As much of the Great Lakes region experiences its warmest winter on record, and more record high temperatures are expected in Michigan, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has reported record low levels of ice coverage on the Great Lakes, amid a steady, decades-long decrease in coverage.

Lake Michigan in Chicago, March 1, 2024 | Susan J. Demas

While ice coverage on the Great Lakes usually peaks in the late February to early March, NOAA began reporting daily record-lows for Great Lakes ice coverage on Feb. 8, through Feb. 15. While there was a brief spike above historic lows after Feb. 15, those numbers quickly neared and tied low ice-coverage records, with historical lows recorded on Feb. 27 and 28, Jennifer Day, director of communications for NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory said in an email.

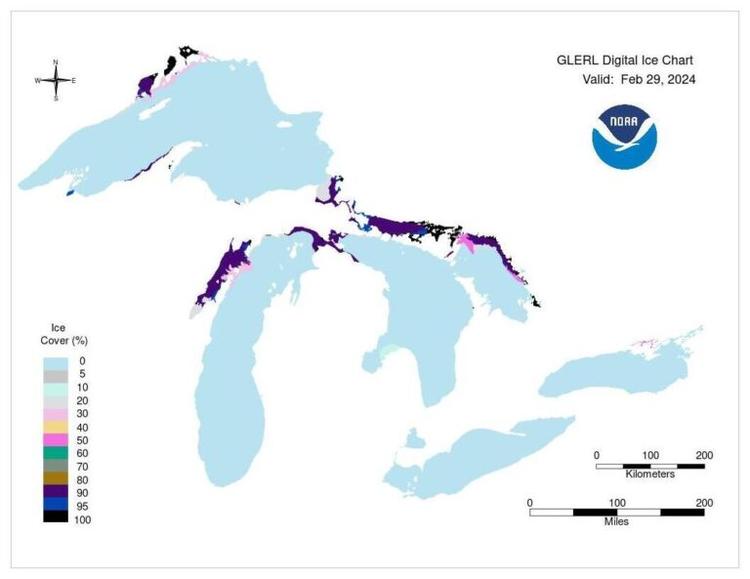

Ice coverage on the individual lakes has followed similar patterns, with Lake Superior, Lake Michigan and Lake Huron recording historic low coverage for the date on Feb. 28, while ice concentration for Lake Erie sat at 0% and concentration on Lake Ontario sat at less than half a percent.

NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory Ice Coverage Chart for Feb. 29, 2024. | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Ice concentration on Lake Superior sat at 1.74% on Wednesday, while NOAA recorded 3.6% concentration in Lake Michigan and 7.84% concentration in Lake Huron.

The total peak for ice concentration across the five lakes was recorded on Jan. 22, with 16% coverage. However, Lake Superior has since recorded a new maximum for the year on Feb.19, exceeding its January peak.

Ayumi Fujisaki-Manome, an associate researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research told the Michigan Advance the lack of ice is the result of anomaly conditions overlaid on long term warming trends. Alongside El Niño conditions contributing to a warmer and wetter winter than normal, the North Atlantic Oscillation — which describes atmospheric pressure patterns — is in a positive phase, which prevents cold arctic air from coming down into the Great Lakes region.

Day noted that the strong El Niño coupled with a warm December and above average air and water temperatures throughout winter did not create the conditions needed for ice to develop.

Low ice was also recorded in 2020 and 2023, Day said, with the annual maximum coverage near 20%, compared to the long-term average of 53%.

However, NOAA has also recorded very high ice years in the previous decade, in 2014, 2015 and 2019.

“Even though there’s a decreasing trend in max ice (5%/decade), there is a great deal of year to year variability,” Day said.

Although there has been a long-term decline in Great Lakes Ice Coverage, predicting those fluctuations from year to year remains a big question for researchers, Fujisaki-Manome said.

While a lack of ice may bring disappointment for those looking to ice fish in the Great Lakes, or visit ice caves near the coast, the lack of ice coverage also carries concerns for shoreline conditions, lake effect weather, and for various animal species in and around the Great Lakes.

Ice coverage serves as a barrier, protecting coastlines from high winds, high waves and storm surges. Without that barrier there will be long-term impacts, such as shoreline erosion, Fujisaki-Manome said.

A lack of ice to protect from waves makes shorelines more susceptible to coastal flooding and creates a higher potential for storm damage to shoreline infrastructure, Day said.

Additionally, less ice and more open water is the perfect set up for a lake effect snowstorm or an ice storm, Fujisaki-Manome said.

During late fall and winter cold air flowing over the warm waters of the Great Lakes leads to the production of lake effect snow leading to increased snowfall in areas downwind from the lakes. This effect usually diminishes late into the winter season, as the formation of lake ice reduces the supply of warm and moist air in the atmosphere.

Thick, stable ice also protects fish eggs that are deposited nearshore in the fall and incubate over winter, Day said. Ice cover can help minimize the effect of waves that would dislodge or break apart eggs from species like lake whitefish or lake herring, she said.

Ice cover also affects winter fishery harvests, especially in bays, drowned river mouth lakes and nearshore areas, Day said. During cold winters when ice is thick and lasts three to four months, harvests for panfish, whitefish, bass, walleye and yellow perch are high, with low harvests when coverage is low and unstable.

It is unlikely that total ice coverage across the Great Lakes will exceed its January peak, Day said.

Significant ice growth is not expected over the coming weeks, and longer term temperature trend predictions indicate that ice levels across the Great Lakes will likely remain below average for the next several weeks, Day said.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved