By Jennifer Greenburg, University of Sheffield | –

A US Army handbook from 2011 opens one of its chapters with a line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Young British Soldier. Written in 1890 upon Kipling’s return to England from India, an experienced imperial soldier gives advice to the incoming cohort:

When you’re wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains, And the women come out to cut up what remains …

The handbook, distributed in 2011 at the height of the US’s counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, invoked Kipling and other imperial voices to warn its soldiers that:

Neither the Soviets in the early 1980s nor the west in the past decade have progressed much beyond Kipling’s early 20th-century warning when it comes to understanding Afghan women. In that oversight, we have ignored women as a key demographic in counterinsurgency.

Around this time, a growing number of US military units were – against official military policy – training and posting all-women counterinsurgency teams alongside their male soldiers.

Women were still banned from direct assignment to ground combat units. However, these female soldiers were deployed to access Afghan women and their households in the so-called “battle for hearts and minds” during the Afghanistan war, which began on October 7 2001 when the US and British militaries carried out an air assault, followed by a ground invasion, in response to the September 11 attacks.

Cpl. Meghan Gonzales/DVIDS

And these women also played critical roles in gathering intelligence. Their sexuality – ironically, the basis of the excuse the US military had long given for avoiding integrating women into combat units – was now seen as an intelligence asset, as the army handbook made clear:

Like all adolescent males, young Afghan males have a natural desire to impress females. Using this desire to interact with and impress females can be advantageous to US military forces when done respectfully to both the female soldier and the adolescent Afghan males. Female soldiers can often obtain different and even more in-depth information from Afghan males than can male soldiers.

Whether collecting intelligence or calming victims of a US special forces raid, female soldiers – often despite a lack of proper training – played a central yet largely invisible role in the Afghanistan war. Their recollections of what they experienced on these tours call into question official narratives both of women breaking through the “brass ceiling” of the US military, and the war having been fought in the name of Afghan women’s rights and freedom.

Since the US’s final withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban’s rollback of women’s rights has concluded a brutal chapter in a story of competing feminisms over the past two decades of war.

Cpl. Meghan Gonzales/DVIDS

Female counterinsurgency teams in Afghanistan

Between 2010 and 2017, while conducting research at six US military bases and several US war colleges, I met a number of women who spoke of having served on special forces teams and in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. This was surprising as women were then still technically banned from many combat roles – US military regulations only changed in 2013 such that, by 2016, all military jobs were open to women.

Fascinated by their experiences, I later interviewed 22 women who had served on these all-female counterinsurgency teams. The interviews, alongside other observations of development contractors on US military bases and the ongoing legacies of US imperial wars, inform my new book At War with Women: Military Humanitarianism and Imperial Feminism in an Era of Permanent War.

By 2017, enough time had lapsed that the women could speak openly about their deployments. Many had left the military – in some cases disenchanted by the sexism they confronted, or with the idea of returning to an official job in logistics having served on more prestigious special forces teams.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

In 2013, Ronda* supported a mission deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second-largest city. She was one of only two women living on a remote base with the Operational Detachment Alpha – the primary fighting force for the Green Berets (part of the US Army’s special forces).

For Ronda, one of the most rewarding aspects of this deployment was the image she carried of herself as a feminist example for Afghan women. She recalled:

Just letting the girls see there’s more out there [in the wider world] than what you have here, that was very empowering. I think they really appreciated it. In full kit I look like a dude, [but] that first instance when you take off your helmet and they see your hair and see you are female … A lot of times they have never seen a female before who didn’t just take care of the garden and take care of the kids. That was very empowering.

Cpl. Meghan Gonzales/DVIDS

Amanda, who had been on a similar mission to Uruzgan province in southern Afghanistan a year earlier, also described inspiring local women – in her case, via stories she shared through her interpreter of life in New York City, and what it was like to be a female soldier. Amanda lived alongside the male soldiers in an adobe hut with a thatched roof, and was unable to shower for the full 47 days of the mission. But she recalled going out into the village with pride:

You see the light, especially in the females’ eyes, when they see other females from a different country – [it] kind of gives them perspective that there is more to the world than Afghanistan.

Publicly, the US military presented its female counterinsurgency teams as feminist emblems, while keeping their combat roles and close attachment to special forces hidden. A 2012 army news article quoted a member of one female engagement team (FET) describing the “positive responses from the Afghan population” she believed they had received:

I think seeing our FET out there gives Afghan women hope that change is coming … They definitely want the freedom American women enjoy.

However, the US military’s mistreatment of its female workforce undermines this notion of freedom – as do the warped understandings of Afghan culture, history and language that both male and female soldiers brought with them on their deployments. Such complexity calls into question US military claims of providing feminist opportunities for US women, and as acting in Afghan women’s best interests.

As a logistics officer, Beth had been trained to manage the movement of supplies and people. She said she was ill-prepared for the reality she confronted when visiting Afghan villages with one of the cultural support teams (CSTs), as they were also known, in 2009.

Beth’s pre-deployment training had included “lessons learned” from the likes of Kipling and Lawrence of Arabia. It did not prepare her to understand why she encountered such poverty when visiting Afghan villages. She recalled:

Imagine huts – and tons of women, men and children in these huts … We had to tell these women: ‘The reason your children are getting sick is because you’re not boiling your water.’ I mean, that’s insane. Look at when the bible was written. Even then, people knew how to boil their water – they talked about clean and unclean, kosher, and that they know what’s going to rot. How did Jesus get the memo and you didn’t?

Jennifer Greenburg, Author provided

‘Ambassadors of western feminism’

By observing lessons in military classrooms, I learned how young US soldiers (men and women) went through pre-deployment training that still leaned on the perspectives of British colonial officers such as T.E. Lawrence and C.E. Callwell. There was a tendency to portray Afghan people as unsophisticated children who needed parental oversight to usher them into modernity.

US military representations of Afghan women as homogeneous and helpless, contrasting with western women as models of liberation, also ignored Afghan and Islamic feminist frameworks that have long advocated for women’s rights. The notion of US female soldiers modelling women’s rights was often linked with representations of Afghan people as backward and needing models from elsewhere.

To skirt the military policy that in the mid-2000s still banned women from direct assignment to ground combat units, female soldiers were “temporarily attached” to all-male units and encouraged not to speak openly about the work they were doing, which typically entailed searching local women at checkpoints and in home raids.

Rochelle wrote in her journal about her experiences of visiting Afghan villages: “Out the gate I went, [with] headscarf and pistol …” Like Beth’s use of a biblical reference to explain the Afghan villages she confronted, Rochelle placed Afghanistan far backward in time. In one diary entry about a village meeting, she reflected:

For years, I have always wondered what it would be like to live in the Stone Age – and now I know. I see it every day all around me. People walking around in clothes that haven’t been washed, ones they have worn for years. Children with hair white from days of dust build-up. Six-year-old girls carrying around their baby brothers. Eyes that tell a story of years of hardship. Houses made of mud and wooden poles, squares cut out for windows. Dirty misshapen feet.

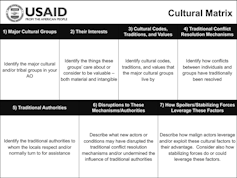

USAID, Author provided

When Rochelle was not accompanying the male patrols, she was visiting girls’ schools and holding meetings with Afghan women about how her unit could help support income-generating opportunities for women, such as embroidery or selling food. Her logic, that this would reduce Taliban support and recruitment, echoed USAID programmes that still today claim targeted economic opportunity can “counter violent extremism”.

Amelia, a female soldier attached to a special forces mission, spoke of how she was an asset because:

We were not threatening, we were just there. For Afghan men, we were fascinating because we were these independent women in a different role than they see for most women there. And we were non-threatening to them, so they could talk to us openly.

Strikingly, Amelia admitted that she and other female soldiers played a similar role for their American counterparts too:

For the [male] marines, just having us there helped kind of calm things down. We would do things to try to give back to them – like we baked for them frequently. That was not our role and I don’t want anyone to think that we were a “baking team”, but we would do things like that and it really helped. Like a motherly touch or whatever. We would bake cookies and cinnamon buns. It really helped bring the team together and have more of a family feeling.

Amelia’s clear apprehension at her unit being seen as the “baking team” speaks to how they were incorporated into combat through reinforcement of certain gender stereotypes. These women used “emotional labour” – the work of managing, producing and suppressing feelings as part of one’s paid labour – both to counsel the male soldiers with whom they were stationed, and to calm Afghan civilians after their doors had been broken down in the middle of the night.

But the women I met also revealed a culture of sexist abuse that had been exacerbated by the unofficial nature of their combat roles in Afghanistan and Iraq. Soldiers who did not want women in their midst would joke, for example, that CST actually stood for “casual sex team”. Such treatment undermines the US military’s representations of military women as models of feminist liberation for Afghan women.

Jennifer Greenburg, Author provided

‘It was the best and the worst deployment’

Beth’s first deployment to Afghanistan in 2009 was to accompany a small group of Green Berets into an Afghan village and interact with the women and children who lived there. One of her strongest memories was figuring out how to shower once a week by crouching under a wood palate and balancing water bottles between its slats.

Beth’s role was to gather information about which villages were more likely to join the US military-supported internal defence forces – a cold war counterinsurgency strategy with a history of brutalising countries’ own citizens. To elicit feelings of security and comfort in those she encountered when entering an Afghan home or searching a vehicle, she described adjusting her voice tone, removing her body armour, and sometimes placing her hands on the bodies of Afghan women and children.

But this “kinder and gentler” aspect of her work was inseparable from the home raids she also participated in, during which marines would kick down the doors of family homes in the middle of the night, ripping people from their sleep for questioning, or worse.

Women like Beth were exposed to – and in a few cases, killed by – the same threats as the special forces units to which they were unofficially attached. But the teams’ hidden nature meant these women often had no official documentation of what they did.

If they returned home injured from their deployment, their records did not reflect their attachment to combat units. This meant they were unable to prove the crucial link between injury and service that determined access to healthcare. And the women’s lack of official recognition has since posed a major barrier to being promoted in their careers, as well as accessing military and veteran healthcare.

While Beth said she was “lucky” to have come home with her mental health and limbs intact, many of her peers described being unable to sleep and suffering from anxiety, depression and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of their continued exposure to stressful combat situations such as night raids.

Six months into her deployment, Beth’s female partner was riding in a large armoured vehicle when it ran over an explosive device. “Luckily”, as Beth put it, the bomb exploded downwards, blowing off four of the vehicle’s wheels and sending a blast through the layer of rubber foam on which her partner’s feet rested. She was medevacked out of the combat zone with fractured heels, along with six other men.

Technically, Beth was always supposed to have a female partner when working for a cultural support team, but no replacement came. Her mission changed and she became the only woman assigned to support a group of marines stationed on a remote base. There were only a handful of other women on the base, and Beth lived alone in a repurposed shipping container sandwiched between housing for 80 men.

Beth said the marines spread false rumours about her. Other women I spoke with indicated that there was a widespread culture of degrading women like Beth in the US military at this time – just as its leaders were publicly disavowing the military’s epidemic of sexual assault and rape.

As Beth described her treatment on the second part of her deployment in Afghanistan, her eyes widened. She struggled to find the words that eventually came out:

It was the best and the worst deployment. On some level, I did things that I will never do again – I met some great people, had amazing experiences. But also, professionally, as a captain in the Marine Corps, I have never been treated so poorly in my life – by other officers! I had no voice. Nobody had my back. [The marines] didn’t want us there. These guys did not want to be bringing women along.

Beth described how one of the male soldiers lied to her battalion commander, accusing her of saying something she didn’t say – leading to her being removed from action and being placed under a form of custody:

I got pulled back and sat in the hot-seat for months. It was bad. That was a very low point for me.

‘Women as a third gender’

A narrow, western version of feminism – focused on women’s legal and economic rights while uncritical of the US’s history of military interventions and imperialistic financial and legal actions – helped build popular support for the Afghanistan invasion in 2001. On an individual level, women like Beth made meaning of their deployments by understanding themselves as modern, liberated inspirations for the Afghan women they encountered.

Staff Sgt. Whitney Hughes/DVIDS

But in reality, the US military did not deploy women like Beth with the intention of improving Afghan women’s lives. Rather, special forces recognised Afghan women as a key piece of the puzzle to convince Afghan men to join the internal defence forces. While male soldiers could not easily enter an Afghan home without being seen as disrespecting women who lived there, the handbook for female engagement teams advised that:

Afghan men often see western women as a “third gender” and will approach coalition forces’ women with different issues than are discussed with men.

And a 2011 Marine Corps Gazette article underlined that:

Female service members are perceived as a “third gender” and as being “there to help versus there to fight”. This perception allows us access to the entire population, which is crucial in population-centric operations.

The use of “third gender” here is surprising because the term more often refers to gender identity outside of conventional male-female binaries. In contrast, military uses of such language reinforced traditional gender expectations of women as caregivers versus men as combatants, emphasising how women entered what were technically jobs for men by maintaining these gender roles.

The female counterinsurgency teams were intended to search Afghan women and gather intelligence that was inaccessible to their male counterparts. Beth had volunteered for these secretive missions, saying she was excited to go “outside the wire” of the military base, to interact with Afghan women and children, and to work with US special operations.

Initially, she was enthusiastic about the tour, describing her gender as an “invaluable tool” that allowed her to collect information which her male counterparts could not. She went on home raids with the marines and would search women and question villagers.

Technically, the US military has strict rules about who is allowed to collect formal intelligence, limiting this role to those trained in intelligence. As a result, Beth explained:

Just like any other team going out to collect information, we always steer clear of saying “collect” [intelligence]. But essentially that’s exactly what we were doing … I won’t call them a source because that is a no-no. But I had individuals who would frequent me when we were in particular areas … [providing] information we were able to elicit in a casual setting instead of running a source and being overt.

‘A completely different energy’

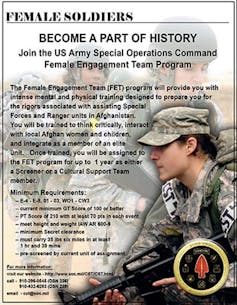

US Army

Cindy deployed with a US Army Ranger regiment to Afghanistan in 2012. Having recently graduated from one of the military academies, an advertisement caught her eye: “Become a part of history. Join the US Army Special Operations Command Female Engagement Team Program.”

She was drawn in by the high physical bar and intellectual challenge of jobs in special operations from which the military technically excluded her. Describing the process of being selected for the female unit as a “week from hell”, Cindy said she was proud of “being where it’s hardest” and “the sense of duty, obligation”.

While she was completing her training, Cindy’s friend from airborne school was killed by an explosion in October 2011, while accompanying an Army Ranger team on a night raid of a Taliban weapons maker’s compound in Kandahar. This was Ashley White-Stumpf, subject of the bestselling book Ashley’s War, which is now being adapted into a film starring Reese Witherspoon. She was the first cultural support team member to be killed in action, and her funeral brought this secret programme into a very public light.

Her death cast a shadow on the excitement Cindy had initially felt. To confuse matters, the dangers that White-Stumpf (and now Cindy) faced were publicly invisible, given that women were banned from being officially attached to special forces combat units. When female soldiers did appear in public relations photographs, it was often handing out soccer balls or visiting orphanages.

Staff Sgt. Kelly Lecompte/DVIDS via Wikimedia

Yet once deployed, Cindy was attached to a “direct action” unit – the special forces portrayed in action movies kicking down doors, seizing documents and capturing people. This meant that while special forces carried out their mission, her job was:

To interact with women and children. To get information, or [find out] if there were nefarious items that were hidden under burkas and things of that nature.

She explained how “you have different tools as a woman that you can use that I don’t think a man would be successful in” – offering the example of a little boy in a village who her team thought knew something. A ranger was questioning the little boy, who was terrified of how, in her words, this male soldier “looked like a stormtrooper, wearing his helmet and carrying a rifle”. In contrast, Cindy explained:

For me to kneel next to the little kid and take off my helmet and maybe put my hand on his shoulder and say: “There, there” – I can do that with my voice, [whereas] this guy probably could not or would not. And that kid was crying, and we couldn’t get anything out of him. But you can turn the tables with a completely different energy.

Cindy told me proudly how it took her just 15 minutes to identify the correct location of the Taliban activity, when her unit had been in the wrong location. She, like many of the women I spoke to, painted a picture of using emotional labour to evoke empathy and sensitivity amid violent – and often traumatic – special operations work.

‘I’ve had so much BS in my career’

The women I interviewed were operating in the same permissive climate of sexual harassment and abuse that later saw the high-profile murders of the servicewoman Vanessa Guillén at Fort Hood military base in Texas in 2020, and the combat engineer Ana Fernanda Basaldua Ruiz in March 2023.

Before their deaths, both Latinx women had been repeatedly sexually harassed by other male soldiers and had reported incidents to their supervisors, who failed to report them further up the chain of command. Such cases overshadowed any excitement about the recent ten-year anniversary of women formally serving in ground combat roles in the US military.

Mollie deployed to Afghanistan as part of a female engagement team in 2009. Her career up to then had been chequered with discriminatory experiences. In some cases, there were subtle, judgmental looks. But she also described overt instances, such as the officer who, when told of her impending arrival on his unit, had responded bluntly: “I don’t want a female to work for me.”

Mollie said she saw the FET as a way to showcase women’s skill and value within a masculinist military institution. She felt tremendous pride for the “20 other strong women” she worked with, whose adaptability she was particularly impressed with:

During the FET, I saw such great women. It frustrates me that they have to put up with this [sexism] … I’ve had so much BS like that throughout my career. Seeing how amazing these women were in high-stress situations – I want to stay in and continue to fight for that, so junior marines don’t have to put up with the same sorts of sexist misogynist comments that I did.

Mollie said the experience on the FET changed her, describing herself emerging as an “unapologetic feminist” responsible for more junior servicewomen. This encouraged her to re-enlist year after year. But for other women, deploying in capacities from which they were normally excluded, only to then return to gender-restricted roles, was a good reason to quit after their contract was up. As was, for many, the continued background of resistance and abuse from male colleagues.

A 2014 study of the US military found that “ambient sexual harassment against service women and men is strongly associated with risk of sexual assault”, with women’s sexual assault risk increasing by more than a factor of 1.5 and men’s by 1.8 when their workplace had an above-average rate of ambient sexual harassment. In 2022, the US military admitted that the epidemic of sexual assault within military ranks had worsened in recent years, and that existing strategies were not working.

‘Magnitude of regrets’

Amid the chaotic withdrawal of US and international forces from Afghanistan in August 2021, marines threw together another female engagement team to search Afghan women and children. Two of its members, maintenance technician Nicole Gee and supply chief Johanny Rosario Pichardo, died in a suicide bomb attack during the evacuation that killed 13 soldiers and at least 170 Afghans.

Media coverage remembered Gee cradling an Afghan infant as she evacuated refugees in the days leading up to the attack, underscoring how female soldiers like her did high-risk jobs that came into being through gender expectations of women as caregivers.

Writing to me in 2023, ten years after her deployment to Afghanistan, Rochelle reflected that the departure of US soldiers could be “a whirlwind of emotions if you let it”. She added: “My anger lies with the exit of our own [US forces]. The magnitude of regrets, I hope, lay heavy on someone’s conscience.”

The experiences of Rochelle and other female soldiers in Afghanistan complicate any simplistic representations of them as trailblazers for equal rights in the US military. Their untreated injuries, unrecognised duties, and abusive working conditions make for a much more ambivalent blend of subjugation and pathbreaking.

And even as their position helped formalise the role of US women in combat, this happened through the reinforcement of gender stereotypes and racist representations of Afghan people. In fact, Afghan women had long been mobilising on their own terms – largely unintelligible to the US military – and continue to do so, with extraordinary bravery, now that the Taliban is back in control of their country.

It is devastating, but not surprising, that the military occupation of Afghanistan did not ultimately improve women’s rights. The current situation summons feminist perspectives that challenge war as a solution to foreign policy problems and work against the forms of racism that make people into enemies.

Following the withdrawal from Afghanistan, US Army female engagement teams have been reassembled and deployed to train foreign militaries from Jordan to Romania. As we enter the third decade of the post-9/11 wars, we should revisit how these wars were justified in the name of women’s rights, and how little these justifications have actually accomplished for women – whether in the marine corps barracks of Quantico, Virginia, or on the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan.

*All names and some details have been changed to protect the identities of the interviewees.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Jennifer Greenburg, Lecturer in International Relations, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved