Review of Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Heroes to Hostages America and Iran, 1800–1988 (Cambridge U.P., 2023)

“A Westerner in Iran inevitably misunderstands the country to some degree; his past and present are too different from those of the Iranian. ‘A foreigner may live here a hundred years, but he will never really understand us.’ An old Iranian once said to me. And by then I knew enough to know that he was right.”

– Terence O’Donnell, The Garden of Brave in War, Recollections of Iran”

When the subject of Iran and America comes to mind, two eventful episodes are often invoked by Iranians and Americans. The first is the CIA-led coup d’état of 1953, which toppled Mohammad Mossadegh’s democratically elected government; and the second is the taking of American hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran after the 1979 revolution.

On more than one occasion, U.S. presidents and diplomats have apologized to Iran for America’s interference in the country, yet the Islamic Republic has never taken responsibility for keeping American diplomats and personnel for 444 days in captivity.

Both these two events have left a lasting scar on the history of relations between the two countries.

But things are not that simple. Relations weren’t always contentious.

There was a time when America and Iran had in fact a good relationship and we are not referring to the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

The history of the relations between the two nations goes back to the early nineteenth century, as it is presented in a new book called Heroes to Hostages: America and Iran, 1800-1988 published by Cambridge University Press, 2023, and authored by Dr. Firouzeh Kashani Sabet, the Walter Annenberg Professor of history at U. Penn and the newly elected President of the Society of Iranian Studies.

This informative, well written and well researched work takes us back to the 1830’s, to the first encounter between the two nations. It was an amicable relationship, mostly involving the work of American Presbyterian missionaries in Iran. It was to benefit both people.

Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Heroes to Hostages America and Iran, 1800–1988. Click Here.

There was no oil, there were no coups, no White Revolution, no arms sales, no military advisors, no Kennedy or Nixon doctrines and no hostage taking. Unlike Iranians’ history of suspicion towards the British, they did not share the same view towards America or Americans’ role in Iran until 1953.

Instead, there were missionaries, Perkins, Graham Wilson, Howard Baskerville, Morgan Shuster, and the Peace Corps.

In 1833, the first missionary, the Reverend Justin Perkins, set foot in Iran and spent some 8 years in the country preaching to about 140,000 Nestorian Christianss. He noted, “No American was ever a resident of that ancient and celebrated country before me” (page 17). Among other things he did, was using a printing press in Urumiyeh, in northern Iran to make the Scriptures available to all. In an act of compassion, from Ohio, contributions were sent to Iran to alleviate the suffering of famine victims in Iran. The missionaries were also involved in other work, including the establishment of schools and medical centers in Hamadan, Tabriz and Tehran.

Although in most cases, the missionaries were left alone by the local government, as many of the officials’ sons were also being educated there, there were instances when governors forbade the participation of Muslims as was the case of classes held by a Reverend A. R. Blankett.

In an unfortunate incident, a missionary by the name of Benjamin Woods Labaree was killed by Kurdish bandits. His murderer was later found and sentenced to life in prison.

Of course, the name Howard Conklin Baskerville is no stranger to Iranians. He was a missionary who decided to join the nationalists after the Constitutional Revolution of 1906. As a young man, he fought alongside them and died at the age of twenty- four on April 19, 1909.

He is buried in Tabriz where his tomb is visited by many Iranians and tourists. Before he died, he had declared, “I am Persia’s.” (page 74)

Another well-known American was William Morgan Shuster, a banker from New York, who in 1911, was engaged by the Iranian government to put the country’s fiscal house in order. Even though he was at times frustrated with the authorities, he applauds the Iranians for their sacrifices in trying “to change despotism into democracy.”

In his well-known book, The Strangling of Persia, he wrote: “It was obvious that the people of Persia deserve much better than what they are getting, that they wanted us to succeed, but it was the British and the Russians who were determined not to let us succeed.”

An American Society was formed in 1925 to promote commerce and exchange in art and literature between the two nations. Among the historians who visited Iran was Arthur Upham Pope (he is buried with his wife along the Zayandeh Rud in Isfahan) who gave a talk about Persian art with Reza Shah being in attendance. At the same time, in 1926, a statesman, Seyed HasanTaghizadeh had been Iran’s representative in Philadelphia exposition and spent time in America.

In early 1936, a Thomas R. Gibson came to Iran to direct the Iranian scouting program. Reza Shah who had crowned himself as the first king of the Pahlavi dynasty, having rapid modernization in mind, embarked on the forced unveiling of Iranian women. An American minister to Iran, William Hornibrook had deducted that Reza Shah’s top-down secular reforms, had alienated many Iranians, especially the clergy. (page 121)

In her comment to me, Dr. Kashani Sabet says: “I think the social work was important, yes. When missionaries provided medical support to the poor, especially poor women it was valuable. The peace corps also stepped in during the 1968 earthquake. These types of interventions and support ] were helpful. Unfortunately, the broader context of Western and US imperialism and later the Cold War were framing this involvement and relationship, which politicized it and made it easy to erase any good that might have come from it.”

The name Samuel Jordan who became the director of the famous Alborz college, established previously in 1873, comes to mind. (Alborz was later re- named the American College). Many others Americans become instrumental in creating good will, including the dozens of Peace Corps volunteers, some of whom fell in love with the country and its culture and later upon returning, become major academics of Iran. Among them was Ambassador John Limbert who became a hostage for 444 days.

Other Americans or American actions in Iran leave a sour taste:

Personalities like general Norman Schwarzkopf Sr., the man who assisted with the organization of the Iranian gendarmerie (father of the famous son and commander of the coalition forces in Operation Desert Storm) and then Kermit Roosevelt, Donald Wilbur (both involved in the coup) and Richard Helms ( the ex-CIA chief and later U.S.ambassador to Iran).

The book examines the CIA/MI6 coup like so many other books have covered. Suffice to say, that Dr Kashani Sabet examines this event like all academics as a turning point in the negative way which affected the relationship between the two nation .

The coup d’etat toppling a beloved Prime Minister and his government left a lasting mark on the Iranian psyche.

On November 15, 1953, Vice President Nixon representing Eisenhower, whose administration was complicit in the 1953 Coup, comes to Iran to pay tribute to the Shah. On December 9 of that same year, massive protests take place at Tehran University were three students are killed.

The law of capitulation was one that both Dr. Mossadegh and the clergy objected to which gave amnesty to Americans who committed crimes in Iran. In 1964, the Iranian parliament ratified a law giving immunity to members of the military missions and their dependents. This unfair law was one of the first which was dismantled by the revolutionary government in 1979.

In the 1960’s and 70’s, the Shah, whose reign was always shadowed by a coup, purchases vast number of arms, including F 16’s, and AWACKS.

He becomes the gendarme of the region.

Western influence including a sexual revolution takes place.

Discos and miniskirts take root in a very religious society. The Shah and his entourage are pro-American. Iranian cinema except on seldom cases showed semi-nude women. SAVAK whose creation is aided by the CIA starts as an intelligence apparatus but later becomes a tool of torture of dissidents including leftists and religious elements.

Ali Shariati, the famous Iranian sociologist writes, why should we not know about someone like Angela Davis but instead we must be aware of Miss Twiggy! (Page 327)

In between the years, a lot of investments are made by U.S. companies and other western companies. Some helped develop the country but mainly it was intended to make Iran into a client state.

But how much any of these developments and modernization help the Shah and his regime sustain its rule? Perhaps they did superficially but on a deeper level they did not.

The 1978-1979 events in fact shattered the illusion of the “Island of peace and stability.”

The 1979 revolution was blamed on Jimmy Carter since most Iranians do blame foreigners for their fate. Was it right? Not by any factual account. Not always.

Gary Sick, the national security advisor to President Carter, said in an interview that there was no reason the President wanted to rid of the Shah. He was our ally, and he protected our interests. Carter was busy with the Camp David accord and thus the news coming from Iran was not alerting to him as both his Ambassador (Sullivan) and the Shah himself had assured the U.S. administration that all things were in control.

Well, they were not. The Shah was too sick and he had hidden his fatal illness to everyone. The CIA had no knowledge of it.

The Shah could not make the right decisions in the most turbulent period. He asked General Huyser for advice. His Iranian advisors were also incompetent. Alam, his court jester, had died.

And then the hostage take-over takes place which completely put Iran and America at odds.

The rest is history as we say.

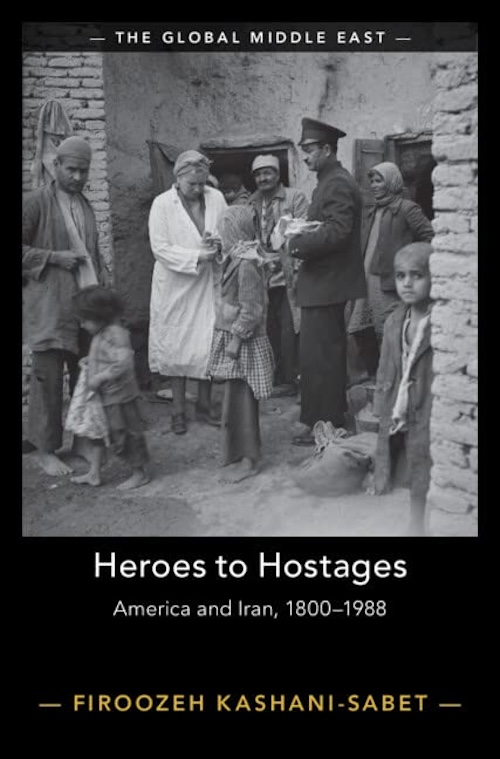

The cover of this book is a 1943 photo of Mrs. Louis Dreyfus, the wife of the U.S. minister to Iran giving food to Iranian children.

There are other interesting illustrations, among them, the Fiske seminary students (women) in 1900, Angela Davis in Zaneh Rouz, (woman of today), various comic drawings in the famous Towfigh satirical monthly illustrating the Roger Plan and a photo of demonstrations holding banners of “Yankee Go Home”. ( page 203)

The image of three girl scouts with their short hair in 1936 is noticeable, a far cry from the images of forced veiled women after 1980.

This book, unlike other books on this very subject, is not only elegantly written, but draws the reader to a more intense and detailed history of the U.S./ Iran relations, many aspects of which remain little known to us.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved