Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – When a baby born on April 1, 2023 reached 14 months and became a toddler this month, it had never lived through a month that wasn’t the hottest on record.

The National Atmospheric and Oceanic Agency has announced that May 2024 was the hottest May on record. But even more worrisome, it was the 14th consecutive hottest month on record.

Records began being kept around 1850, when enough people around the world began noting down temperatures using a mercury thermometer. In fact, scientific proxies for temperatures before that date suggest we are now seeing averages that are the hottest in 125,000 years.

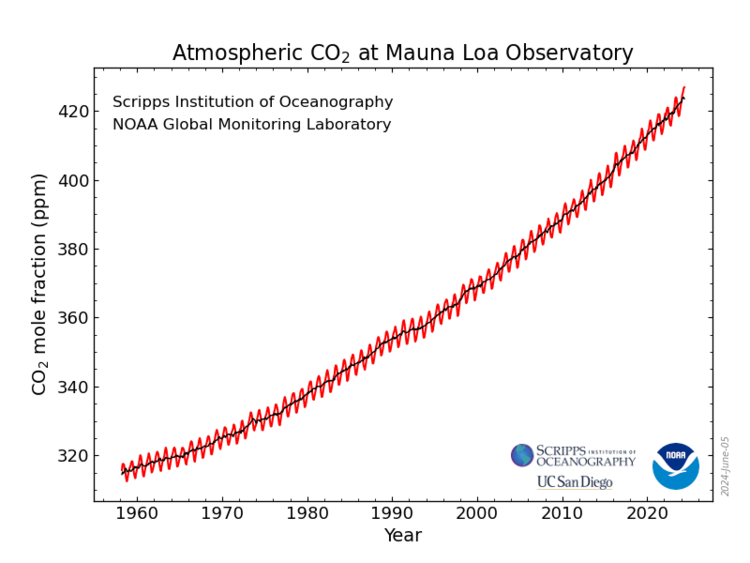

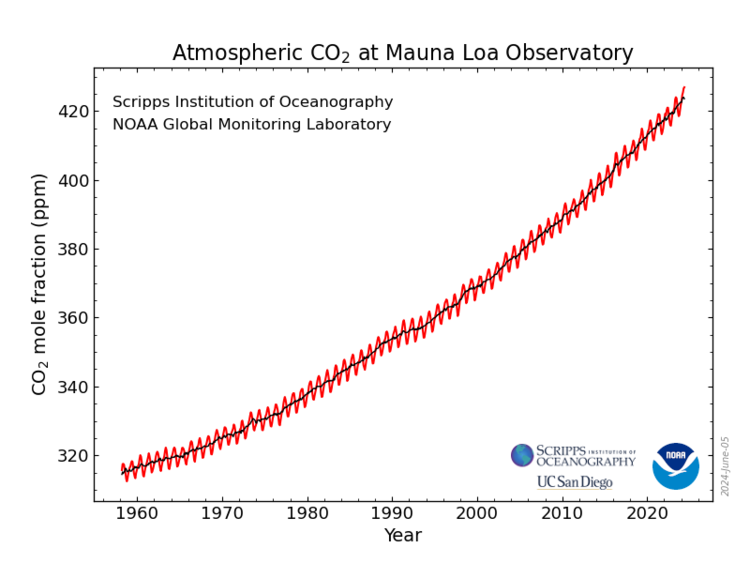

That is worrisome since all human civilization developed under cooler conditions during which the parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere tended to be around 280. By pumping billions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually, our industrial civilization has raised that average to 426 ppm.

That concentration of CO2 was typical of the Middle Pliocene, roughly 3 million years ago, when it was hotter in much of the earth and seas were somewhat higher. See Michael E. Mann’s magisterial Our Fragile Moment, which I discussed with him here.

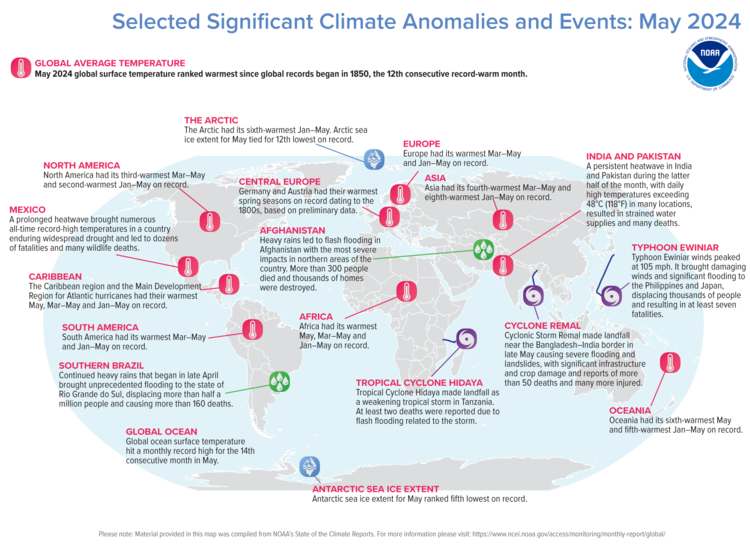

While the average of earth temperatures was higher in May than ever before recorded, some places got hit worse than others. India and Pakistan saw unbearable heat waves. New Delhi, India’s capital, may have hit 49 degrees C. (122F.), and a glitch in the records caused a panic when it was misread as 52° C. (125.6° F.). Still, 48°C or 49°C was plenty hot enough to cause heat stroke and kill off dozens of people. Mexico likewise had a massive heat wave that killed some people. And Africa was deadly hot, with hot waters off Tanzania contributing to a typhoon that caused flash floods. In fact there were 5 named typhoons, an above-average number. And arctic sea ice was low, though not the lowest it has been.

NOAA’s infographic explains:

The past 14 months have been so hot because an El Nino has been layered over climbing temperatures because of climate change. In El Nina years strong trade winds blow from Indonesia where the water is colder east to the coast of Latin America, bringing up colder water even in the usually warmer east, which has a cooling effect. In El Nino years those trade winds are weakened and warm water off the Latin American Coast creates a pressure system that has a heating effect.

But even with a hotter El Nino year, the records wouldn’t have been broken on this scale. El Ninos break out every few years– it is a cycle and we’ve seen them before. But we haven’t seen these temperatures before. They haven’t been seen since our ancestors were making bone tools in Morocco 120,000 years ago.

Although some pundits have said the earth has already exceeded the 1.5° C. (2.7°F) of extra warming above pre-industrial levels that the Paris Climate accord of 2015 pledged to avoid, this is not true. There is a difference between occasional spikes of global temperature and reaching a new average plateau. At current rates of burning fossil fuels we won’t race past the 1.5° C. limit as a global average temperature increase until about 2033. Scientists worry that breaching this limit will throw the global climate system into chaos that will pose challenges to keeping civilization going.

At the moment, Professor Mann says we have reduced the rate of increase in emissions so much that we are no longer headed for a 4° C. increase but rather toward a 3° C. increase. That is still way too much. We need to spend the next ten years significantly cutting back on our use of fossil fuels by switching to wind, solar, water and battery for electricity and to electric vehicles for transportation. The smaller the final temperature increase, the fewer catastrophes our children and grandchildren will have to deal with. Plus, moving to green energy quickly will save you money.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved