End Systematic Impunity for Unlawful Lethal Force

( Human Rights Watch ) – (Jerusalem) – The Israeli military and border police forces are killing Palestinian children with virtually no recourse for accountability.

Last year, 2022, was the deadliest year for Palestinian children in the West Bank in 15 years, and 2023 is on track to meet or exceed 2022 levels. Israeli forces had killed at least 34 Palestinian children in the West Bank as of August 22. Human Rights Watch investigated four fatal shootings of Palestinian children by Israeli forces between November 2022 and March 2023.

“Israeli forces are gunning down Palestinian children living under occupation with increasing frequency,” said Bill Van Esveld, associate children’s rights director at Human Rights Watch. “Unless Israel’s allies, particularly the United States, pressure Israel to change course, more Palestinian children will be killed.”

Human Rights Watch researchers, in documenting the four killings, interviewed in person seven witnesses, nine family members, and other residents, lawyers, doctors, staff and fieldworkers at Palestinian and Israeli rights groups, and reviewed CCTV and videos posted on social media, statements by Israeli security agencies, medical records, and news reports.

Human Rights Watch investigated the case of Mahmoud al-Sadi, 17, killed by Israeli forces as he walked to school near the Jenin refugee camp on November 21, 2022. The Israeli military did not address his killing specifically but said its forces had been conducting arrest raids in the camp, during which they exchanged fire with Palestinian fighters. However, the nearest exchange of fire occurred at one of the alleged fighter’s homes, about 320 meters away from where Mahmoud was shot, based on residents’ statements.

Mahmoud stood by the side of a road, waiting for the sounds of shooting in the distance to stop, and was not holding any weapon or projectile, a witness said and a security-camera video that Human Rights Watch reviewed showed. After the distant shooting had stopped and the Israeli forces were withdrawing, a single shot fired from an Israeli military vehicle roughly 100 meters away struck Mahmoud, the witness said. No Palestinian fighters were in the area, the witness said. Mahmoud was killed a block away from the street where Israeli forces killed the journalist Shireen Abu Aqla on May 11, 2022.

In the other cases investigated, the security forces killed boys after they had joined other youths confronting Israeli forces with stones, Molotov cocktails, or fireworks. While these projectiles can seriously injure or kill, in these cases, Israeli forces fired repeatedly at chest-level, hitting multiple children, and killed children in situations where they do not appear to have been posing a threat of grievous injury or death, which is the standard for the use of lethal force by law enforcement officers under international norms. That would make these killings unlawful.

Mohammed al-Sleem, 17, was shot in the back while running from Israeli soldiers after a group of friends he was with threw rocks, and allegedly Molotov cocktails, at military vehicles that had entered a village near his hometown of Azzun in the northern West Bank. Three other children were shot and wounded with automatic gunfire while running away.

An Israeli officer shot Wadea Abu Ramuz, 17, from behind while he was with a group of youths throwing rocks and launching fireworks at Border Police vehicles in East Jerusalem at around 10 p.m. on January 25, 2023, two witnesses said. Another boy in the group was shot and wounded. Security forces shackled Wadea to his hospital bed, beat and prevented his relatives from visiting him, withheld his body for months after he died, and required his family to bury him quietly at night.

In all cases, Israeli forces shot the children’s upper bodies, without, according to witnesses, issuing warnings or using common, less-lethal measures such as tear gas, concussion grenades, or rubber-coated bullets. Adam Ayyad, 15, was fatally shot from behind in Deheisheh refugee camp on January 3 while with a group of boys throwing stones and at least one Molotov cocktail at Israeli forces. The soldier also shot and wounded a 13-year-old boy, witnesses said.

The Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported in January that since “December 2021, soldiers are allowed to shoot at Palestinians who are fleeing if they had previously thrown stones or Molotov cocktails.” Human Rights Watch wrote to the Israeli military and police on August 7 with questions about the four cases and the forces’ rules of engagement. The police responded, but the military did not . The police rules of engagement permit the use of firearms against persons who are throwing stones, Molotov cocktails or fireworks only if there is an “imminent risk to life or bodily integrity.” The police also stated that they could not provide information about the case of Wadea Abu Ramuz because it was under investigation.

Israeli authorities have used excessive force against Palestinians in policing situations for decades. The authorities have routinely failed to hold their forces accountable when security forces kill Palestinians, including children, in circumstances in which the use of lethal force was not justified under international norms. From 2017 to 2021, fewer than one percent of complaints of violations by Israeli military forces against Palestinians, including killings and other abuses, resulted in indictments, the Israeli rights group Yesh Din reported.

Israeli forces killed at least 614 Palestinians whom the UN classified as civilians in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank during this period. But only three soldiers were convicted for killing Palestinians, according to Yesh Din, and all received short sentences of military community service. The Israeli rights group B’Tselem, which for decades filed documented complaints about killings to the Israeli military, has deemed the Israeli law enforcement system a “whitewash mechanism.” In 2021, out of 4,401 complaints to the department of internal police investigations, which include complaints by Israeli citizens, just 1.2 percent resulted in indictments, according to the state comptroller.

The killings take place in a context in which Israeli authorities are committing the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution against Palestinians, including children, as Human Rights Watch and other rights groups have documented. The then International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, opened a formal investigation in 2021 into serious crimes committed in Palestine.

The UN Secretary-General is mandated by the Security Council to annually list military forces and armed groups responsible for grave violations against children in armed conflict. Between 2015 and 2022, the UN attributed over 8,700 child casualties to Israeli forces, yet Israel has never been listed. The reports have repeatedly listed other forces that killed and injured far fewer children than Israel did.

The stigma attached to the Secretary-General’s “list of shame” is considerable, and parties named must create and carry out an action plan of reforms to end the abuses in order to be removed from the list. The UN missed an opportunity to protect children by omitting Israel, Human Rights Watch said. The Secretary-General should use objective criteria to determine the list for 2023.

“Palestinian children live a reality of apartheid and structural violence, where they could be gunned down at any time without any serious prospect of accountability,” Van Esveld said. “Israel’s allies should confront this ugly reality and create real pressure for accountability.”

Mahmoud al-Sadi, Jenin refugee camp

Israeli forces killed Mahmoud al-Sadi, 17, while he was walking to school in Wadi Burqin, near the Jenin refugee camp, at around 9:30 a.m. on November 21, 2022. The Israeli military did not address or announce any intention to investigate Mahmoud’s killing, but said its forces were conducting arrest raids and exchanged fire with Palestinian fighters. There were no reports that Israeli troops were injured.

The exchanges of fire occurred when Israeli forces surrounded the family homes of two alleged fighters, and the nearest home was about 320 meters from where Mahmoud was shot. Residents identified the building to Human Rights Watch, and videos posted on social media show fighting at the same building.

Mahmoud had dropped off his sisters, ages 8 and 10, at their elementary school and was walking to his secondary school with other students, when “all of a sudden there’s [the sounds of] shooting in the distance, we didn’t know where, and people say the [Israeli] military is present,” said a classmate who was walking with Mahmoud. Mahmoud waited for safety on the side of a street. A security-camera video, which Human Rights Watch viewed, showed him wearing his school backpack, standing alone, and not holding any weapon or rock, just before he took a step into the street and was shot, his father and the classmate said.

The shooting in the distance had stopped and the military was withdrawing when Mahmoud’s classmate said he heard a gunshot. Mahmoud stepped toward him, said he had been hit, and fell down. The witness and other boys saw a stationary Israeli military vehicle roughly 100 meters up the street, which then drove away. Human Rights Watch visited the site and found that if the shooter had been in this vehicle, they would have had a clear view of Mahmoud. A medical intake report for Mahmoud from Ibn Sina Hospital in Jenin at 9:50 a.m. records a single bullet wound and hemorrhagic shock.

No armed Palestinians or other Israeli forces were in the area at the time, said the classmate and reports by news media and rights groups, raising concerns that the Israeli forces may have deliberately targeted him even though he was unarmed and not engaging in violent activity. The intentional or reckless use of lethal force against a person who poses no imminent threat to life by the security forces of an occupying power carrying out policing operations would be unlawful. The “willful killing” of members of the population of an occupied territory is a war crime.

After the killing, the Israeli military cancelled Mahmoud’s father’s permit to enter Israel, where he worked. It took three months and 8,000 NIS (US$2,200) in lawyers’ fees to obtain a new permit, Mahmoud’s father told Human Rights Watch. The Israeli military views relatives as aggrieved “potential avengers” and automatically cancels their work permits as a security measure, harming them through a blanket policy that offers no meaningful individual assessments.

Wadea Abu Ramuz, East Jerusalem

At around 10 p.m. on January 25, 2023, an Israeli officer shot Wadea Abu Ramouz, 17, in the back as he was with a group of youths who were throwing stones and launching fireworks at Border Police vehicles on the main street in the Ein el-Lowzeh area of Silwan, a neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem, two witnesses said. Human Rights Watch visited the site where the youths had gathered, on a hillside about 30 meters from where the Border Police vehicles were passing below on the neighborhood’s main street.

The witnesses did not see whether Wadea had launched fireworks or threw stones. The officer who shot Wadea was positioned further up the hillside behind them, a witness said. A second child was also shot and subsequently released from the hospital. His family declined to speak with Human Rights Watch.

Israeli medics provided first aid and took Wadea to Shaarei Tzedek hospital in West Jerusalem. No Israeli authority informed Wadea’s family of where he had been taken, relatives told Human Rights Watch. The family called the Israeli emergency service, the police, and visited two hospitals before going to Shaarei Tzedek, where Palestinian hospital staff informally told the family that a “critical case” whom they suspected was Wadea, had been admitted.

Blocked by the police from entering, the family “stayed in the parking lot all night,” a relative said. At 4:30 a.m., “as a favor to us, [a hospital staff member] sneaked an article of [Wadea’s] clothing to the front gate, to let us confirm that it was him.”

Israeli police at the hospital refused to allow Wadea’s parents to see him on the basis that he was a “detained criminal suspect,” until lawyers obtained a court order for a family visit the next afternoon. Police had shackled Wadea to the hospital bed, hand and foot, though his father and lawyer said he was unconscious and connected to multiple medical devices.

On January 27, other relatives were waiting to visit him in the hospital parking lot when police said they had to leave, forced one man to the ground and beat him and pushed the group out of the lot, family members said.

At around 9:30 p.m., Palestinian journalists called Wadea’s lawyer to ask about rumors of his death. A security official at the hospital told him to wait outside and returned at 12:10 a.m. with Wadea’s death certificate, the lawyer said.

At 8:00 a.m. the next day, Border Police raided the family’s yard, broke down the condolence tent, confiscated Palestinian flags and posters of Wadea, and broke plastic chairs, a relative said. Border Police returned several times in the following days and forcibly dispersed neighborhood residents who “kept coming to our home, spontaneously … waiting and expecting the body to be released. There were confrontations and they fired tear gas.”

Israeli authorities took Wadea’s body for autopsy. The Israel Security Agency (known as the Shabak, or Shin Bet), which Israeli law grants authority over the return of bodies of Palestinians killed by Israeli forces in what they consider security incidents, then refused to return the boy’s body to his family. Israeli authorities currently hold in morgues the bodies of at least 115 Palestinians, including 15 children, killed in what the authorities consider security operations. The family’s lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court, which upheld their demand on May 4, but without specifying a date.

The family received the body from Israeli police at 10 p.m. on May 30 near the entrance to a cemetery, after paying a 10,000 NIS (about $2,725) guarantee that would be forfeited unless they conducted the burial immediately, admitted at most 25 mourners, and did not take photographs, chant, or raise Palestinian flags, said the lawyer, who was present. Police checked the mourners’ identification documents and kept them, and the mourners’ mobile phones, during the burial.

The lawyers also appealed to the Department of Internal Police Investigations within the Office of Israel’s State Attorney (“Machash”), to investigate Wadea’s shooting, but had not received updates regarding their complaint by mid-August.

Wadea’s father was fired from his job at an Orthodox Jewish institution in Jerusalem when the management learned his son had been shot, he said. Border Police also took the principal of Wadea’s school, Shatha Mahmoud, from her school for questioning about a Facebook post in which she criticized his killing, said residents and the Wadi Hilweh Information Center, a local organization that documents rights abuses.

Mohammed al-Sleem, Azzun

On the evening of March 2, Mohammed al-Sleem, 17, and a group of five friends he had grown up with were walking from the town of Azzun to the nearby village of Izbat al-Tabib, where a relative had a home at which the group regularly “hung out,” one boy said. Azzun is close to Road 55, which connects the large Israeli settlements of Alfei Menashe and Karnei Shomron.

Human Rights Watch spoke to two of Mohammed’s friends, ages 16 and 17, who were with him at the time, and three of his relatives. At around 7:40 p.m., the boys saw a dark blue Israeli truck with military license plates on the road that runs through the village, they said. According to reports by local media, based on residents’ accounts, the youths threw rocks or Molotov cocktails at the vehicle, which was roughly 30 meters away. The boys said the military vehicle had protective metal mesh over the windows, which could significantly reduce the risk of serious injury or death. A second military vehicle arrived next to the first, and the boys ran in different directions as four soldiers got out of the vehicle and fired assault rifles at them. The two witnesses said they heard between two to five individual gunshots followed by automatic gunfire.

Mohammed ran down a side street past an elementary school about 80 meters from the village road, and through plots of land with olive trees, his friends said. His friend, age 16, recalled, “We started running, and Mohamed told me, ‘I’m hit’, and I said, ‘Run! Run!’ and I was shot too. I ran about 100 meters, then I couldn’t go on.” A bullet pierced the back of the left shoulder of Mohammed’s friend and exited his chest. He collapsed but was able to call for help from relatives in the area, he said. He said that he cannot lift his left arm, or take deep breaths because of his injuries.

Mohammed was shot in the back by a bullet that lodged in his right lung. He ran approximately 200 meters, then collapsed in a field. Residents reached him 30 minutes later, found him unconscious, and took him to a hospital in Azzun in a private vehicle. He was transferred by ambulance to a hospital in the Palestinian city of Qalqilya and pronounced dead on arrival.

A third boy, 17, was shot through the bicep, he said, and a fourth, 16, had a superficial wound from a bullet that grazed his lower back. Researchers counted 10 apparent bullet impacts on the wall of the schoolyard, and others in olive trees, consistent with witness descriptions, indicating that Israeli soldiers fired a significant number of high-velocity assault-rifle rounds at fleeing children at a time when they posed no threat to life or of causing injury.

The military reported on the incident and said “hits [of Palestinian suspects] were identified” but did not report any injuries to soldiers.

Israeli forces regularly raid Azzun, residents said. They perceived the raids as a disproportionate, a collective deterrent against throwing rocks at Israeli vehicles driving to and from the settlements on Road 55, recalling repeated warnings by Israeli officers in the area against throwing stones at the road. On April 8, a soldier in a military vehicle fatally shot Ayed Sleem, 20, in the chest, although he was not armed or throwing projectiles at the time, an Israeli news report said.

Adam Ayyad, Deheisheh refugee camp

A large Israeli force was withdrawing after a raid on Deheisheh refugee camp near Bethlehem at around 5:00 or 5:30 a.m. on January 3, when Adam Ayyad, 15, joined a group of youths who threw stones at Israeli forces on a street below them, three boys who were there at the time said. After another boy threw a Molotov cocktail, an Israeli soldier in a building overlooking the street where the boys were, fired repeatedly at the group, two of the boys said.

The Israeli military told news media in general terms that Border Police officers had shot suspects during the large-scale raid on the camp, in response to Molotov cocktails, explosive devices, and stones thrown at them, but did not address Adam’s killing specifically.

The witnesses said that one bullet went through the window of a parked car and then wounded a 13-year-old. The soldier fired again repeatedly and hit Adam. A Palestinian Medical Relief Society medic who lives in the area said that repeated gunfire from Israeli forces delayed him as he tried to reach the wounded boys to stop their bleeding.

Human Rights Watch could not determine whether Adam was holding a projectile at the time. However, the three boys said that the members of the group began running away as soon as they heard the first shot. Several news reports cited an initial statement from the Palestinian Health Ministry that Adam was shot in the chest, but doctors at the hospital where Adam was taken and pronounced dead told Human Rights Watch that his wounds indicated the bullet hit him in the right side of his upper back and caused a large wound in the front of his chest, indicating that he had turned away from the direction of the Israeli soldiers and the shooter. Defense for Children International – Palestine also reported that Adam was shot in the back.

Based on witness statements, the Israeli forces were withdrawing roughly 45 meters away on the street below, and could have been hit by projectiles thrown from the youths’ more elevated position. The shooter was apparently in a room on the unfinished top floor of a multi-story building 73 meters away, where the boys later found spent bullet casings. That is consistent with Human Rights Watch researchers’ observations of bullet impacts at the site.

The shooter was apparently in position before the boys began throwing projectiles, but Israeli forces did not issue a warning, use less-lethal weapons, or shoot at the boys’ extremities before the shooter repeatedly fired with live ammunition at the group, with the bullets striking at chest-level, the witnesses said.

The incident raises questions about whether the shooter had targeted members of the group who posed an imminent threat to life or of serious injury, and if so, whether the shooting continued beyond the point where it could be deemed necessary. The military did not report any injuries to their forces during the raid.

Adam, an only child, had stopped attending school and found work in a bakery from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. each day, a coworker said, to help support his mother, who is divorced and was raising him alone. Israeli forces had killed a friend who worked at another bakery nearby, Omar Manah, 23, during a raid on December 5, a relative said, and Adam was carrying a handwritten statement meant to be read if he was killed, which read, in part, “I had a lot of dreams I wished would come true but we are living in a reality that makes your dreams impossible.” His mother sometimes still prepares meals for both of them, especially his favorite dishes, she said.

International Law on Use of Force and Israeli Investigative Practices

International human rights standards prohibit law enforcement officials from “the intentional lethal use of firearms” except when “strictly unavoidable to protect life.” Throwing rocks, Molotov cocktails, and explosive fireworks could pose a risk to life, depending on the circumstances. However, nonviolent means and warnings must be used first whenever feasible, and force may be used “only if other measures to address a genuine threat have proved ineffective or have no likelihood of achieving the intended result.” The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials provides that, “Every effort should be made to exclude the use of firearms, especially against children.”

Palestinians in the West Bank are protected under the Geneva Conventions. Willful killings of protected persons by the occupying power outside what is permissible under human rights standards would constitute a grave breach of the laws of occupation.

Under international human rights law, governments “must ensure that individuals also have accessible and effective remedies to vindicate” their rights, including the right to life.

The Israeli military does not automatically open criminal investigations into cases in which soldiers use lethal force against Palestinians in the West Bank, including if a complaint is filed. Human Rights Watch has found that investigations are more likely to be opened in cases in which international news media report extensively on the killing. The armed forces military police carry out investigations and, regardless of whether an investigation is opened, impunity remains the norm.

Recommendations

- The Israeli military and Border Police should end the unlawful use of lethal force against Palestinians, including children. The Israeli government should issue clear directives publicly and privately to all security forces, that prohibit the intentional use of lethal force except in situations where it is necessary to prevent an imminent threat to life.

- The United Nations Secretary-General should list Israel’s armed forces in his annual report on grave violations against children in armed conflict for 2023 as responsible for the violation of killing and maiming Palestinian children.

- The prosecutor of the International Criminal Court should expedite his office’s Palestine investigation, including for grave violations committed against children.

- Foreign governments, such as the US which pledged $3.8 billion in military aid to Israel in 2023, should condition assistance on Israel taking concrete and verifiable steps toward ending their serious abuses, including the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution and the regular use of lethal force against Palestinians, including children, that violate international standards, and to investigate past abuses. It should suspend assistance so long as these grave abuses persist.

- Members of the US House of Representatives should support the Defending the Human Rights of Palestinian Children and Families Living Under Israeli Occupation Act (H.R. 2590), which would prohibit US funding to Israel from being unlawfully used for the military detention and abuse of Palestinian children, destruction of Palestinian property, and expropriation of land for settlements.

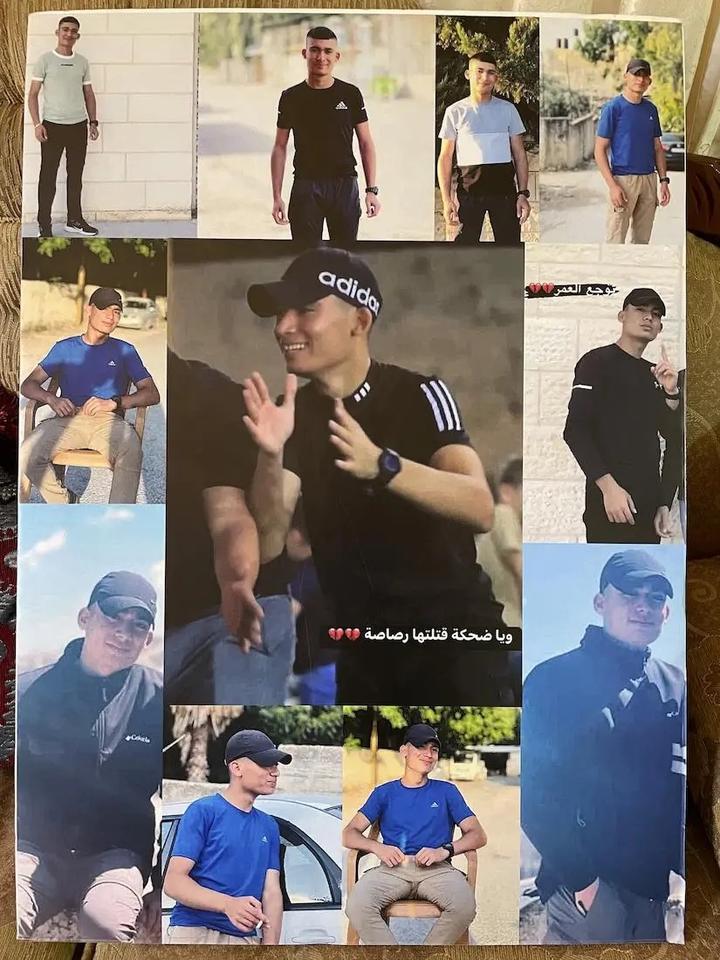

Featured Photo: Left to Right, Adam Ayyad, Wadea Abu Ramuz, Mahmoud al-Sadi, and Mohammed al-Sleem. © Private

Via ( Human Rights Watch

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved