gilboa regions such actions were not planned or carried out on a wide scale, and therefore had a smaller impact, in the Tel-Hai district, this type of action was planned and carried out on a rather wide scale and in an organized fashion, and therefore yielded greater results. The action itself took the form of “friendly advice” offered by Jews to their neighboring Arab friends. This type of action drove no more than 2% of the total national migration.

Our ultimatums to Arab villages: This factor was particularly felt in the center, less so in the Gilboa area and to some extent in the Negev. Of course, these ultimatums, like the friendly advice, came after the stage had been set to some extent by hostilities in the area. Therefore, these ultimatums were more of a final push than the decisive factor. Two percent of all evacuated village locales in the country were evacuated due to ultimatums.

Fear of reprisals. This evacuation, which can also be termed “organized evacuation” came mostly after actions against Jews had been launched from inside the village or its vicinity. An Arab attack on a Jewish convoy (the “Ehud” convoy on route to Ahiam, for instance), or a Jewish Arab battle (the Mishmar HaEmek front, the Gesher front, the attack on Lehavot, etc.), automatically impacted the evacuation of nearby villages. One percent of evacuated Arab locales left due to this factor.

All other factors listed . . . together account for no more than 1%.

General fear. Although this factor is listed last, it did have a sizeable impact and played a significant part in the evacuation. Still, given its generality, we chose to conclude with it. When the war began, various reasons caused general fear within the strata of the Arab public, which chose to emigrate for no apparent, particular, reason. However, this general fear was the primary manifestation of the “crisis of confidence” in Arab strength.

It is reasonable to assume that 10% of all villages evacuated for this reason, such that, in effect, the impact of the “crisis of confidence” was the third most important factor following our actions and the actions of the Dissidents and their impact. Local factors also had a rather marked impact on migration movement: failed negotiations, plans to impose restricted settlement, inability to adjust to certain realities, failed negotiations for maintaining the status-quo or non-aggression agreements – all had an effect in certain areas (for instance, the south), but fail to have any presence in other areas. It can be said that 8%-9% of the evacuated villages in the country were evacuated because of various local factors. . . .

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved