Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – High daytime temperatures in the Mediterranean basin are disrupting life in many ways, in Spain, Morocco, Greece, Turkey and elsewhere.

Tourists in Greece suffered frustrations on Friday when government authorities abruptly closed the Parthenon from midday until evening. There were fears that the tourists up there would have a heat stoke, with the high forecast as much as 104°F (40C ).

Image by nonbirinonko from Pixabay

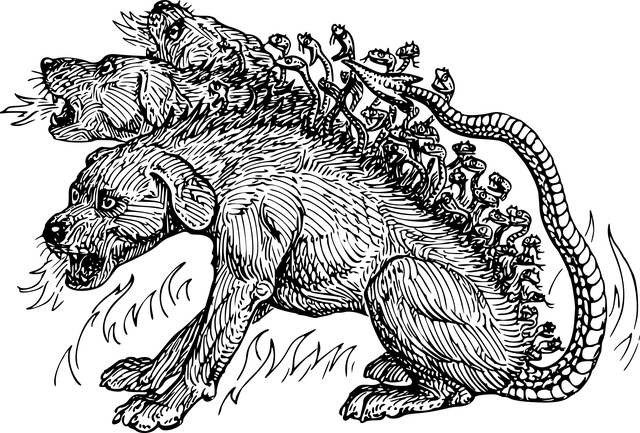

Wired discusses the controversy over the informal name for this heat wave, Cerberus, which started with the Italian meteorological society. The reference is to Kerberos in Greek mythology, the many-headed dog who guarded the gates of the underworld to keep its inmates from leaving.

One problem with naming the heat wave with reference to Cerberus is that the realm of the death-god Hades in Greek mythology was not hot. It was a cold, dank and grim labyrinth.

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

It was thinkers in the later Christian and Muslim traditions who imagined Gehenna or hell as hot. That is certainly the case in the Qur’an, which talks of sinners being grilled like kebabs, or words to that effect.

So a heat wave shouldn’t be named Cerberus.

The god of fire and volcanoes and forges was Hephaistos (Hephaestus). The modern Greek word for volcano, efaisteio, comes from his name. He’d be a better classical referent for heat waves than the three-headed, or a hundred-headed, or the snake-headed Cerberus. Different classical authors described him differently.

But back to the Parthenon. It is named for Athena, the “virgin” (modern Greek parthena), who lived at the Acropolis along with eleven other major Olympian gods — Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Apollo, Artemis, Hephaistos, Ares, Aphrodite, Hermes, and Dionysos, who are represented at the eastern freize of the Parthenon.

Image by Gonbiana from Pixabay

The ancient Greek myths are suggestive for our own climate problems, which are taking on cosmic dimensions.

Hephaistos midwifed Athena’s birth. Her father, Zeus, had a splitting headache and Hephaistos, being a god of crafts, thought he knew what to do about it. He grabbed an axe and split Zeus’s head open. There emerged Athena, fully grown and in armor, bearing arms.

Athena then had to fight her uncle, the sea god Poseidon, for control of Mt. Olympus and the city around it. Athena won, in an early feminist victory over male chauvinism. Hence, Greece’s capital is called Athens. I suppose one could interpret her myth as a victory of land-based civilization over the threatening storm surges and floods of the sea.

But the very god of fire who midwifed her birth from the head of Zeus now threatens her city. The twelve gods, the Dodecatheon, can’t be approached in the fiery midday over which Hephaistos presides.

That mythological sites of ancient civilization, and mythological figures, suggest themselves so readily to describe our climate crisis points to how overwhelming it increasingly seems. We feel the need to evoke the mythological when talking about it.

Some have suggested, the Wired article reports, that these mythological images are too frightening for the public. From my point of view, the public isn’t nearly frightened enough, otherwise there would be way more solar panels on rooftops and people would be voting for green candidates, not fascist or neoliberal ones.

It is true, however, that the public should be constantly reminded that the climate crisis is a challenge we can meet as a species. If we go to zero carbon by 2050, the increase in global heating will immediately stop. And gradually, all the extra CO2 in the atmosphere will be scrubbed out by the oceans and other carbon sinks. Another 150 years and we could get back almost to normal.

If Athena could defeat Poseidon, we too can defeat the natural disasters that threaten our cities. But only if we take this threat very, very seriously. It isn’t just an annoyance to tourists that we are speaking about. It is an accelerating, profound change in the conditions of our existence.

It is cosmic. It is mythological.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved