By Karrin Vasby Anderson, Colorado State University | –

(The Conversation) – After a jury convicted Donald Trump of 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up a politically damaging relationship, he responded by warning viewers of his post-verdict news conference: “If they can do this to me, they can do this to anyone.”

That statement simultaneously invokes the ideal of an independent judiciary and attempts to delegitimize it.

As a scholar of political communication, I study how rhetoric strengthens or erodes democratic institutions and can prime an audience to expect or accept violence. Regardless of how someone feels about the legal arguments made during Trump’s trial, Trump’s attempts to prevail in the court of public opinion continue his campaign to discredit democratic institutions and threaten anyone who gets in his way.

Demagoguery is weaponized political communication that, as communication scholar Jennifer Mercieca explains, “undermines both democratic decision-making and democracy itself.” Demagogues use rhetoric to dominate an electorate rather than to persuade voters. Key characteristics include evading responsibility for claims and scapegoating anyone disloyal to the demagogue.

Demagogic communication includes one or more of what scholars Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt identify as “key indicators of authoritarian behavior.” Those include rejection of, or weak commitment to, democratic rules and norms; denial of the legitimacy of political opponents; tolerance or encouragement of violence; and readiness to curtail civil liberties and media freedom.

In the aftermath of Trump’s felony conviction, the demagogic rhetoric of Trump and allied Republicans delegitimizeed democratic institutions and fostered threats of violence.

‘Designed to distract’

When Trump declared that “if they can do this to me, they can do this to anyone,” he was, of course, correct. Ideally, that’s how laws work. They should apply equally to a regular citizen and a former president.

Trump’s case is extraordinary given his status as a former president, and the legal theory used by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has been dubbed “novel.” Nonetheless, in the legal and national security publication Just Security, Siven Watt and Norman L. Eisen document a long history of state prosecutors going after politicians who flout laws to benefit political campaigns in similar ways.

Trump’s posts on social media were designed to distract from those facts by undermining the independence and trustworthiness of the judiciary and scapegoating anyone who isn’t a Trump supporter. That included President Joe Biden, officers of the court, immigrants and even a Fox News anchor deemed insufficiently supportive.

While the jury was deliberating, Trump set the stage, described the proceedings as a “Biden witch hunt,” the “WEAPONIZATION OF THE JUSTICE SYSTEM!” and “ELECTION INTERFERENCE.” Later he asserted that the gag order imposed by Judge Juan Merchan was “UNCONSTITUTIONAL” and described members of the “DOJ and White House” as “Thugs and Monsters who are destroying our Country.”

Immediately after the jury returned its verdict, Trump intensified his delegitimization of the American legal system, asserting that “the real verdict is going to be November 5 by the people” and adding, “our whole country is being rigged right now.”

Stoking fear

A particularly important dimension of Trump’s reaction to the verdict is that his comments combine the delegitimization of democratic institutions with ad hominem attacks – name-calling – and scapegoating. This strategy is textbook demagoguery.

The day after the judgment, Trump began his 33 minutes of public remarks with what seemed like a non sequitur, shifting from the case, to ad hominem attacks, to immigration, and back to ad hominem attacks:

“This is a case where if they can do this to me, they can do this to anyone. These are bad people. These are in many cases, I believe, sick people. When you look at our country what is happening, where millions of people are flowing in from all parts of the world – not just South America, from Africa, from Asia, from the Middle East – and they’re coming in from jails and prisons and they’re coming in from mental institutions and insane asylums. They are coming in from all over the world into our country. And we have a president and a group of fascists that don’t want to do anything about it. Because they could, right now, today. They could stop it, but he’s not. They’re destroying our country.”

Voters are encouraged to believe that the government — comprised of “sick people” and “fascists” — is after them, as are immigrants.

Although Trump’s jumbled approach makes his rhetoric sound disjointed — even chaotic — it’s carefully designed to stoke fear and create an atmosphere more amenable to an anti-democratic strongman. Trump’s jaunty 2016 campaign promise, “I alone can fix it,” and his more recent, ostensible “joke” about being “dictator for one day,” have given way to dire pronouncements from Trump about his fellow citizens, such as this late-2023 statement: “The threat from outside forces is far less sinister, dangerous and grave than the threat from within. Our threat is from within.”

The strategy would be less effective if Trump was the only one deploying it. But, following a familiar pattern, prominent Republicans reliably echoed his framing.

The Associated Press reported that the “ferocity of the outcry was remarkable, tossing aside usual restraints that lawmakers and political figures have observed in the past when refraining from criticism of judges and juries.”

The Guardian summarized Republicans’ responses: “A shameful day in American History. A sham show trial. A kangaroo court. A total witch-hunt. Worthy of a banana republic. These were the reactions from senior elected Republicans, who once claimed the mantle of the party of law and order, to the news that Donald Trump had become the first former US president convicted of a crime.”

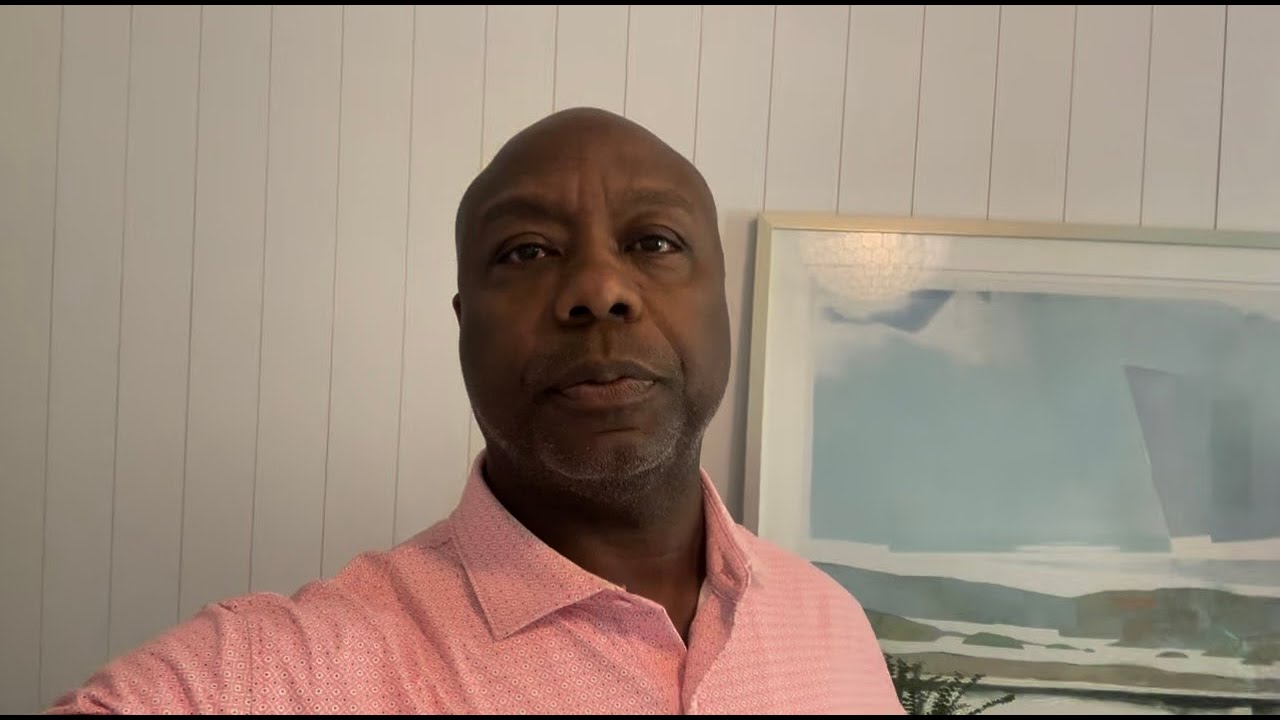

Republican senator and vice-presidential hopeful Tim Scott’s impassioned attack on the judiciary was emblematic of the response. He called the verdict a “hoax,” a “sham” and an “absolute injustice justice system.” He then addressed Bragg, the Manhatten district attorney, directly, saying, “DA Bragg, hear me clearly: You cannot silence the American people. You cannot stop us from voting for change.”

‘Hang everyone’

Stoking fear through ad hominem attacks and scapegoating is often a precursor to violence. The Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol followed Trump’s complaints about a “rigged” election.

NBC News reported that in the aftermath of Trump complaining about a “rigged” jury trial, posts are circulating on social media that target trial Judge Merchan, Bragg and the jurors with doxxing, intimidation and even death threats.

NBC quoted one poster who said, “We need to identify each juror. Then make them miserable. Maybe even suicidal.” Reuters quoted Patriots.win users who said, “1,000,000 men (armed) need to go to Washington and hang everyone. That’s the only solution” and “Trump should already know he has an army willing to fight and die for him if he says the words. … I’ll take up arms if he asks.”

Not everyone who supports Trump politically is poised to “take up arms,” but video posted on X by Donald Trump Jr. with the tagline “F— JOE BIDEN” shows an arena full of fans awaiting the UFC lightweight championship chanting “F— Joe Biden” and cheering Trump as he smiles and raises his fist.

Video of the event was posted on YouTube and circulated by right-wing websites like the Daily Caller and Breitbart.

In her book “Demagoguery and Democracy,” communication scholar Patricia Roberts-Miller explains that “We don’t have demagoguery in our culture because a demagogue came to power; when demagoguery becomes the normal way of participating in public discourse, then it’s just a question of time until a demagogue arises.”

A demagogue has arisen.

Karrin Vasby Anderson, Professor of Communication Studies, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved