By Victor Galaz, Stockholm University | –

When asked to situate the world’s most iconic rainforest on a map, most people will pinpoint Brazil. And given the intense media coverage of the country’s deforestation and fires – concerns reached a peak under former president Jair Bolsonaro and his free-for-all approach – they might also imagine a thick black soot clinging to the remaining trees. While newly re-elected president Lula da Silva has vowed to prioritize the Amazon forest and sparked hope among environmentalists, deforestation in the Brazilian section of Amazon remains of deep concern.

That interest is only set to grow as Brazil gets ready to host a high-level meeting to renew the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) in the northern town of Belem on 8 and 9 August. Bringing together the eight countries containing the Amazon forest – Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela – along with senior officials from the United States and France, the event will enable them to discuss how to attract investment, fight deforestation, protect indigenous communities and encourage sustainable development.

The meeting will also be the occasion for sustainability scientists such as ourselves to draw attention to one of the Amazonian ecosystems that will be just as vital to protect if we are to limit global warming to the safer threshold of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels: Bolivia.

One of the highest carbon-emitting countries per capita

I have studied the flows that contribute to deforestation in the Amazon for more than five years. Earlier this year, I met with academics, environmental NGOs, smallholder farmers, and multilateral development banks in Bolivia to learn more about their work to protect the Bolivian Amazon.

Bolivia is not only at the centre of the current international rush for lithium. It is also one of the world leaders in deforestation. According to Global Forest Watch, the country lost more than 3,3 million hectares of humid primary forest from 2002 to 2021 to deforestation, or the equivalent of 4 million soccer fields, with an exponential growth in deforestation rates of more than 5.5% per year over the last two decades.

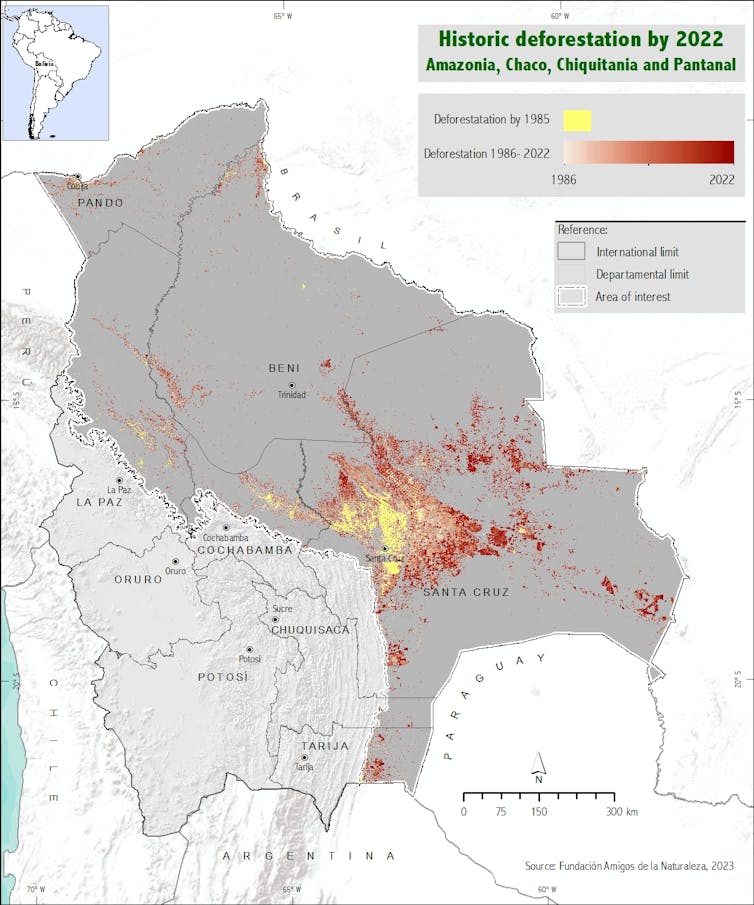

Bolivia’s forests have also increasingly been forced to cope with a combination of drought and large wildfires. In 2020 alone, 4,5 million hectares were affected by such fires, of which more than 1 million hectares took place in protected areas (data from Fundación Amigos de la Naturaleza) – and the deforestation trend is worsening (see Figure 1). As a result, Bolivia has placed itself at the top of carbon-emitting countries per capita, with emissions of 25 tCO2eq per person per year – more than five times higher than the global average, ahead of large economies like the United States and the United Arab Emirates.

Fundación amigos de la naturaleza (FAN), Bolivia, CC BY-NC

Accelerated deforestation might seem paradoxical in a country known internationally for its commitment to the “Rights of Mother Earth”. But it seems that the government has chosen to prioritize economic development based on natural resources over its promises to become stewards of Nature.

The accelerated loss of tropical rainforest is the result of destructive and familiar combination: increased global demand for commodities such as soy and cattle, and extractive national and regional policies with the explicit ambition to boost economic growth with little consideration on its environmental impact.

Soybean production has accelerated from negligible levels in 1970 to almost 1.4 million hectares in 2020, and 5 million hectares deforested since 2001 is mainly used for cattle. A similar trend can be observed for the export of beef in the last years, as well as for mining.

Victor Galaz, Author provided

Between 2015 and 2021, the number of mining concessions in the country’s Amazon regions (La Paz, Beni and Pando) has increased from 88 to 341 while the mining area (cuadriculas in Spanish) have increased from 3,789 to 15,710 (+414%). According to Bolivian mining law, a cuadricula is a square of 500 meters per side, with a total surface area of 25 hectares, according to the Study Center for Labor and Agrarian Development (CEDLA). The rapid expansion of illegal gold mining in the Amazon powers one of the country’s largest export industries. As global gold prices have increased, the industry is creating massive social and environmental challenges as well as severe health threats to indigenous communities.

This expansion is fuelled in part by generous fossil-fuel subsidies, which in turn finance the growth of the soy, cattle and mineral sector. According to 2021 data from the International Monetary Fund fossil-fuel subsidies consume 6,7% of Bolivia’s GDP. In addition, illegal settlements in the lowlands feed from these larger economic changes as communities transform forests into agricultural production lands through destructive slash-and-burn techniques, which increase wildfire risks.

How to save the Amazon

Regional collaboration to protect the Amazon took a serious hit during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. The announced revitalization of cooperation in the Amazon basin and surrounding forests through the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization offers a unique window of opportunity to end deforestation. But this opportunity will be wasted unless the following key issues are addressed.

-

Pan-continental regulation: It is no secret that countries that enforce strict forest-conservation laws tend to see the most ruthless industries emigrate to less-regulated countries; experts call this phenomenon “deforestation leakage”. To protect the Amazon in Brazil, the international community therefore has every interest in ensuring that Bolivia is not forgotten. World Bank data shows that Bolivia is a perfect destination for its neighbours’ predatory sectors, with much of the state’s regulation rolled back in the past 10 years.

To counter this, the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization should form a task force that directly addresses such cross-border leakage risks to protect the forests of the region, and the people who depend on them for their livelihoods. Lessons from studies of the effects of previous zero-deforestation policies] will offer useful guidance in these ambitions. Countries should ramp up their support for cross-border supply chain transparency, provide enough resources to enforce environmental legislation on the ground, and make sure indigenous rights are properly protected.

-

Phasing out forest-hungry policies and industries: The case of Bolivia also highlights a general challenge that countries in the region are facing: the need to not only “scale up” green financial innovations, but also actively phase out unsustainable economic activities, harmful subsidies and policies that increase inequality.

Don’t get us wrong: saying goodbye to industries like unchecked cattle ranching, and incentives such as fossil-fuel subsidies will take strong political will. But the world abounds with examples to draw inspiration from. Two include the Just Energy Transition Partnership that was concluded at the annual climate summit in Glasgow, COP26 and the international support to help decarbonize coal retirement in Indonesia. They show it is possible to move away from harmful industries while making sure local communities aren’t left behind.

-

Cleaning up the finance industry: In today’s globalized economy, large companies often rely on capital from financial institutions to conduct their operations. The financial sector has made progress in mobilizing its influence as owners and lenders to put pressure on industries associated with deforestation risks in the Brazilian Amazon. The sector must now mobilize to help protect the enlarged Bolivian Amazon.

Cascading negative changes resulting from deforestation, such as disrupted hydrological cycles, negative health impacts, and biodiversity loss will eventually impact negatively on investments. The financial sector thus needs to support national legislation and financial regulation that shift investments away from extractive economic practices that amplify social inequalities, toward new ways of protecting forests while simultaneously promoting education, health, sanitation, employment, and other development goals. Major initiatives like the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment, pension funds in the Global North, and international development banks must work closely with countries around the Amazon basin to make sure deforestation and climate ambitions are translated into action.

Bolivia’s forests, and the communities that depend on their resilience for their livelihoods, are facing a perfect deforestation storm. Swift national and international action is of the essence.

This article was co-written with Guido Meruvia Schween, a programme officer at the Swedish Embassy in La Paz, Bolivia.

Victor Galaz, Deputy Director and Associate Professor, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured Image: Deforestation in Santa Cruz, Bolivia (2021). Photo courtesy of Overview.

https://www.over-view.com/, CC BY-NC

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved