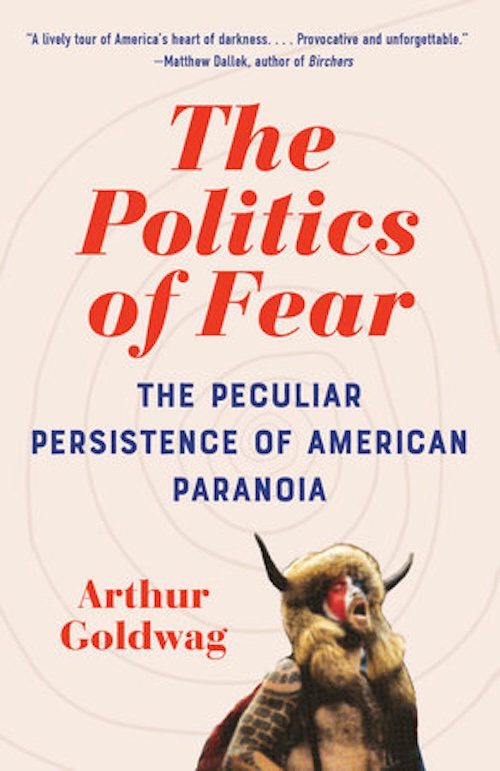

Brooklyn, NY (Special to Informed Comment; featured) – The cover of my The Politics of Fear: The Peculiar Persistence of American Paranoia features a photograph of a bearded, fur-clad man with a horned helmet, tattoos and face paint. On January 6, 2021, Jacob Anthony Chansley, aka the Q Shaman, stood at the House Speakers’ dais in the US Capitol building and led a prayer, in which he thanked the “divine, omniscient, omnipotent creator God” for allowing his fellow patriots and him “to send a message to all the tyrants, the communists and the globalists that this is our nation, not theirs.”

Chansley has written two books and produced a dozen or so videos about his political ideas; in October, 2023 he filed paperwork to run for Congress in Arizona’s Eighth District. Though he didn’t follow through and mount an actual campaign, had he run and won he likely wouldn’t have been the most extreme member of the House. And Donald Trump, whom Chanley and his fellow Q travelers believed was God’s anointed, is very much a contender for the highest office in the land.

Chansley’s red-pill moment came, he says, when he discovered the writings of the arch conspiracy theorist Milton William Cooper, who was inspired in his turn by The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the notorious forgery that purported to expose an ancient Jewish plot to destroy the Christian nations. As Chansley’s thinking evolved, he went on to embrace eco-fascism, anti-vax activism, Christian nationalism, New Age religiosity, and Libertarianism—a stew that is sometimes called “conspirituality.” I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words about the deep roots of paranoid conspiracy theory in American history, but if you want to know what they come down to, his prayer sums it up succinctly. It’s about how “they” are taking what is rightfully “ours.”

Who “they” are has changed over the centuries, but what’s “ours” has always been the privileges that white Christian men believed was their birthright, but for too many, seemed to be slipping away. In colonial times, “they” were agents of the Pope. In the 1790s and the 1820s they were atheistic members of the Illuminati and the Masons. By the mid-19th century, the enemy was the Irish and other Catholic immigrants who were competing for jobs. The fight over slavery spawned a host of rival conspiracy theories. During the post-Civil War era, which saw the failure of Reconstruction and the rise of vast economic inequalities, the focus shifted to English and Jewish bankers and the demonetization of silver. A few decades later, Jewish anarchists and reds and integrationists were also in the crosshairs. QAnon, the first conspiracy theory to be born on social media, takes bits and pieces from its predecessors, mixes and matches them with medieval blood libels and Gnostic apocalypticism, and gamifies it all by inviting believers to participate in its world-building. Donald Trump, in their telling, is secretly battling the elite cabal of pedophile cannibals who control the Deep State.

Whether they make you laugh or cry, those theories wouldn’t be as viral and sticky as they are if their believers weren’t experiencing real stresses—and if the horrible things they accuse their enemies of doing, everything from cannibalism to pedophilia and mass murder, weren’t behaviors that really do exist. Of course, Jews as a category don’t ritually torture and murder Christian babies, but human babies of all varieties—including Jewish ones—have been horrifically abused. More than 13,000 children have been killed by a largely Jewish army in Gaza in just the last several months.

And is it altogether delusional to imagine, as QAnon believers do, that elites get away with child abuse? The Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor might not have had a sex dungeon, as the proponents of the Pizzagate theory claimed, but Jeffrey Epstein certainly kept a harem of underaged women and had a circle of socially and politically connected friends that included billionaires, geniuses, and royalty. Epstein’s story—everything from the mysterious sources of his wealth to his odd connection to Trump’s attorney general (William Barr’s father was the headmaster of the Dalton School when it hired him as a teacher in 1974), and his mysterious suicide in jail in 2019—could have leaped fully formed from the head of an antisemitic conspiracy theorist, like Athena from the head of Zeus, but it was all true.

Trump’s voters’ feelings of dispossession are not that far off the mark either, as a host of not-so-fun facts about economic inequality make clear. A 2017 study found that the richest three Americans (none of them Jewish) controlled more wealth than the bottom 50 percent of the nation. The total real wealth held by the richest families in the United States tripled between 1989 and 2019, according to a 2022 Congressional Budget Office report, while average earners’ gains were negligible. The ten richest people in the world, nine of them Americans, doubled their wealth during the pandemic.

Our great national myth—that America is a crucible of equality, tolerance, and boundless economic opportunity—has never been our national reality. Though right-wing populism sees the world through a lens that is distorted by irrational hatreds, it nonetheless lands on a painful truth: that unregulated capitalism is brutal and unfair. Right wing conspiracists displace the blame for its crimes onto outsiders; progressives recognize that for all its very real gestures towards equity, justice, and universal opportunity, our constitutional order was erected on a rickety scaffolding of race supremacism, religious bigotry, involuntary servitude, and land theft and compromised by them from the very beginning.

Trump’s white male voters’ intuition that the system is rigged against them is more-or-less correct, even if the privileges their fathers were born to were undeserved, and their prescriptions to rejigger the fix in their favor could not be more pernicious. The fact that so many economic left-behinds look to Trump as their champion may be perplexing, but no one can doubt that they need one.

Whether Trump wins or loses this fall, the challenge for the center, the left, and even fair-minded members of the moderate right, is to create a reality-based narrative that can compete with Trump’s and Chansley’s—and that has reparation rather than retribution at its core.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved